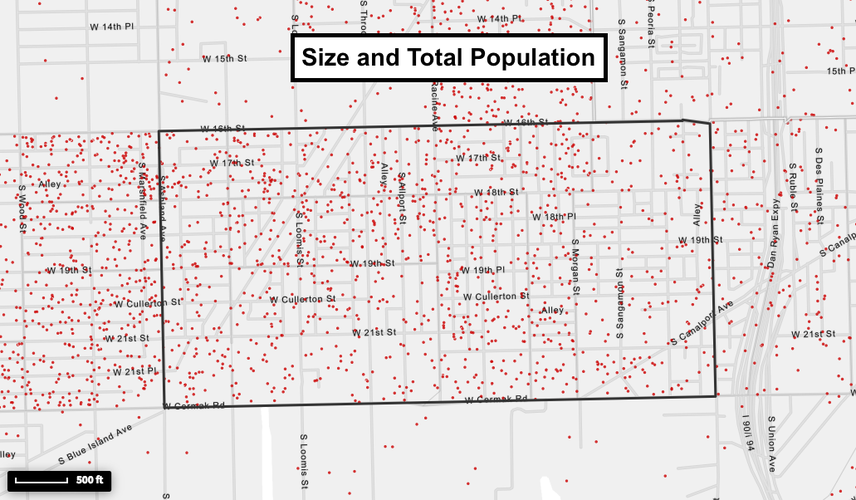

Overview

Pilsen has a total population of 11,140 people, according to 2016 survey data, and encompasses an area of 337 acres. Each dot on this map from Social Explorer represents 25 people.

Identity

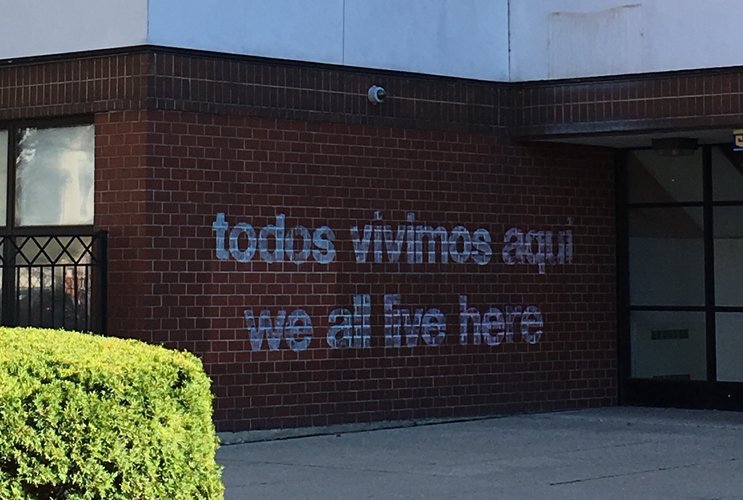

Pilsen, a predominantly Mexican neighborhood, has a strong sense of identity. From the moment one steps off the bus at 18th and Ashland, murals and banners sporting the Mexican flag set the scene. One of the first establishments east of the stop is Taquería Los Comales, advertising Mexican cuisine under a green, red, and white sign. One block east, Latin music emanates from a tamale restaurant, and the bookstore across the street advertises solely in Spanish.

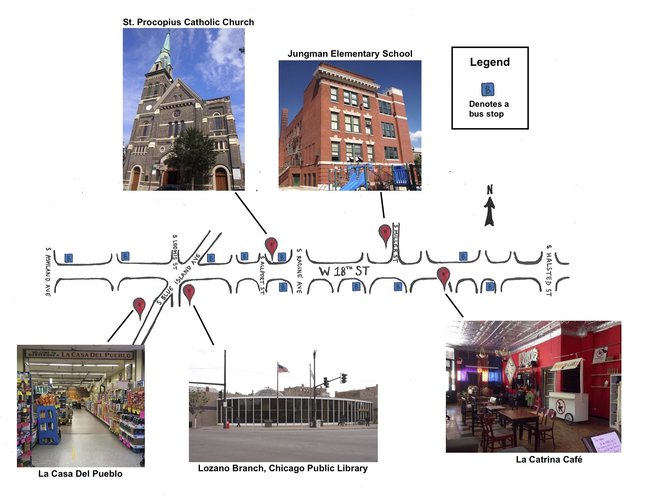

Off of 18th Street, Pilsen becomes sparser; away from this ribbon of commerce and culture, the neighborhood’s identity becomes markedly more discrete, relegated to a few other busy streets like South Blue Island Avenue. Here, the neighborhood’s Mexican heritage shines through in several distinct moments, most notably in La Casa Del Pueblo, Pilsen’s largest supermarket. Inside, one sees an array of fruits, vegetables, and spices that couldn’t be found in just any American supermarket: red and green jalapeños, habaneros, chiles, queso fresco, all boldly marked “Product of Mexico.” South Blue Island Avenue is lined with several of Pilsen’s most acclaimed and authentic Mexican restaurants, the Lozano Branch Public Library, and even a medical marijuana service. South Blue Island, however, is one of few instances of Pilsen culture south of 18th Street.

