Overview

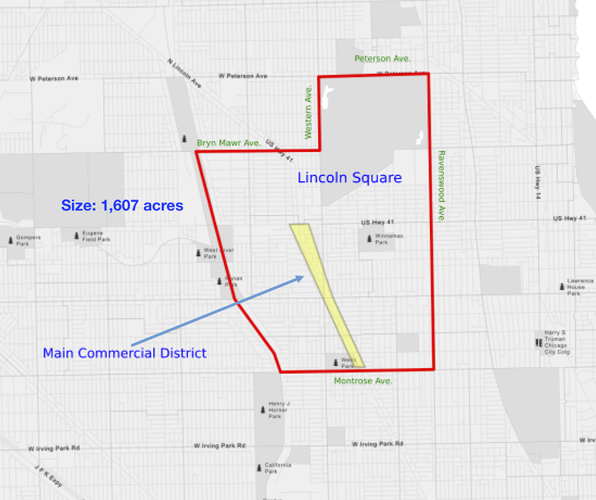

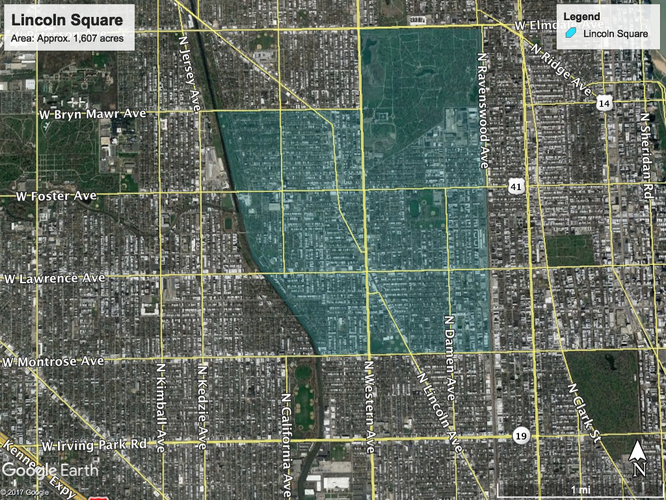

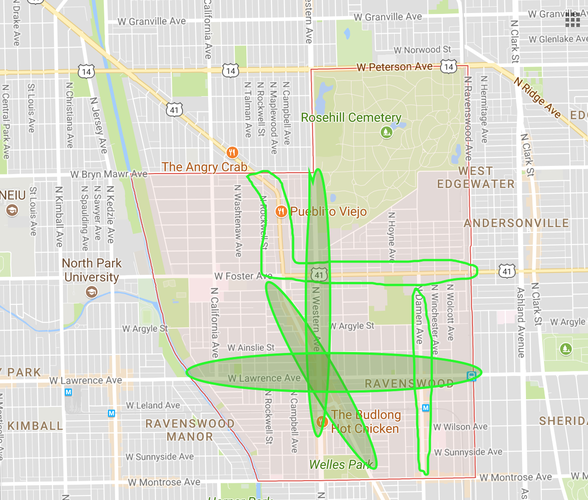

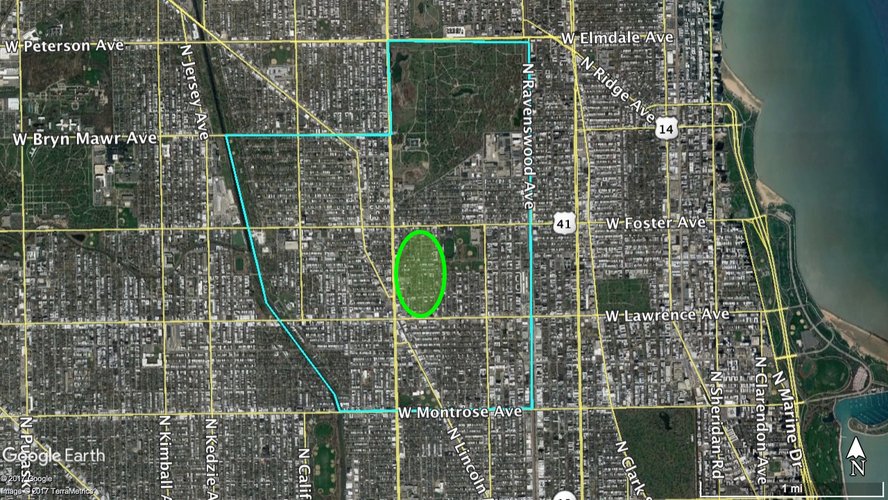

Size

Identity

Chicago’s Lincoln Square neighborhood currently lacks the sense of neighborhood identity which it once might have had. Walking around the main commercial area, on N. Lincoln Ave, there are clear allusions to the area’s German and eastern European past: there is a specialty foods market with German cuisine, a traditional sausage eatery, and a bar whose façade is covered in German flags. That is essentially all there is with regard to a cohesive territorial heritage. The majority of stores in Lincoln Square are the type one would expect to see in a neighborhood in the last stages of gentrification; there’s an independent bookstore which doubles as a beer and wine bar; a bourgeois kitchenware store; an overpriced, locally-produced clothing store; and a “general store” selling expensive candles, Chicago-branded wine glasses, and other knickknacks. That is to say, the commercial district of Lincoln Square is incredibly white, but upper-middle-class, liberal, American type of white. Most of the eateries on the main drag reflect this. The only ‘diverse’ cuisines represented are Greek and Mexican, and there are, effectively, one of each. But there are plenty of cafés which specialize in fair-trade, organic brews (my iced Americano only cost $4)!

