Overview

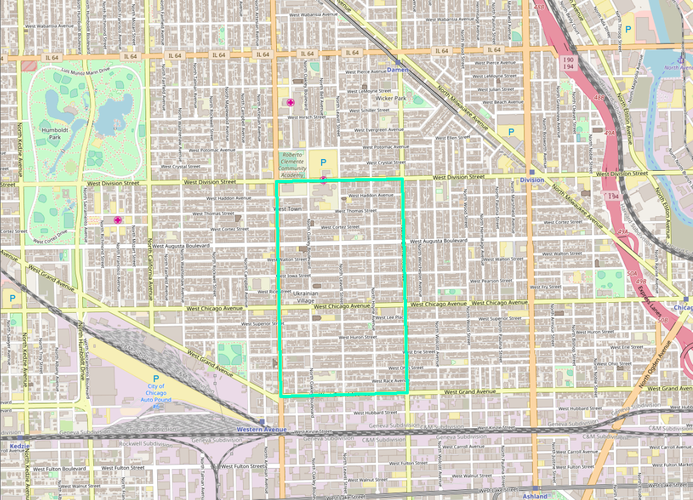

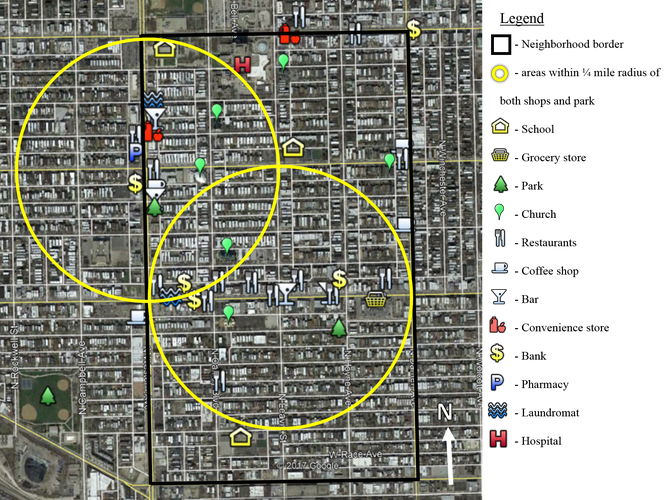

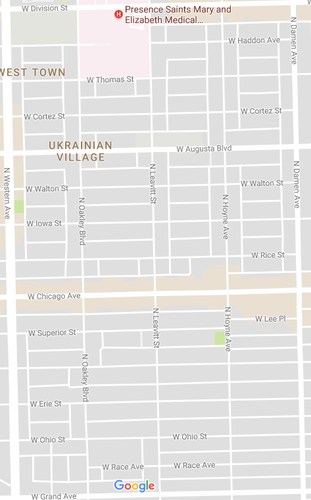

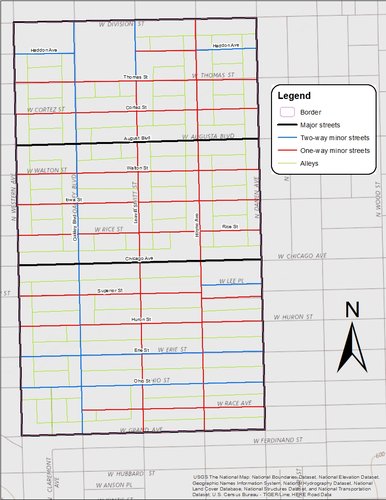

As seen in the aboveimage, Ukrainian Village is bounded by W. Division Street on the North, N. Damen Avenue on the East, W. Grand Avenue on the South, and W. Western Avenue on the West, with a total area of approximately 0.43 square miles according to Google Earth. Though the neighborhood's location in four different census tracts (2424, 2423, 2430, and 2429) made estimating population somewhat more difficult, it has about 10,000 denizens, according to Social Explorer. The neighborhood's rectangular shape and central commercial district on Chicago Avenue makes for an easy walk to most places one would need to go, but in both population and geographic size it is the size of 2-3 of Perry's neighborhoods.

