Overview

The Coherence of Little Village

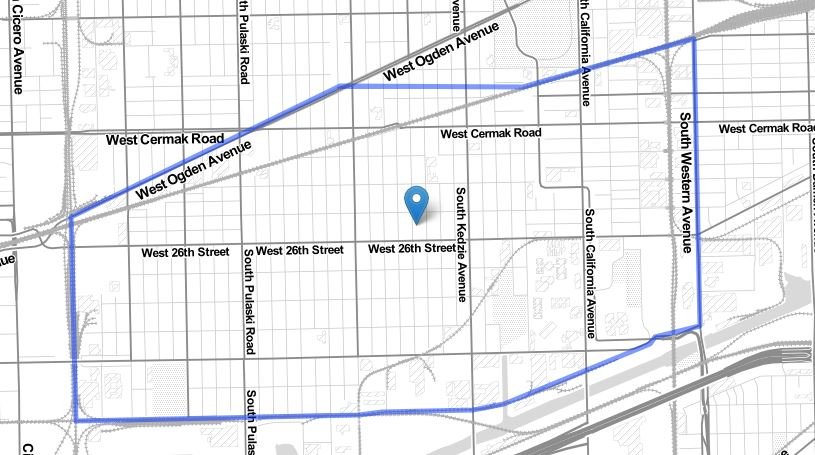

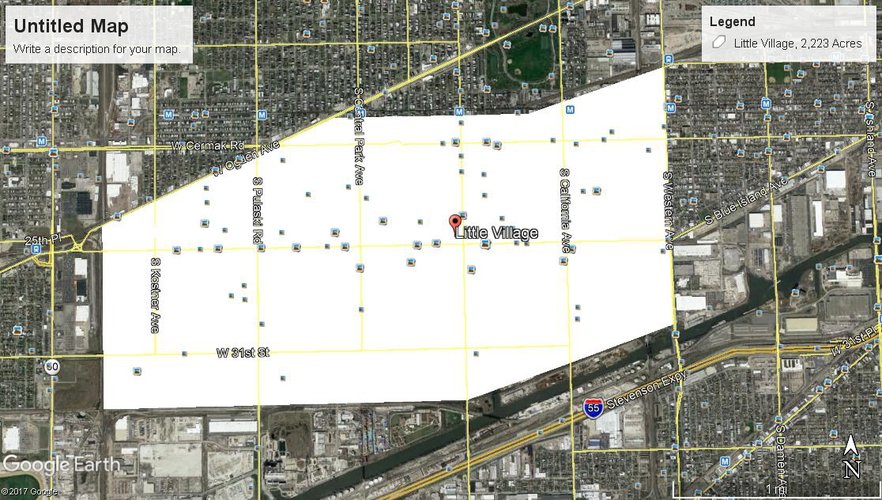

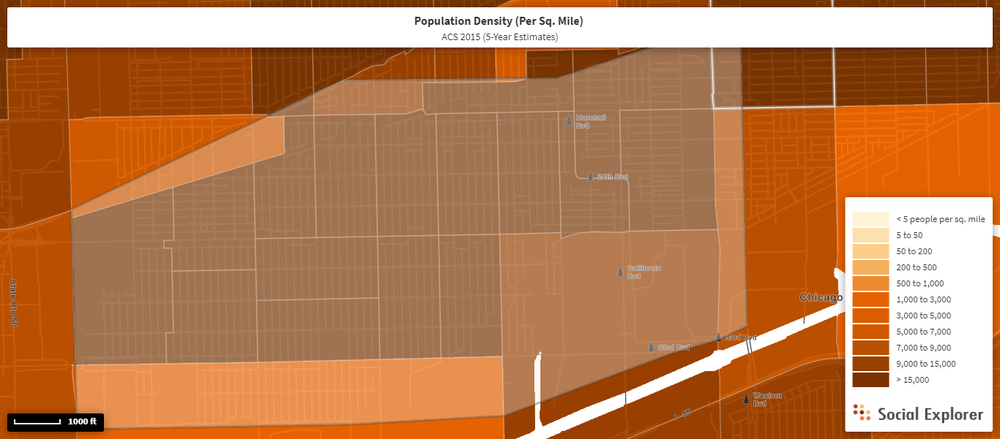

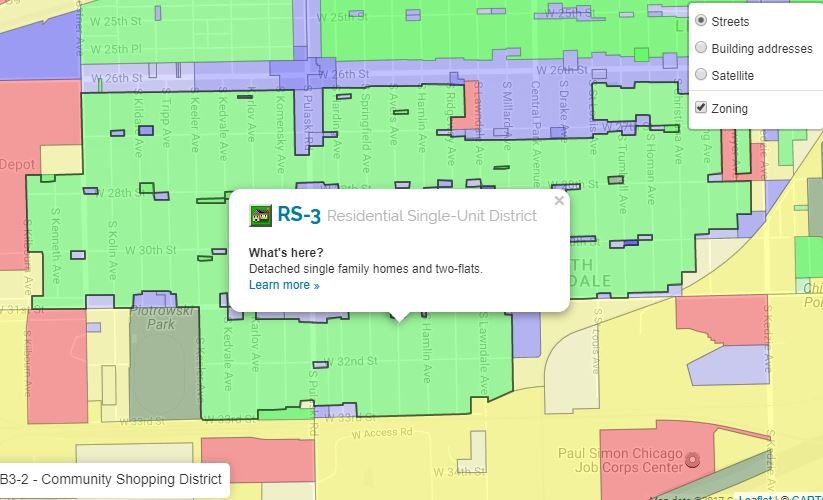

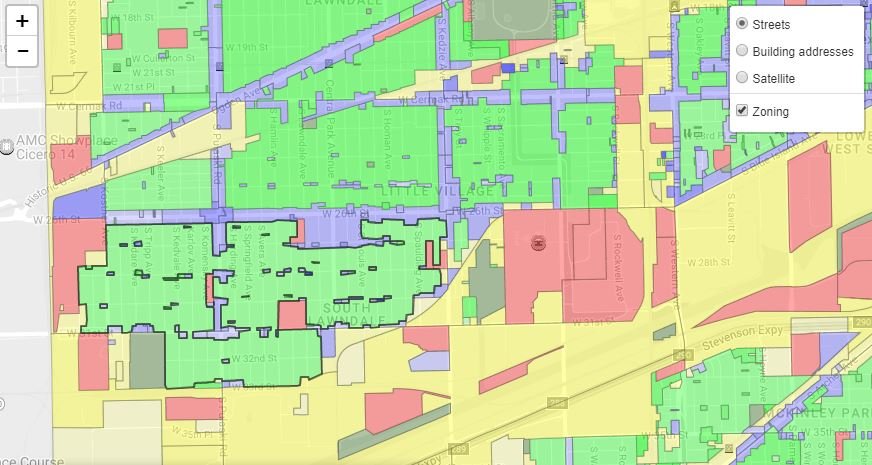

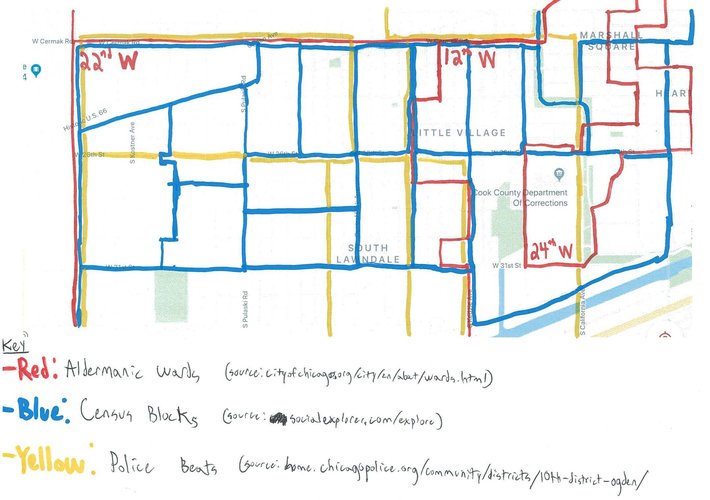

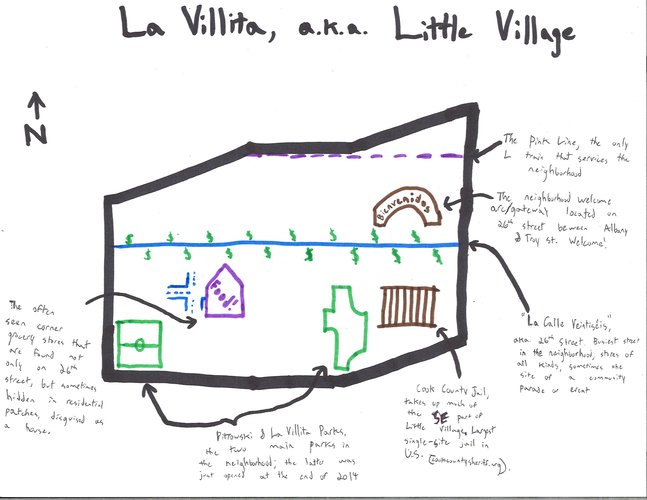

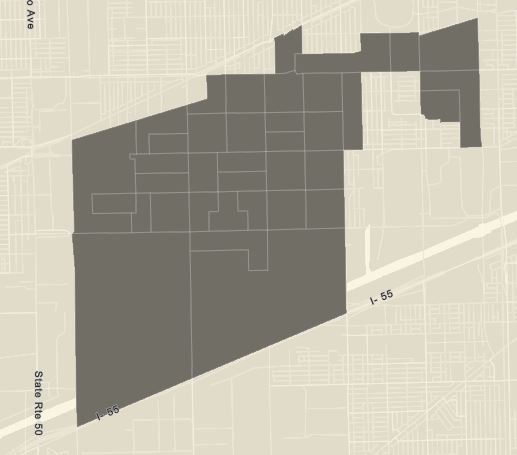

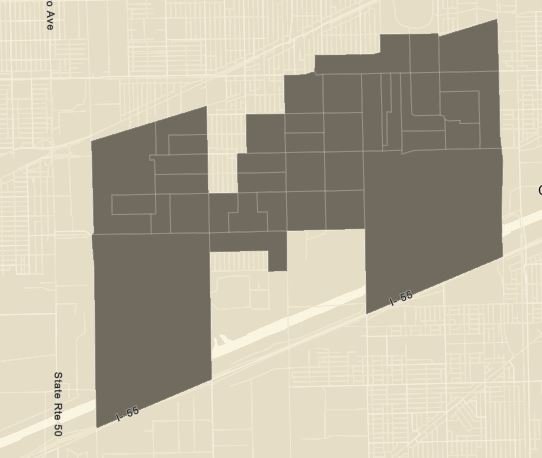

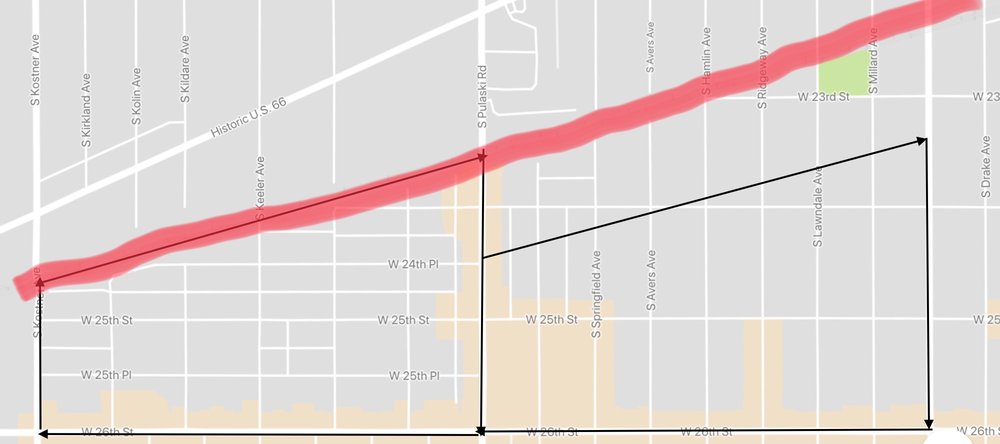

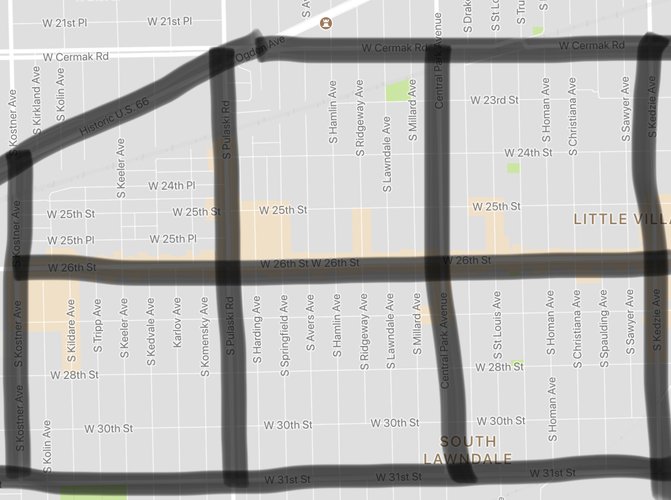

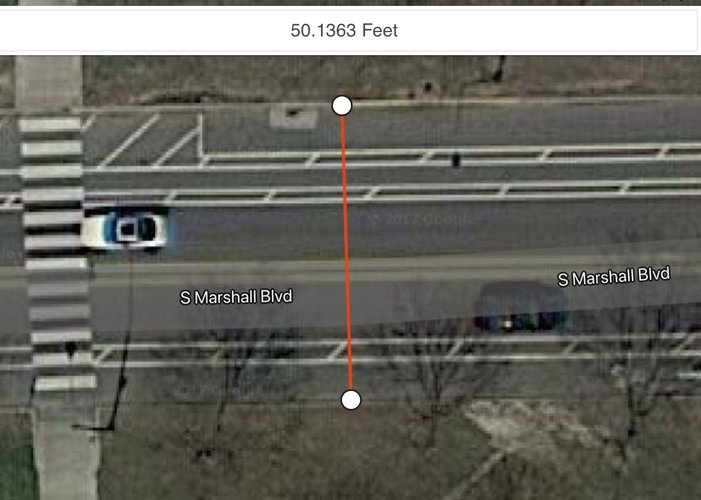

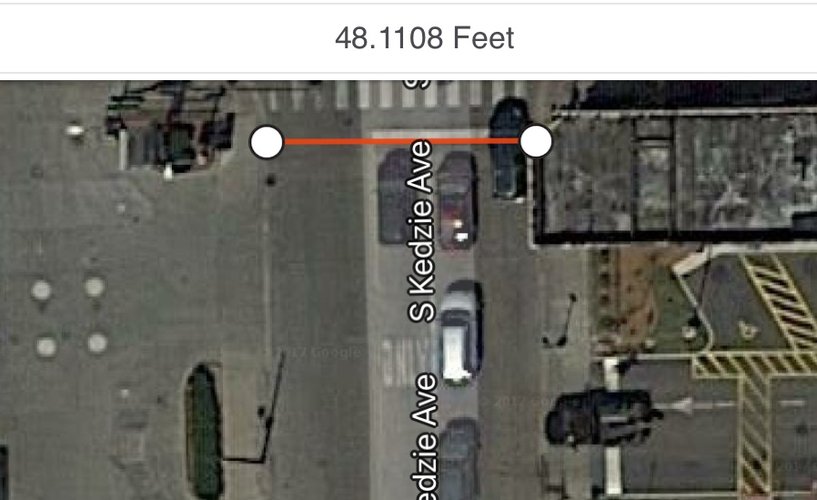