The makeup of Lincoln Square’s commercial district betrays its current demography. The neighborhood is roughly 64% white, with the majority of the other population being Hispanic, black, and Asian.[i] The looks and makeup of the neighborhood whitewash its population. Despite the undeniable diversity of pedestrians, the institutional aspect of the neighborhood ignores this and gives the impression that it is, essentially, a whites-only community. This speaks to the disconnect between what a theoretical neighborhood is and the inherent diversity of city populations.

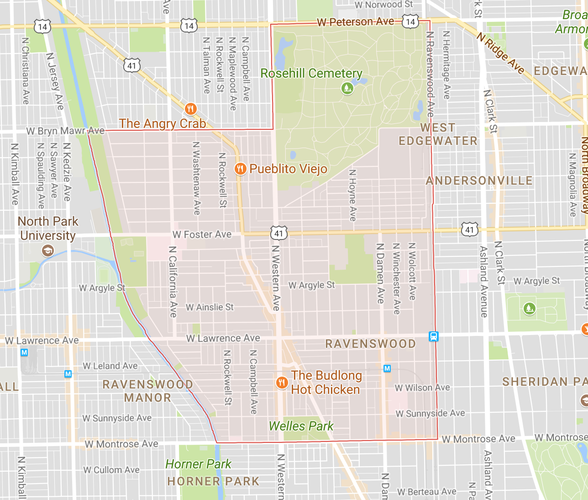

Despite this neighborhood-like homogeneity, Lincoln Square still does not feel like a neighborhood. Rather, it feels like its own micro-city within the boundaries of Chicago. Lincoln Square, in partnership with the adjacent Ravenswood neighborhood, even has its own chamber of commerce. It seems like Lincoln Square has its own sub-neighborhoods, such as the main commercial area, and the stretch of N. Lincoln Ave just north of it where there are less boutique-y, big box stores. This is to say that no, downtown Lincoln Square does not have a cohesive sense of neighborhood identity. (The other commercial areas are more different.)