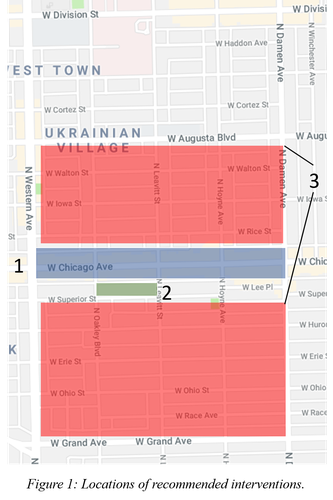

Ukrainian Village’s identity unsurprisingly reflects the area’s Ukrainian population, the neighborhood’s namesake. Along Chicago Ave., the neighborhood’s main commercial thoroughfare, a number of the storefronts have signage in both English and Ukrainian, as well as fliers advertising local events (such as the Ukrainian Fashion Festival and numerous events whose Ukrainian title I could not decipher) taped up in the windows (Figure 1). The Ukrainian influence is also evident in the frequent usage of blue and yellow, the colors of the Ukrainian flag, as well as the Ukrainian National State Emblem (Figure 2). Public signage further reinforce the identity of the neighborhood: banners on both sides of Chicago Avenue mark the street as Ukrainian Village, as do signs on Leavitt St.

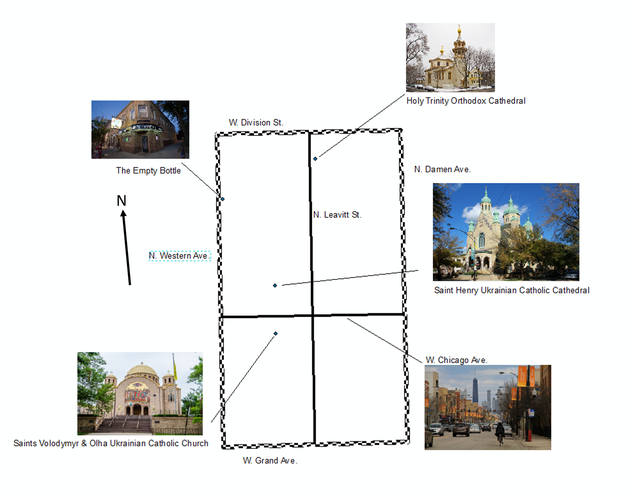

Beyond window dressing, a number of the shops cater to and reflect the neighborhood’s Ukrainian community. A number of Ukrainian restaurants can be found on Chicago Avenue, and scattered throughout the neighborhood are two Ukrainian Catholic churches (not including the Ukrainian Catholic Eparchy) and one Ukrainian Orthodox cathedral, as well as the Ukrainian National Museum, the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art, and the Ukrainian Cultural Center. These churches’ architectural styling further reflects the Eastern European origin of their founders and congregations (Figure 3). All of these elements are centered on Chicago Avenue, but they extend both northwards and southwards, and it is for this reason that I chose to define Ukrainian Village as extending south to Grand Avenue; though about half of the online sources I found defined the neighborhood as terminating at Chicago Avenue, a number of Ukrainian signs and institutions are found between Chicago and Grand, as is Fiore’s Delicatessen, which proudly proclaims itself to be in Ukrainian Village.

Even given the neighborhood’s relative boundedness as an area of Ukrainian residence and culture, there is evidence of influence from the neighborhoods to the North and East, namely Wicker Park and East Village, both of which are rapidly gentrifying. This comes primarily in the form of newer condominium buildings, which stand in stark contrast to the brownstones (both walk-up apartment buildings and free-standing homes or townhouses) and bungalows which are otherwise architecturally dominant in the neighborhood (Figures 4 and 5). Despite the new money creeping in from the edges, the neighborhood retains a feeling distinct from those of its neighbors, not only because of the Ukrainian accoutrements but also because of the distinctly middle-class shops and residences, which differ markedly from the newer, more bourgeois chain shops (such as Mariano’s and WHISK, a brunch restaurant [Figure 6]) found on Chicago Avenue towards the eastern edge of the neighborhood, as well as from the used car lots and warehouses to the south and west of the neighborhood core.