Away from the neighborhood’s periphery, the neighborhood is residential, and for blocks at time, a visiting pedestrian would have little to no indication that they were still in Pilsen. The architecture is somewhat cohesive, but in no way distinct from most Chicago neighborhoods or indicative of a particular culture. To combat this, some houses are adorned with red, green, and white banners. Corner groceries stores, too, restore a sense of identity in these otherwise unremarkable streets with their vibrant signage and Spanish adverts.

Additionally, Pilsen is a neighborhood of murals. Dispersed sporadically throughout the neighborhood, these huge, colorful gems serve no apparent purpose other than neighborhood unification and identification, much like the one I unexpectedly encountered across from Dvorak Park.

This, the westernmost edge of 18th street, feels like Pilsen at its most authentic; the prevalence of its Mexican influence dissipates gradually as one travels east into gentrified territory. Past South Allport Street, there is a notable shift from local lavanderías to sparkling new breweries and coffee shops. Situated throughout the newness are reminders that this is still Pilsen: A dress store for quinceañeras, a small Mexican art gallery, a smattering of corner groceries specializing in Mexican cuisine, and of course, the residents. In the midst of twenty-something-year-old newcomers and thrift shop-seeking tourists, families and friends who have called Pilsen home for decades cluster on the sidewalk or lounge on one another’s front steps. They chat about neighborhood happenings, like the open mic for women’s rights at La Catrina Café, or the community garden at St. Procopius Catholic Church. I approached one such group, and they told me about casual cookouts that turned into all-out block parties. These seasoned residents keep their doors open to one another, they entertain one another, they look out for one another, even if, as they say, newcomers don’t seem to appreciate their hospitality. Though old and new Pilseners coexist peacefully, the veteran residents acknowledge that gentrifiers don’t fit into the close-knit, family-friendly neighborhood environment that they have known for so long.

History

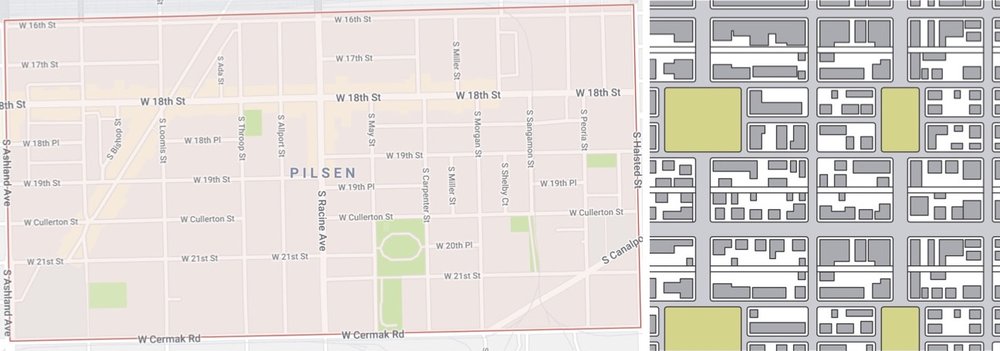

Since its founding in the 1840s, Pilsen has been shaped and defined by “both geography and human engineering” (Pero 10). At its conception, the German and Irish-settled neighborhood extended from the railroad tracks of 16th Street down to the Chicago River, from a cattle stockyard as its western border, eastward to Canal Street (Pero 11). Its prie location in between such a multitude of transportation modes – wagons, ships, trains, and cars – made the nascent Pilsen a commercial hub brimming with opportunity.

Lumber, beer, and textile were three particularly lucrative industries that brought Pilsen onto the public eye. In the 19th century, the Pilsen Yards were one of the largest, most prosperous lumber distributors worldwide. Brewers like the Atlas Brewing Company, the Pilsen Brewing Company, and the Peter Schoenhofen Company brought both wealth and public acclaim to Pilsen, and to this day remain known for their extraordinary success. Additionally, Pilsen industries showed their relative progressiveness by implementing policy that put women and other minorities to work at the textile assembly lines in the mid 1900s (Pero 12-15).

