Overview

Identity

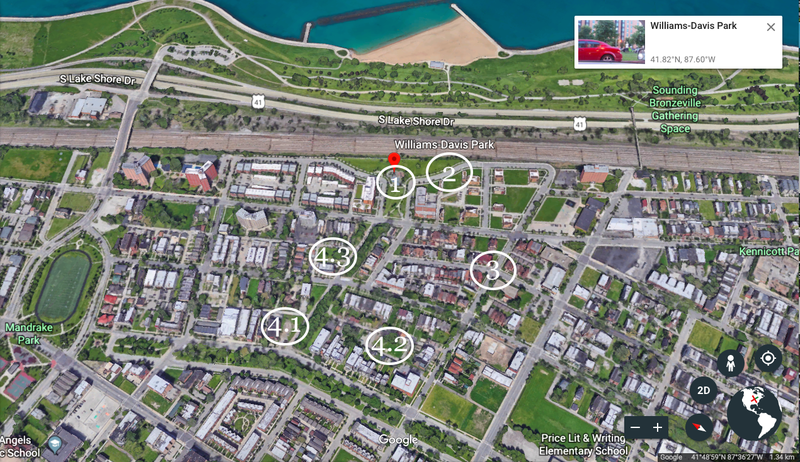

Being a primarily residential area with small commercial establishments spread throughout its borders, it is difficult for a non-resident to construct an accurate sense of Oakland’s identity. Upon arriving in the neighborhood, at Williams-Davis Park, I was greeted by a “lumpy bronze figure called Restoration” (Dukmasova). On it were the following words: "This sculpture is dedicated to the men and women who remained in the Oakland community during difficult times and worked hard to restore its former beauty" (see first picture below). I was not able to deduce the magnitude of this transformation from simply reading this message. However, a thorough historical investigation conducted after the fact was helpful in beginning to understand the nature of the cited change.