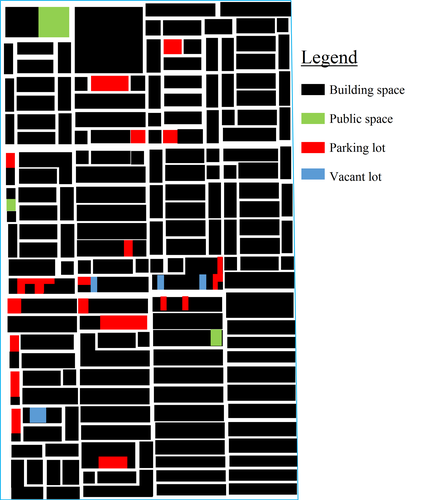

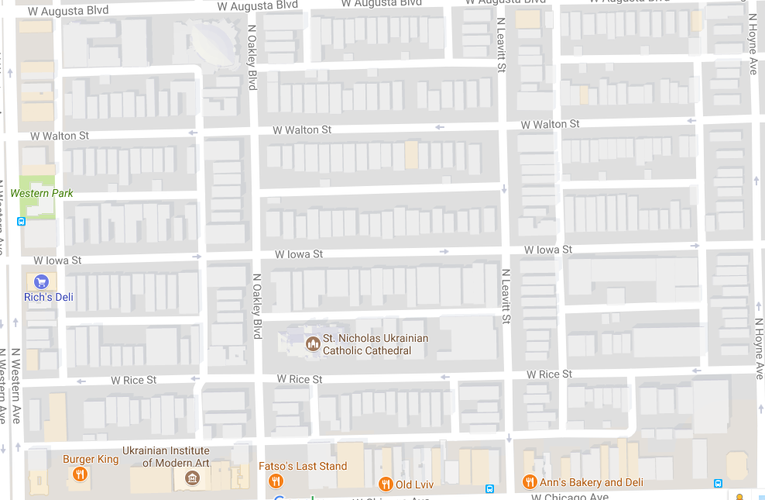

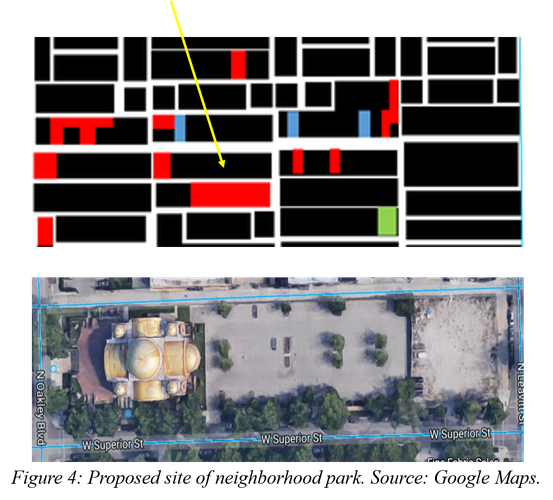

Though these newer condominiums may pose a danger to the social unity and identity, I actually found that the neighborhood remained architecturally coherent in spite of the intermingled new and old styles (if one can stomach the looks of some of the more tastelessly designed newer condominium buildings). In my opinion, the design of the neighborhood is far more threatened by the encroachment of single-story buildings set back behind empty and needlessly large parking lots, such as the Burger King on the west side of the district and its accompanying asphalt oasis, or Fatso’s Last Stand, which is more unfortunately placed in the heart of the neighborhood’s downtown but is at least locally owned. Thankfully, however, the new developer modernist condominium buildings and anti-urban drive-thru restaurants have not yet succeeded in making the neighborhood anything less than pleasant and easy to walk around.