However, industrial success of this scale did not come without strife. A nationwide rail strike in 1877 (Gellman), spurred by repeated wage cuts, escalated into “one of the biggest street battles in U.S. labor history.” Due to the situation of a major railroad junction at the eastern edge of Pilsen, the worst of the violence, which took the lives of 30 immigrants and inflicted serious injury upon many others, took place at the intersection of 16th Street and Halsted (Pero 19).

The creation of so many unskilled jobs on railroads, lumber yards, and textile sweatshops in the 1870s brought about the influx of many Bohemian immigrants, who would go on to give Pilsen its name. One Bohemian settler gave his new restaurant the name “At the City of Plzn,” and the name subsequently caught on (Gellman).

However, the Czech heyday in Pilsen was somewhat short lived. In the 1920s, due labor shortages spurred by World War I, a significant population of Mexican immigrants first made their appearance in Pilsen, and have been a major presence ever since (Gellman). The Mexican population of Pilsen grew when immigration law and policy related to the expansion of the University of Illinois at Chicago in 1963 forced hundreds of Mexican families to relocate to the Lower West Side, south of 16th Street (Gellman). Once established, the Mexican immigrants created a “local economy that paralleled the dominant Chicago economy” (Pero 37). With their highly successful, albeit small, family business, the Mexican population thrived in Pilsen as other ethnic groups moved to different locations throughout Chicago.

Works Cited

Pero, Peter N. Chicago’s Pilsen Neighborhood. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Pub., 2011. Print.

Gellman, Erik. "Pilsen." Encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org. N. p., 2017. Web. 14 Oct. 2017.