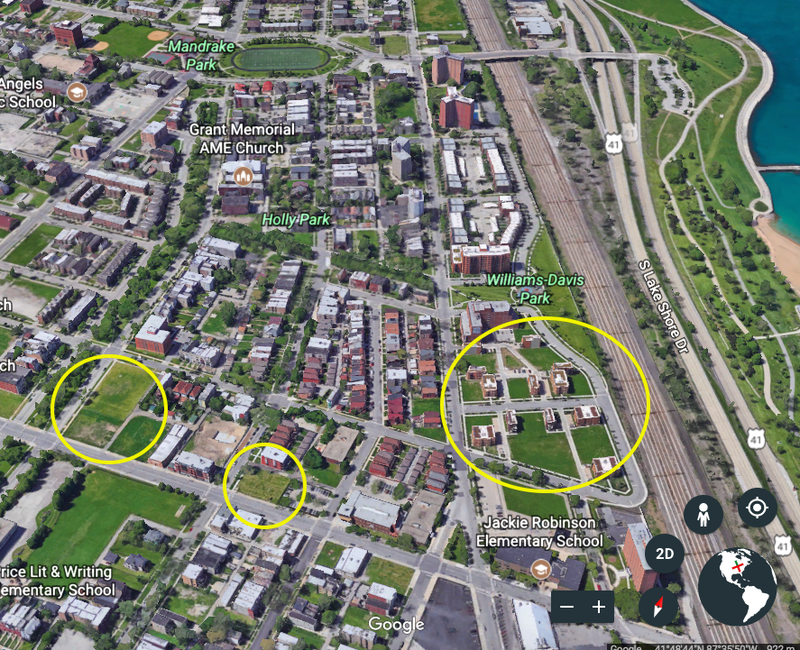

To begin to illustrate this change, this discussion will employ the use of a local case study. The 4100 block of South Berkeley Avenue in Oakland, just around the corner from the aforementioned park, plays host to a row of architecturally significant homes that were originally built for the neighborhood’s wealthiest residents in the late 1800’s (Dukmasova). As will be discussed in the last section of this assignment, the neighborhood later fell upon hard times, to the extent that by 1990, it had the “lowest family income and highest unemployment percentage” in the City of Chicago (Grossman). While it did so, “[nearby public housing complexes] lapsed into neglect and disrepair, [causing] Berkeley Avenue [to also deteriorate] in their shadow (Dukmasova). However, and this is where the sculpture’s message becomes relevant, “within a decade black homeowners' [specifically those that did not flee from the region] investment in the [South Berkeley Avenue homes] began to pay off as the projects were redeveloped into low-density mixed-income housing” (Dukmasova).

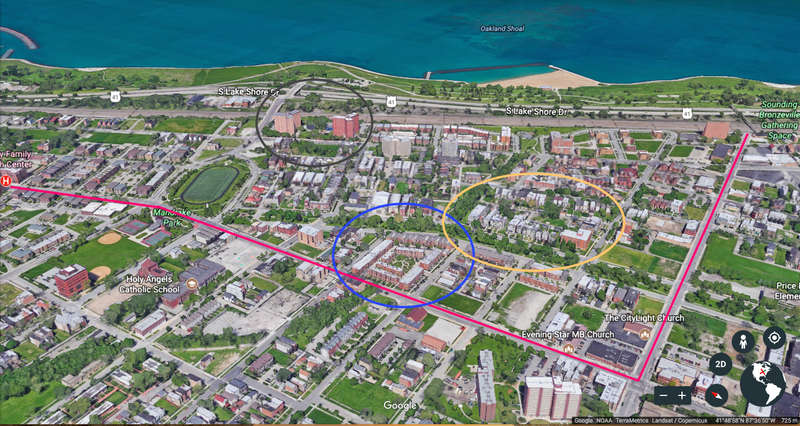

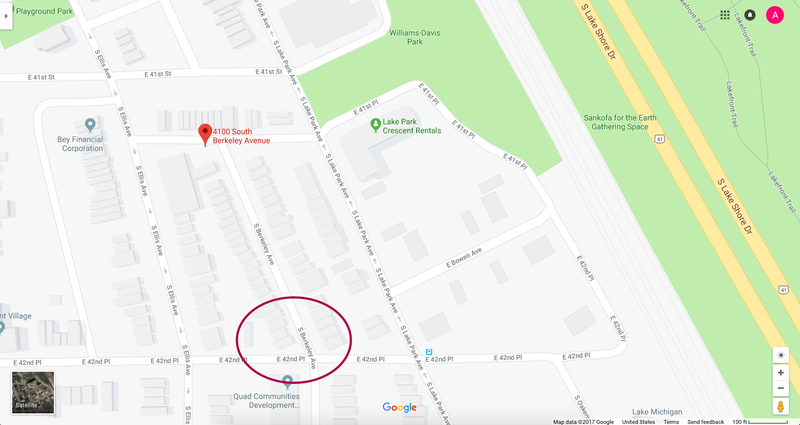

While it was not always a growing neighborhood, Oakland is currently the site of numerous new development projects, many of which are capitalizing on the area’s attractive attributes, including proximity to Lake Michigan and views of downtown (Grossman). Walking past these developments, namely the luxury condos under construction on South Ellis Avenue and East 42nd Place (see second picture below), illustrated for me the nature of the change mentioned on the sculpture. Resilience in this context is not unique to Oakland, since North Kenwood also experienced a similar deterioration and rebound. Those that currently inhabited the neighborhood, and those who did so during the turmoil, do share one unifying attribute: a commitment to the conservation of Oakland.

Works Cited

Dukmasova, Maya. "A Block in Oakland Is an Oasis, and a Tale of Segregation." Chicago Reader. Chicago Reader, 15 Oct. 2017. Web.

Grossman, Ron, and Charles Leroux. "The Unmaking of a Ghetto." Tribunedigital-chicagotribune. N.p., 29 Jan. 2006. Web.