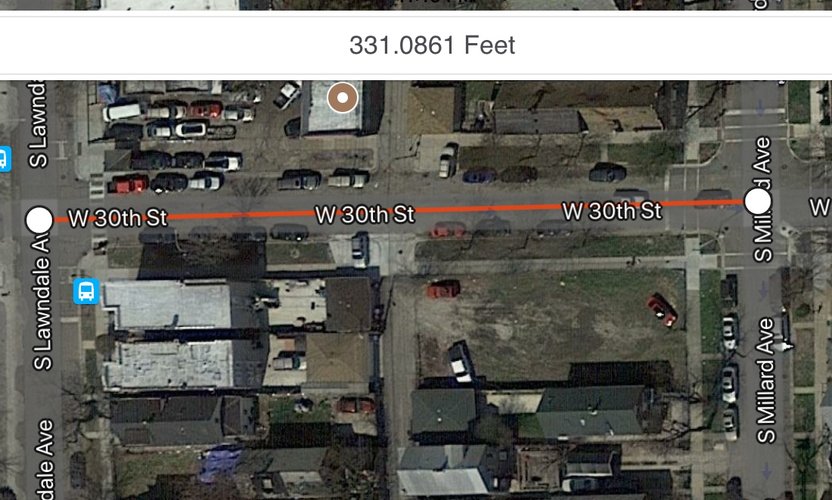

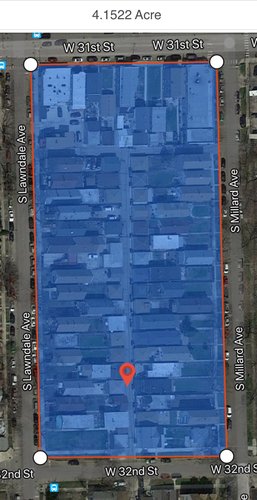

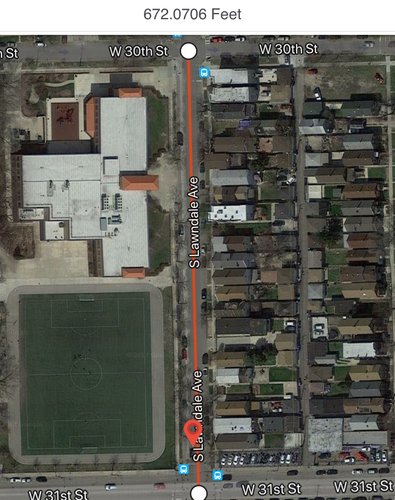

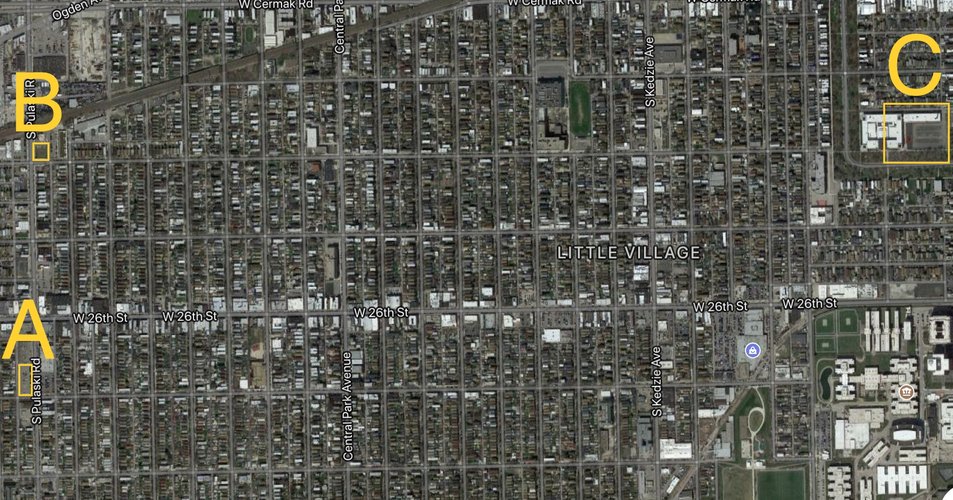

Little Village, also known as La Villita or South Lawndale, has ample coherence; it’s made abundantly clear by the “Bienvenidos a La Villita” (“Welcome to Little Village”) gateway that resides on the east side of the neighborhood in between Troy and Albany ave leading westward onto 26th street. Little Village has a distinct identity throughout the entirety of its boundaries, made