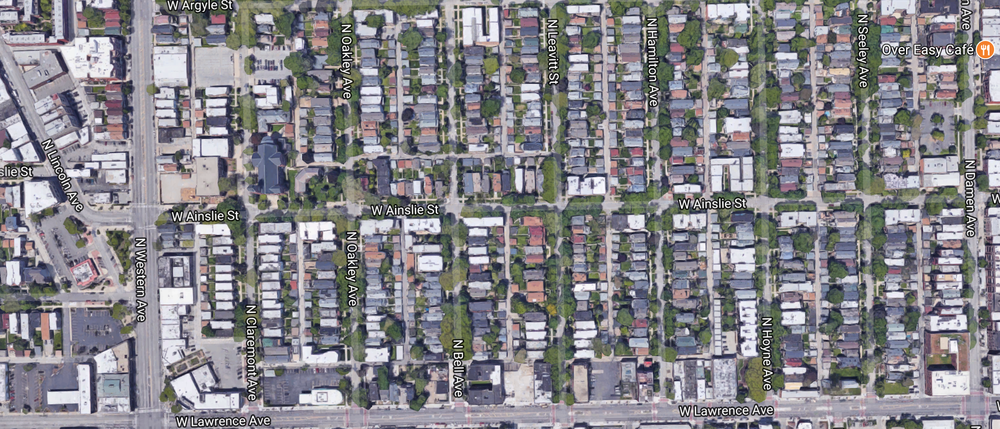

The residential area of Lincoln Square furthers this point. The only architectural cohesion is that many of the single-family homes are done in the classic Chicago Bungalow style. Yet even the bungalows can look radically different, save for their basic shape and features. While this does identify Lincoln Square as being one of the more historic neighborhoods, it does not mark it as being one specific neighborhood. Chicago Bungalows are present in many different parts of the city, and their being in Lincoln Square does not afford it a sense of neighborhood identity.

No parts of Lincoln Square presented a sense of a cohesive neighborhood identity. This begs the question, though, of whether a truly diverse neighborhood can still be aesthetically, commercially homogenous.

[i] https://statisticalatlas.com/neighborhood/Illinois/Chicago/Lincoln-Square/Race-and-Ethnicity