Tolson, Claudette. "Oakland." Encyclopedia of Chicago. N.p., n.d. Web.

Size

Per Google, the size of Oakland is 383 acres. Per Social Explorer, Oakland houses around 4,878 people.

Very evenly spread out, in term of housing density, with few anomalies.

Pictures

As mentioned above, the sculpture that was commemorated as a symbol of the neighborhood's rebirth.

New, mid-density developments in Oakland, many of which have been pre-sold.

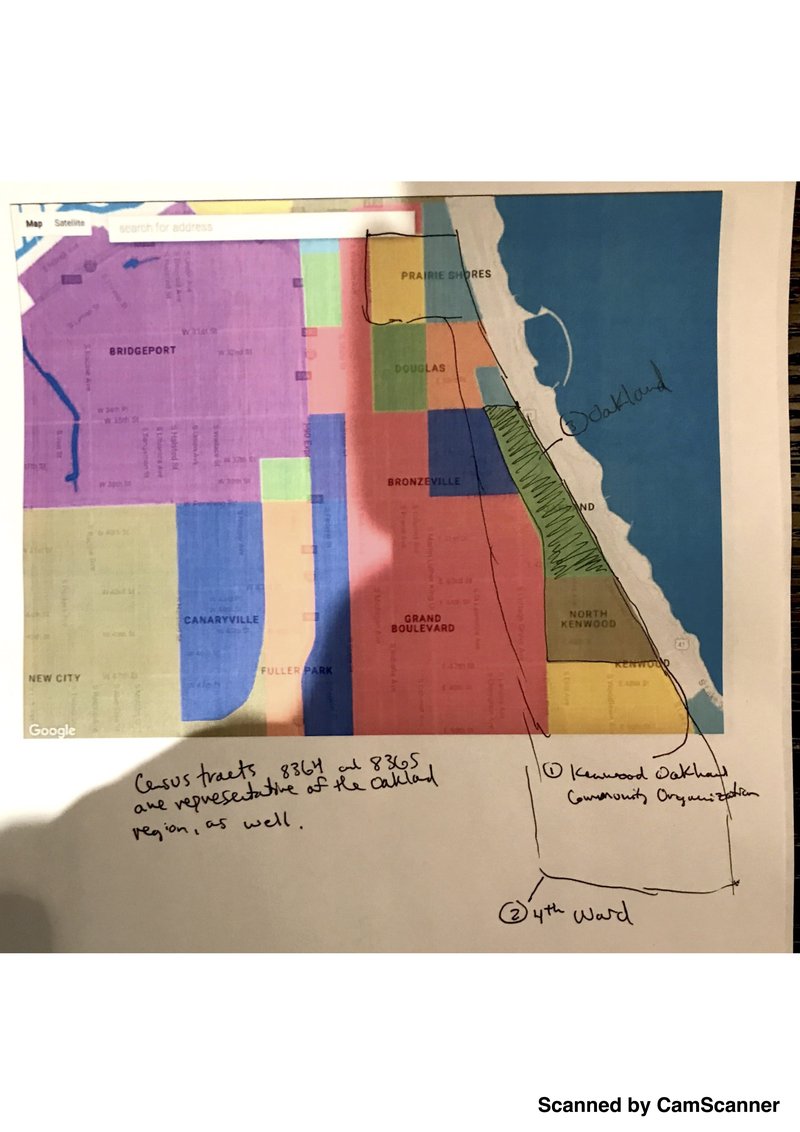

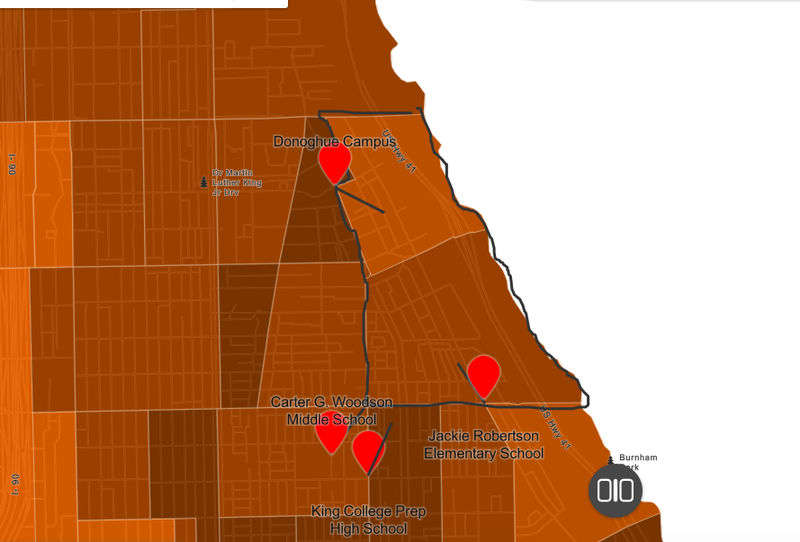

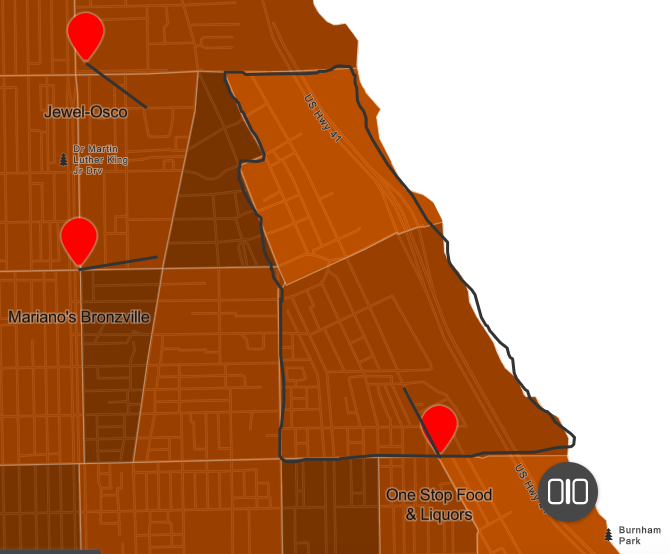