possible in part by its large presence of Mexican and Mexican-American residents who give the neighborhood its Mexican character. However, there are some areas of the neighborhood that seem to be divided in such a way that doesn’t necessarily disrupt Little Village’s collective identity, but does differentiate some parts of the neighborhood from others. For instance, the neighborhood is thought to have a distinctive residential area along its southern border, with the residential area between 3100 and 3300 S blocks being mentioned in some literature as “the burbs” (Vargas 2016, 66, 69). This area is characterized by its lower density; upon survey of the neighborhood, this seemed to be because this area had higher abundances of low-density, single family homes (see images 1 and 2). This is confirmed by a zoning map of Chicago that shows this area to be zoned for single family homes (see image 3). Additionally, the neighborhood is thought to have both a west side and an east side, with the east side of the neighborhood being east of Marshall Blvd (more or less east Kedzie) and continuing east until Western Avenue. Interestingly, there has been a recent push by some of the local community organizations on the east side of the neighborhood to refer to that part as “Marshall Square” (Vargas 2016, 181), but this change seems to still be in development and appears to be the result of larger sociopolitical issues. Still, the east side of the neighborhood is delineated by the large, commercial avenues to its eastern and western boundaries (Kedzie and Western Avenues) and roughly Cermak Avenue to the north and the Cook County Department of Corrections and a nursing home to the south.