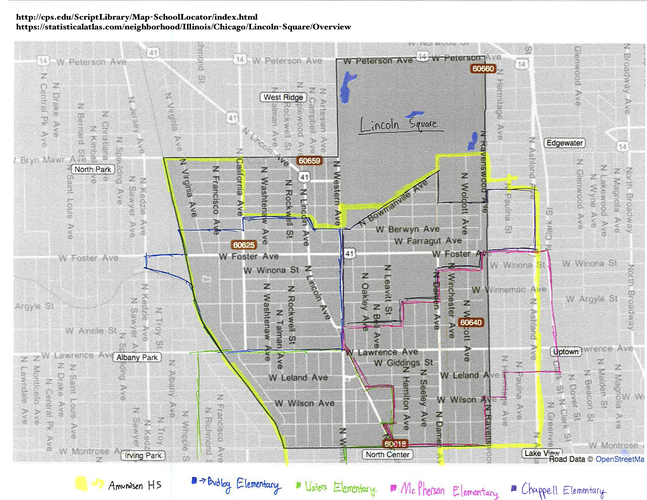

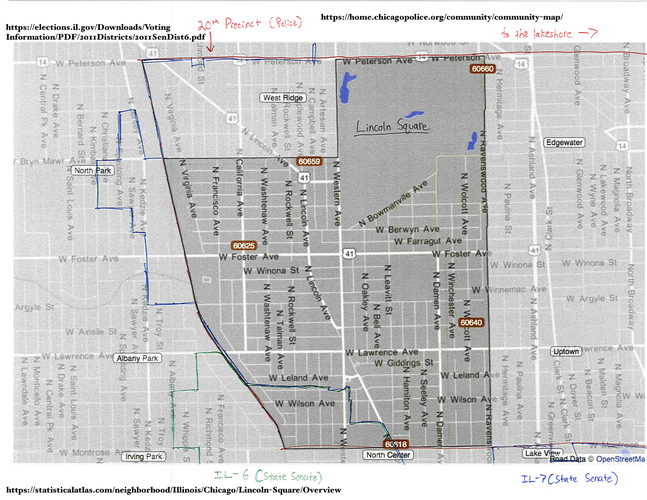

Layers

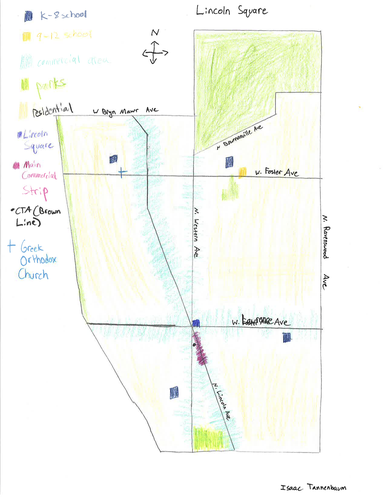

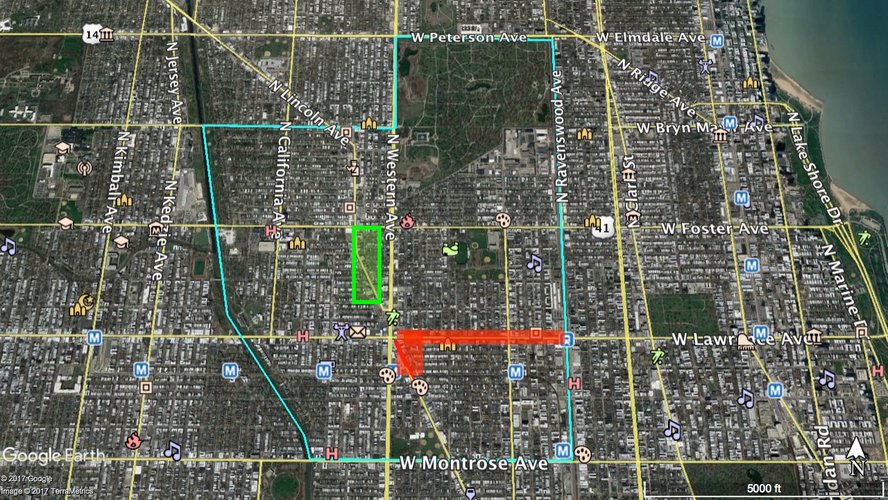

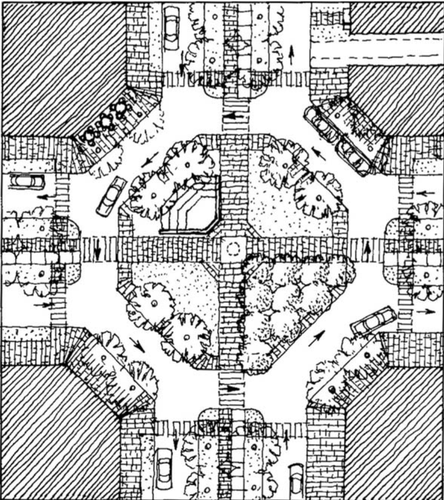

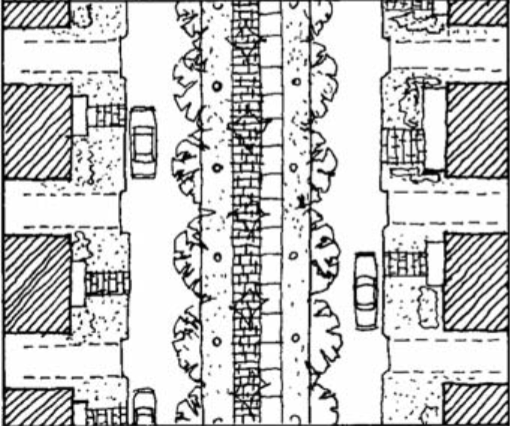

Diagram

History

Chicago, 1836: Swiss-born farmer Conrad Sulzer buys a plot of land to the northwest of downtown. Other agrarians quickly followed suit, especially those of German and English heritage. These farmers dealt mainly with celery, giving name to the area’s reputation as being the celery capital of the world. In addition to the green vegetable, the men would cultivate flowers and jar pickles; they would then make the trek to downtown Chicago to market and offload their goods. These farms and crop factories employed hundreds of Polish workers from around the city, whose seasonal migration to the area prompted the opening of handfuls of Eastern European pubs and bars around the main intersections. This neighborhood of Chicago is today known as Lincoln Square.