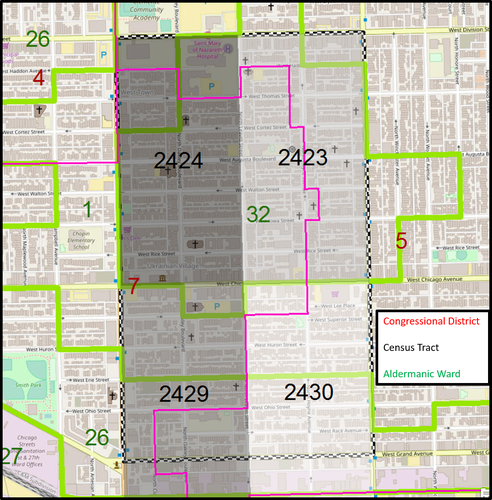

As seen in the above map, there are a number of overlapping delineations that include Ukrainian Village (enclosed by the black-and-white checkered line). The neighborhood is in: both the 7th and 5th Illinois Congressional Districts (labeled in red and shown by the pink line on the map); four different census tracts (2424, 2423, 2430, and 2429, shown in grayscale and labeled in black on the map); and three different aldermanic wards (the 1st, 32nd, and 26th, shown and labeled in green on the map). In addition, Ukrainian Village is wholly within the 13th Chicago Police District, the West Town community area, and the Vicariate III-B parish.

Ukrainian Village was initially settled by German immigrants in the years following the 1871 Chicago fire, but were quickly outnumbered by working-class Russian and Ukrainian immigrants who began settling in the area in the 1880s. Though the neighborhood had previously been farmland, it became more densely developed with the 1895 construction of the Paulina Connector, an elevated train line that ran along Paulina St. and linked the Blue and Pink lines until its decommissioning in 1964. At this same time around the turn of the century, many of the residents became employed building the large mansions in Wicker Park, the neighborhood’s wealthier neighborhood to the North. A second wave of immigration came in the 1910s as people fled political repression at home in Ukraine, and a third following World War II brought highly educated professionals (lawyers, doctors, writers, artists).

With this third period of immigration, a number of neighborhood institutions arose, allowing the Ukrainian community to become largely self-sufficient. These institutions included not only the neighborhood’s three Ukrainian churches, but the SelfReliance Ukrainian American Federal Credit Union and cultural centers such as the Ukrainian National Museum and the Ukrainian Institute of Modern Art. The growth of these and other neighborhood institutions helped Ukrainian Village become solidly middle-class despite its location adjacent to industrial areas and areas affected by poverty and crime; today, median household income is about $70,000. The fourth and most recent wave of Ukrainian immigration came in the 1990s following the dissolution of the Soviet Union. While it is unclear to what degree the layout of the neighborhood was planned by the city, it is evident that the strong neighborhood ties and sense of community had a significant impact on the development of the neighborhood as a place to work and live. That Ukrainian Village was the first to be formally designated as a neighborhood by the city when Jane Byrne did so in 1983 is perhaps a testament to its strong community ties and self-sufficiency with regards to cultural institutions and the other essentials of daily life, despite its relative lack of a neighborhood center or focal point as in areas like Lincoln Square. (This lack of focal point or central public space may indicate that the area was not highly planned by the city.)