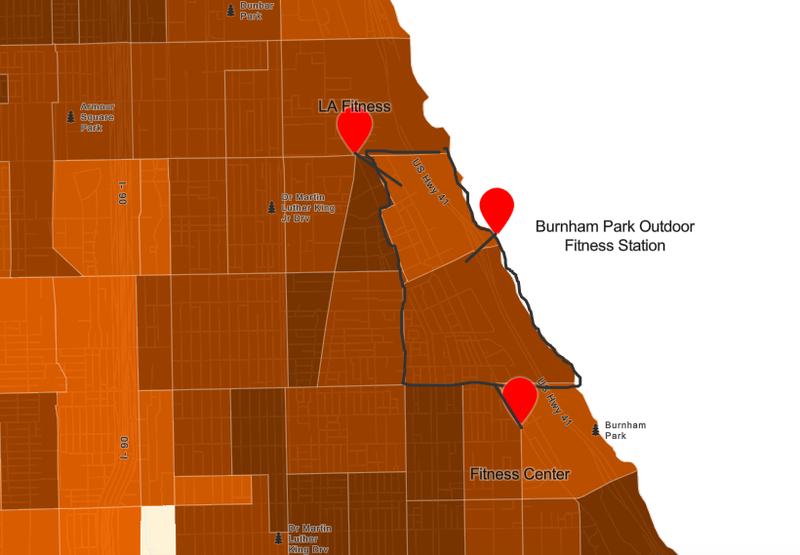

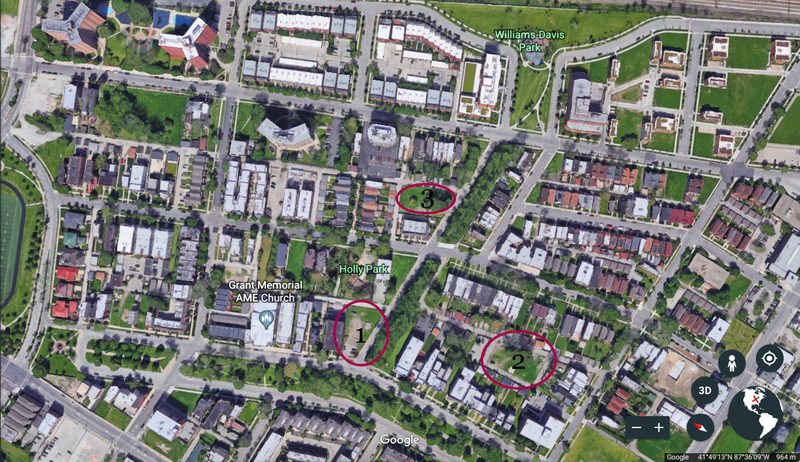

Above is a graphic denoting some of the layers of the community.

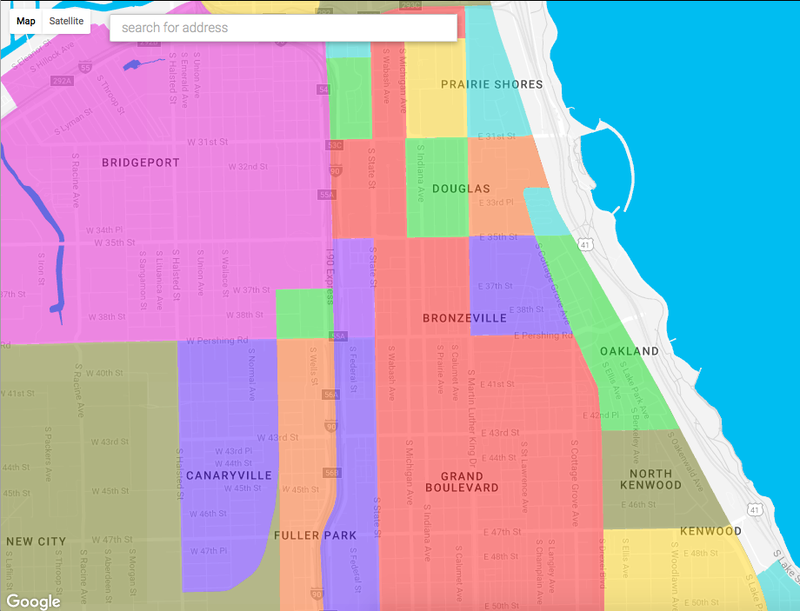

Above are officially recognized delineations for the Oakland neighborhood.