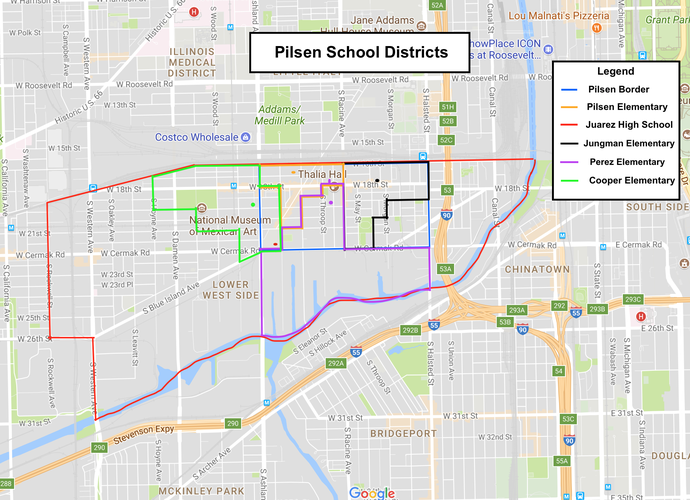

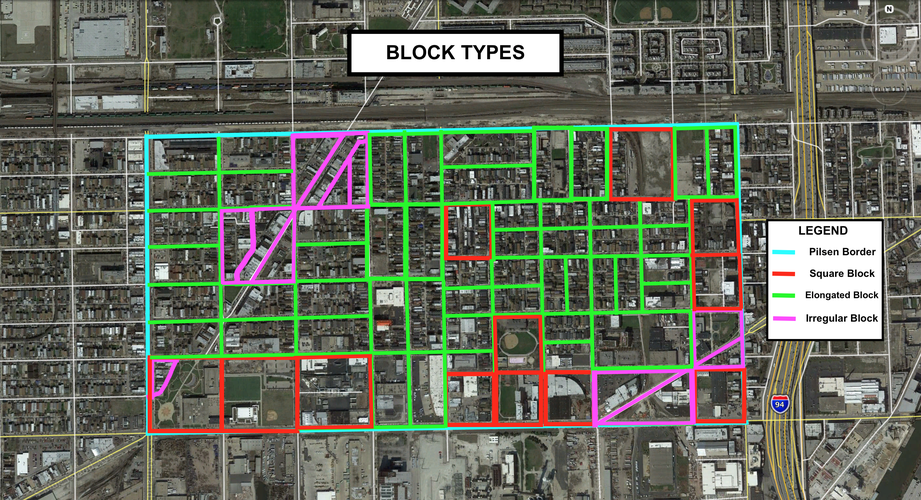

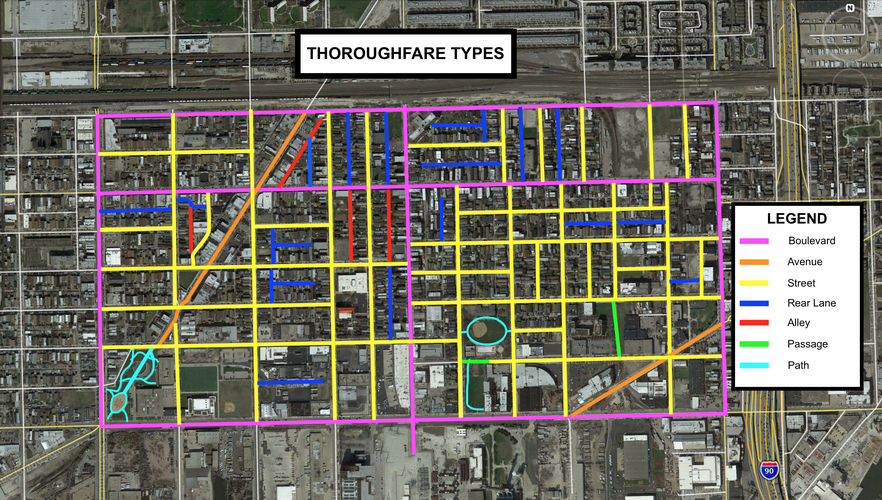

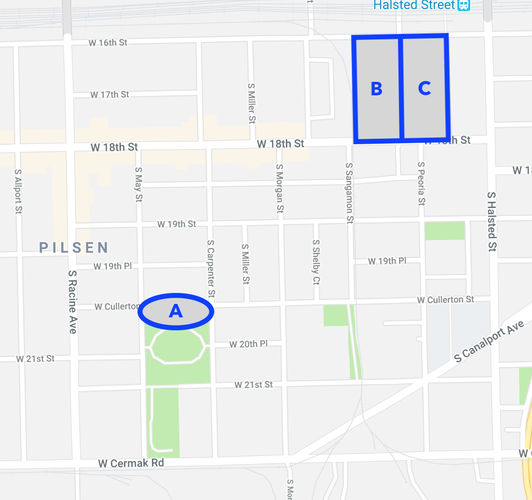

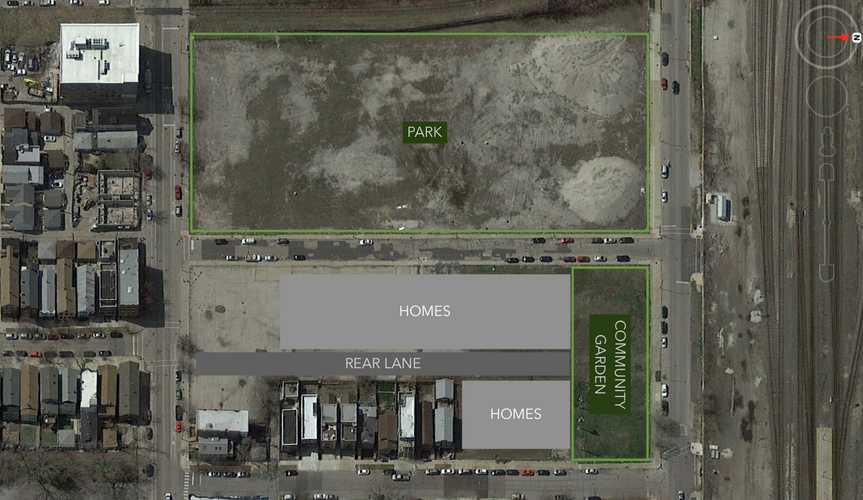

Diagram

Social Mix

The following tables display Pilsen's diversity in a variety of categories, compared with the calculated diversity of the Western region of Chicago and that of the City of Chicago as a whole. All data courtesy of Social Explorer.

Diversity Analysis

Given the generated data, I do not believe that Pilsen is a particularly diverse neighborhood. Its extremely high concentration of Hispanic or Latino residents, who constitute 72.6% of its total population, drastically outweigh the presence of other racial groups in the neighborhood. Particularly when compared with Chicago’s rather high racial diversity profile (3.47 out of 5 possible points), it is clear that Pilsen, which only earned a score of 1.78 out of 5, is relatively homogeneous when it comes to race. Additionally, we can see from the tables that housing values in Pilsen are greatly concentrated between $150,000 and $499,999. Well over half of all owner-occupied housing units, 62.4% to be exact, fall within this price range.

However, in terms of education, the neighborhood's most diverse category of the three that I chose, Pilsen exhibits a considerable equity between those who completed less than high school, those who completed high school or attained their GED, those who attended some college, and those who attained their Bachelor's degree. Very few residents attained a Master's or other advanced degree, but the drop-off here is comparable to drop-off that we see in the data for all of Chicago.

Despite this heterogeneous mixing of education levels, Pilsen still does not hold up to the diversity of the West Region or Chicago as a whole. Given these findings, it cannot be said that Pilsen is a truly diverse neighborhood, especially when compared with the socioeconomic and cultural cornucopia that is the city of Chicago.