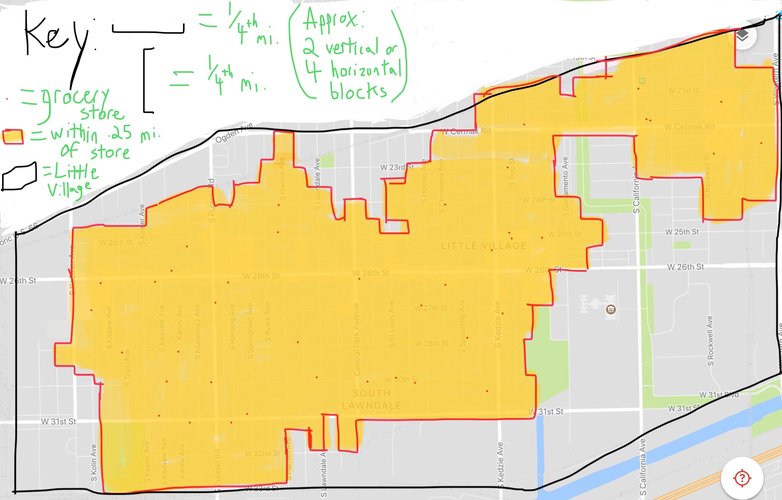

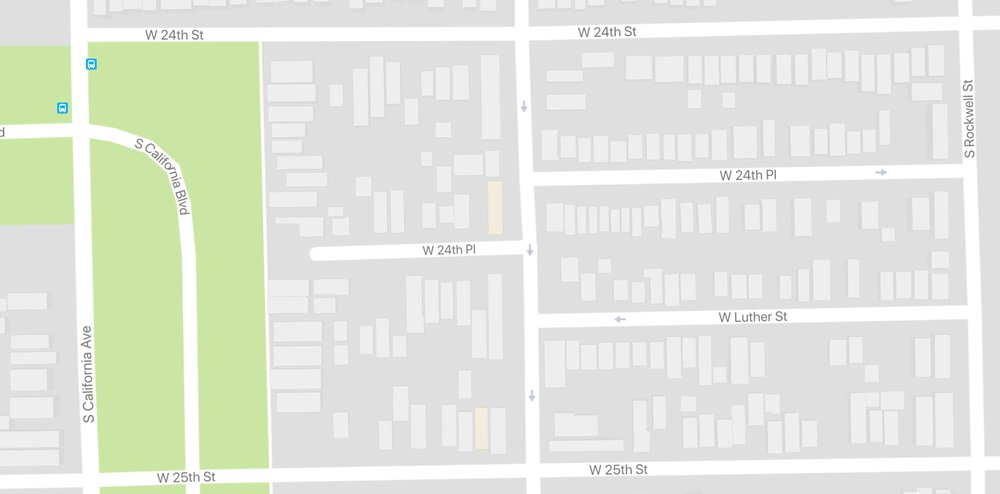

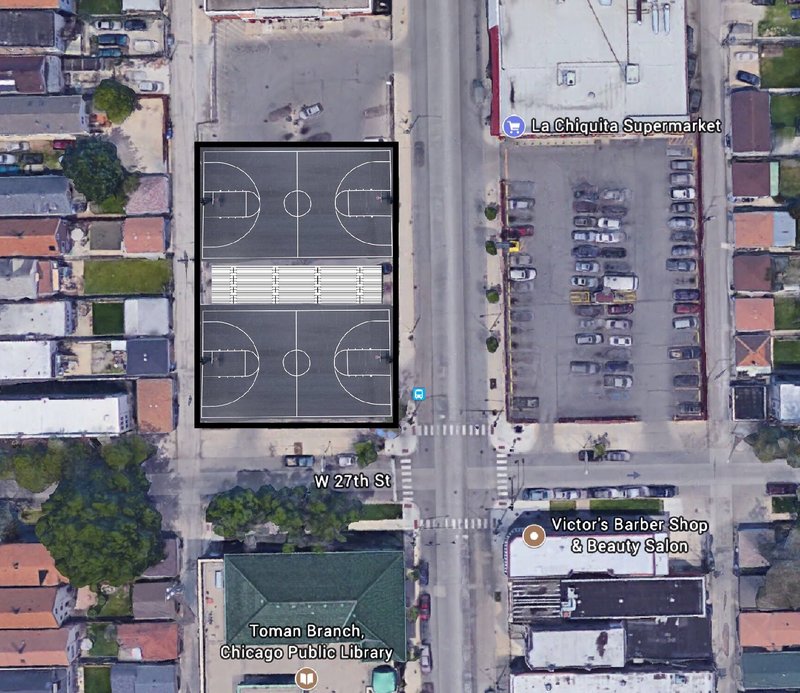

These areas, though distinctive, all still refer to themselves as Little Village, as many of the retail stores or restaurants will put Little Village or La Villita in their name. What also makes this neighborhood distinctive throughout the neighborhood is its predominantly Mexican population that is like such throughout the neighborhood, not just in particular parts; many of the stores in the neighborhood are named in Spanish, advertise in Spanish, or provide both English and Spanish signage and advertising. An easy sign of this is the neighborhood’s 26th street commercial area (also known as La Calle Veintiseis [26] or simply “La Veintiseis” in Spanish). The street stretches right through the middle of the neighborhood, serving the populations to the north and south of the street, and is lauded as the second biggest source of tax revenue for the city of Chicago, second only to Michigan Avenue according the Chicago Reader. The streets have everything one can think of or need, including laundromats, restaurants, clothing stores, grocery stores, convenience stores, music shops, retail stores, banks, flower stores, liquor stores, and many other stores along with street vendors. I say this not to provide mere description of the neighborhood, but rather to argue that this helps to centralize and characterize the neighborhood. It makes perfect sense that 26th street is not the northern or southern border of the neighborhood because both residential areas to the north and south of the street frequently use this street for daily needs. In addition, the street is also used by neighborhood organizations for events like 5k running events or the annual Mexican Independence Day Parade, providing the area a communal identity. The neighborhood’s borders also make complete sense and provide the area with a distinct identity if one simply looks at the neighborhood through the eyes of its zoning codes (see Image 4). The neighborhood is bordered to the west by Cicero and to the east by manufacturing districts, railroads, and the Cook County Department of Corrections. It’s bordered to the north by Ogden Ave and Douglas Park, and to the south by manufacturing districts that lie a block or two away from the Chicago River and Stevensen Expressway. Hence, the neighborhood’s borders are either manufacturing, non-residential districts, city limits, parks, railroads, or main streets. Overall, the neighborhood’s shape and boundaries make sense, and the neighborhood seems to have a collective sense of identity.