In addition to helping the neighborhood remain middle-class during Chicago’s industrialization and subsequent socioeconomic changes, Ukrainian Village’s strong ethnic institutions may have also played a role – in conjunction with the neighborhood’s lack of direct rail transit – in slowing, though not entirely preventing, gentrification in the neighborhood. As mentioned in the “Identity” section, there is visible evidence of new money being poured into Ukrainian Village by developers, most notably in the boxy new condominium buildings on Chicago Avenue and throughout the rest of the neighborhood. A number of real estate companies and magazines have labeled Ukrainian Village one of the hottest neighborhoods in Chicago and the country. However, community advocacy (formalized in the Ukrainian Village Neighborhood Association, or UVNA) is working to stem the tide and influence of yuppies: the UVNA has succeeded in acquiring historical landmark designation for 75% of the neighborhood, preventing demolition of many of the neighborhood’s older buildings, and works to maintain the neighborhood’s identity by involving even non-Ukrainian immigrants in Ukrainian cultural activities. It remains to be seen whether the Ukrainian Village will retain its identity in the face of new arrivals or if its name will become the only vestige of its history as in many other Chicago neighborhoods.

“About Empty Bottle.” Empty Bottle (blog). Accessed October 17, 2017. http://emptybottle.com/about/.

“Chicago’s Holy Trinity Cathedral to Celebrate Feast of Saint John of Chicago.” Accessed October 17, 2017. http://domoca.org/news_121016_1.html.

Cook_County_GIS. “Congressional District.” Accessed October 16, 2017. Cook County Geographic Information Systems, 18 September 2017. Accessed through ArcGIS Online.

Massimo_slamwrote, 2013-04-22 13:13:00 Massimo_slam Massimo_slam 2013-04-22 13:13:00. “Ukrainian Village, Chicago.” Accessed October 17, 2017. https://massimo-slam.livejournal.com/12991.html.

Rcapacciodev. “Wards.” Accessed October 16, 2017. Published April 14, 2014. Accessed through ArcGIS Online.

“Ukrainian Village.” Accessed October 16, 2017. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/2160.html.

“Ukrainian Village: St. Nicholas Ukrainian Greek Catholic Cathedral.” Accessed October 17, 2017. http://www.publicartinchicago.com/ukrainian-village-st-nicholas-ukrainian-greek-catholic-cathedral/.

“Ukrainian Village: Traditions Overcome ‘Hottest Neighborhood’ Label.” Chicagoly Magazine (blog). Accessed October 16, 2017. https://chicagolymag.com/web/2017/03/ukrainian-village-traditions-overcome-hottest-neighborhood-label/

https://chicagolymag.com/web/2017/03/ukrainian-village-traditions-overcome-hottest-neighborhood-label/

.

“US Demography 1790 to Present (HTML5).” Social Explorer. Accessed October 17, 2017. https://www.socialexplorer.com/a9676d974c/explore.

“Sts. Volodymyr & Olha Ukrainian Catholic Church.” Open House Chicago. Accessed October 17, 2017. https://openhousechicago.org/sites/site/sts-volodymyr-olha-ukrainian-catholic-church/.

Social Mix

As perhaps evidenced by the above tables, Ukrainian Village is not terribly diverse. While the neighborhood is comparably diverse to West Town, the West Region of Chicago, and the City of Chicago in terms of nativity and place of origin of foreign-born citizens, the neighborhood is still much more white overall (81%!) than the city as a whole. This is perhaps in part because the majority of immigrants to the neighborhood are European or Mexican, whereas the city of Chicago receives many immigrants from Asian countries. (One interesting and related fact I discovered is that significantly more recent immigrants are from Romania than Ukraine, despite the neighborhood’s name.)

Nor is Ukrainian Village remarkably diverse in terms of occupation or age, most likely reflecting the recent influx of young professionals. (See, for instance, the fact that 47% of residents are between 18 and 35 years old, and that 55.5% of working residents work in either “Management, Business, and Financial Operations Occupations” or in “Professional or Related Occupations.”) This large body of young professionals is also most likely responsible for the neighborhood’s relatively greater diversity (compared to the region and city) in terms of mode of commute: young people are less likely to drive to work, and more likely to take public transit, ride a bike, or simply live in areas where they can walk to work. (While multimodality is admittedly an unorthodox measure of diversity, I would argue that it is still an important measure of the degree to which a given neighborhood can attract and accommodate multiple habits and modes of living.)