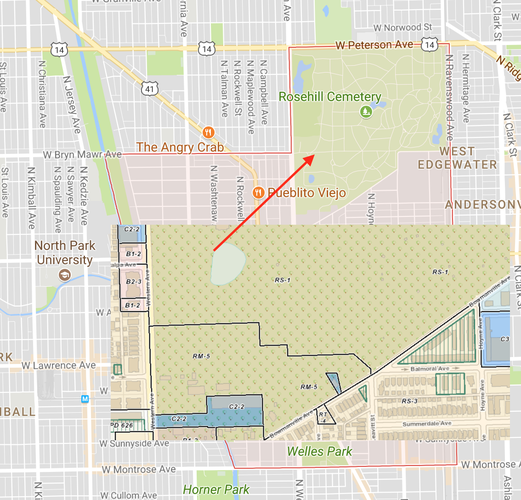

The neighborhood’s first residential subdivision, known as Bowmanville, was established around the 1850s, shortly followed by the demarcation of the Rosehill Cemetery in ’59. When the Ravensville Elevated train line opened in the early 1900s, new residents flocked to the city. The neighborhood’s farmland began to be filled with the famous Chicago bungalows––though many residents were white, new demographic groups began to pop up. This included many Greek Chicagoans immediately following the construction of the east-west artery that is the Eisenhower Expressway. Its development required the razing of what was then Greektown and prompted the large-scale migration of Greek immigrants to the Lincoln Square area. In fact, so many Greeks moved to the neighborhood that it became known as the New Greektown. Though their presence has since become significantly less noticeable, their mark on the neighborhood’s history is certainly undeniable. Remnants of this past are noticeable today in the handful of Greek eateries along the main commercial drag.

Despite its continued reputation as being a neighborhood of Germans and Eastern Europeans, the past few decades have seen an increased diversification of the Lincoln Square. The 2000 census notes that roughly 25% of Lincoln Square residents are Hispanic, and 13% are of Asian descent. This much is clear from visiting the neighborhood. In the fashion typical of modern cities, restaurants catering to natives of their respective cuisines dot the streets surrounding the main shopping boulevard. Unsurprisingly and unfortunately, though, this diverse heritage is mainly ignored on the main drag save for one Greek restaurant and an Americanized, Mexican, fast-casual eatery.

Lastly, the history of ‘Lincoln Square’ as the neighborhood’s name must be addressed. The area had commonly been referred to as “Ravenswood”, an allusion to the prominence of residential areas within its boundaries. In 1925, however, the Chicago City Council declared it to be called Lincoln Square, and roughly one score and ten years later, a statue of its namesake was erected at the entrance to the main commercial strip (which also happens to be on N. Lincoln Ave).

Source:

“Lincoln Square.” The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago: Chicago Historical Society, n.d. Web. 9 October 2017.

Social Mix

The following tables contain demographic information for the Lincoln Square community area of Chicago. The latter 4 tables employ the Simpson Diversity Index in order to quantify how diverse the neighborhoods actually are.

Based on the variables explored, it is fair to conclude that the Lincoln Square neighborhood of Chicago is somewhat homogenous, especially in comparison to the city’s demography. This is most apparent in the variable of race. The Simpson Diversity Index calculated the neighborhood as scoring a 2.2 out of a possible 6 with regard to its racial diversity. That is to say, the vast majority of residents fell into one or two categories: white and Hispanic. This is significantly lower than Chicago’s SDI for race of 3.5, though this does not mean that Chicago is diverse as a city, either. Lincoln Square was more diverse when it came to household types, having scored a 3.4 out of a possible 5. It was interesting to see that there were roughly equal numbers of male and female homeowners who did not have a family. This points to Lincoln Square being a neighborhood with both families and childless-individuals. The fact that there are very few single-parent homes explains why the SDI is not a perfectly diverse 5, as these were two more categories into which the population was divided. Lastly, Lincoln Square is very diverse with respect to the education levels of its residents, with the Simpson Diversity Index being a 4.2 out of a possible 5. It trails Chicago closely, with the city scoring 4.8.

Despite strong diversity regarding education, the most salient feature of Lincoln Square’s demography is its racial homogeneity. A whopping 64.5% of its population is white, which is over twice the relative percentage for Chicago as a whole. The experience of walking through Lincoln Square––arguably how one encounters its qualitative demography––conveys the same message as this quantitative analysis. The neighborhood is very white, and the stores in the main commercial area seem to cater to younger families, as well as relatively young urban professionals.