See more images of places throughout Little Village below.

Sources: Vargas, Robert. Wounded City: Violent Turf Wars in a Chicago Barrio. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Zoning Map found at: www.secondcityzoning.org/

The History of Little Village

After the annexation of the Lawndale area in 1869 and after the Great Fire of 1871, there were two wealthy businessmen, Alden Millard and Edwin Decker, who decided to invest in and build an affluent Anglo-Saxon neighborhood in what now would be considered Little Village. The location was ideal for its fair price and the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy railroad which ran through the area. It the beginning of the 20th century, the neighborhood began developing a sizable Polish population, which sought to rename the neighborhood Pulaski from its original name, Crawford. The neighborhood began to grow in the first thirty years of the century as factories and rail yards were built along the neighborhood’s perimeter. As Czechoslovakian and Eastern European immigrant groups began to accumulate wealth, they moved away from the crowded Near West Side and pushed out the wealthier Anglo-Saxon residents who were residing in the neighborhood, replacing sizable brick buildings with bungalows and two-flats. The Czech population there flourished by WWII with the advent of industrial jobs moving into the neighborhood, and 26th street became known as “Czech California.” As African-Americans moved into North Lawndale in the 1950s and 60s, the neighborhood tried to distance itself from the growing Black populations and the socioeconomic disadvantages that came with being a Black neighborhood in this time period; it was rebranded as “Little Village” after the neighborhood’s significant Eastern European population. As UIC began to be built in the Near West Side, many Mexicans in the neighboring Pilsen area were pushed into Little Village while whites and white immigrants fled the neighborhood to the more prosperous suburbs either because of the changing neighborhood demographics, better quality of life, or better economic opportunities. The neighborhood quickly became predominantly Latino over the next twenty or thirty years, and by 1991 the neighborhood was gifted its famous “Bienvenidos a Little Village” arch by the Mexican government.

The neighborhood seems far from poorly or mistakenly planned, but rather it seems it has a clear history of why the neighborhood is the way it is today. 26th street from the very beginning of the 20th century emerged as a commercial hub—just not with predominantly Mexican family working the stores at the time. What was crucial to the early development of Little Village was clearly its manufacturing and industrial sectors and the presence of rail lines and rail yards. For instance, Binford notes that post-Great-Fire, “the most powerful actors in this new gridded landscape…were those who had the means to deal in property” (Binford 2008, 44). This was exactly true of Peter Crawford, who gave some of his land in the area to Chicago, Burlington, and Quincy railroad so that there would be a railroad stop in the area. As a canal was built to the south of the neighborhood and a factory to the west in the early 20th century, it’s clear that Little Village began as one of the many manufacturing communities that blossomed after the Great Fire of 1871.

Sources: Binford, Henry. 2008. "Multicentered Chicago" In Keating, Ann Durkin, ed. Chicago Neighborhoods and Suburbs. Pp. 41-54.

All other information gathered from two articles:

https://www.wbez.org/shows/wbez-blogs/south-lawndale-aka-little-village/08cd0f0a-248a-464d-84ec-75995bc6bec4

http://www.enlacechicago.org/littlevillagehistory

Social Mix

On Little Village's Diversity

According to the indices used in the image below, Little Village is not a diverse racial neighborhood. As seen in census statistics, the neighborhood is predominantly Hispanic with relatively few other ethnic minorities and whites. Compared to Chicago and the West Region, Little Village isn't even close to having a diverse racial neighborhood. However, the neighborhood is diverse in regards to age (with the categories being 25-34, 35-44, 45-54, 55-64) and levels of education (with the categories being less than high school, high school diploma, some college, and bachelor's degree and above). It's age diversity is high and matches up competitively with the West Region and Chicago, though Chicago is a bit more diverse in education levels than is Little Village. In addition, though not in the tables, it is clear that Little Village has little income diversity as well. Many of the residents are far below the median income in the city as a whole, and the neighborhood has a significant level of poor residents compared to the West Region and Chicago.