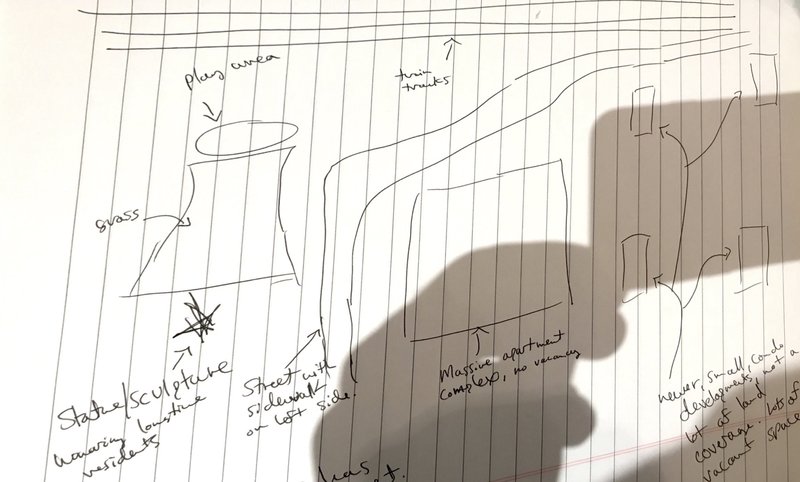

Diagram

History

This overview will begin by describing the initial organization of the neighborhood. In 1851, Charles Cleaver bought 22 acres of land in the heart of the neighborhood’s modern day boundaries, and developed both a soap factory and a company town, the latter of which held worker housing, a commissary, a house of worship, and a town hall (Tolson). The region’s popularity amongst residents was grounded in “nearby Camp Douglas, the stockyards, and a commercial district that included popular saloons” (Tolson). In 1867, transportation via a horse car line was introduced (later followed by an even faster cable car), increasing the region’s accessibility to downtown (Tolson, Grossman).

While the neighborhood housed the upper echelons of society in the 1870’s, in homes “faced with stone and graced by the handiwork of artisans in marble, stained glass and copper,” its primary demographic shifted towards working-class immigrants as the 1900’s approached (Tolson, Grossman). The demographic would shift once again as time passed. In the first half of the 20th century, “African-Americans escaping overcrowded ghettos north and west…moved into rented apartments in once-stately homes [in Oakland and the surrounding area] that had been converted” (Grossman). In the second half, “more than 98 percent of Oakland had become poor and black, with people living in converted apartments, kitchenettes, crowded slum dwellings and public housing projects” (Grossman). By 1990, the neighborhood had the “lowest family income, highest unemployment percentage, [and] most families living below the poverty line” in the City of Chicago (Grossman).

To better understand this progression, its necessary to touch on the role of the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) in the community. In the 1950’s, in reaction to the expansion of south side Chicago’s African American ghetto, “authorities turned to public housing as a way to keep blacks confined to black neighborhoods” (Grossman). The CHA’s lax screening standards led to these projects becoming “huge reservoirs of impoverished, broken families” (Grossman). In the late 1900’s, these projects were eventually demolished, because the responsible parties “increasingly saw these projects not as a solution to endemic property, but an institutionalization of it” (Grossman). This eventually led to their advocacy of mixed income housing as a replacement for the former residents of these projects (Grossman). Given that these projects had “closed off North Oakland/Kenwood on three sides,” their demolition revealed “an unlikely combination of elegant old homes and weed-choked empty lots,” bordering Lake Michigan, and privy to “dramatic views of the downtown skyline” (Grossman). These are attractive attributes that have likely driven the “galloping development and skyrocketing property values” that have come to characterize Oakland and its surrounding neighborhoods (Grossman).

Works Cited

Grossman, Ron, and Charles Leroux. "The Unmaking of a Ghetto." Tribunedigital-chicagotribune. N.p., 29 Jan. 2006. Web.

Tolson, Claudette. "Oakland." Encyclopedia of Chicago. N.p., n.d. Web.

Social Mix

Assignment 2

The neighborhood of Oakland hosts very little racial diversity at the level of statistical precision. Specifically, Oakland's Simpson Diversity Index value (when calculated using the races of Non-Hispanic Black of African America, Non-Hispanic White, and Hispanic) rests at 1.16 for the year of 2016, per information compiled by Social Explorer. Per the same source, over 88% of the region’s population is “Non-Hispanic Black or African American.” The remaining 12% or so are White, Asian, Hispanic, or of another race. In comparison, the City of Chicago, boasts an index value of 2.99 when calculated across the same three races, demonstrating a near even presence of these three races within this larger geographic region.

Having discussed racial diversity, this analysis can now proceed to exploring income diversity in the region. This can be taken from income statistics, or deduced from the distribution of housing values. While there are household incomes ranging from less than $10,000 to more than $200,000, the median household income is $30,777, implying that a large percentage of these households are located towards the lower band of this range. Housing values for owner occupied units were largely in the $150,000-$300,000 range, though individuals in the lower income bands previously mentioned are typically not in the pool of home buyers, so this value must be taken with a grain of salt.

Please see below for tables of supporting data, obtained from Social Explorer.