Overview

Size

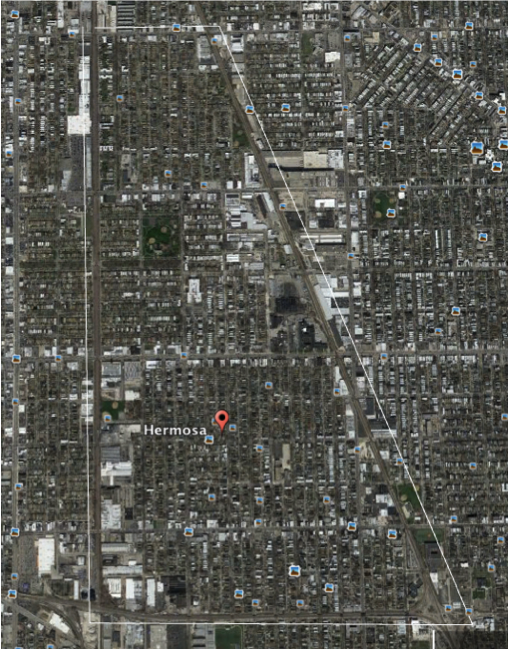

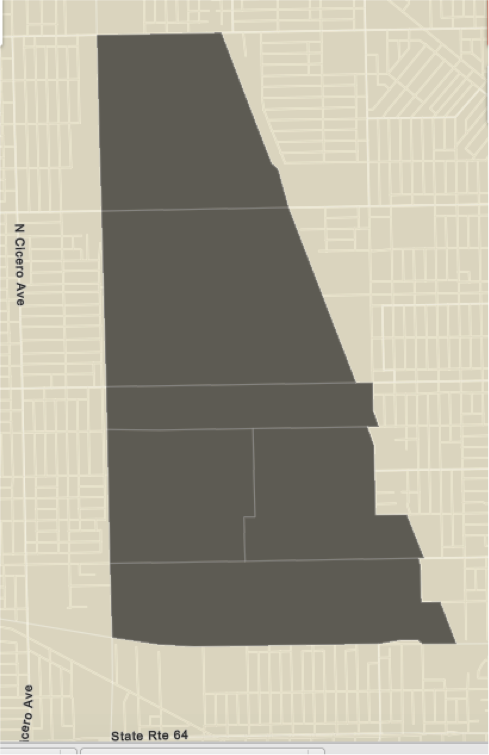

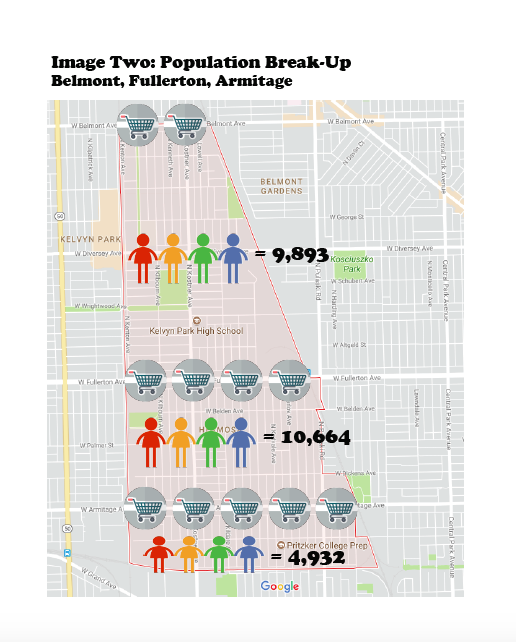

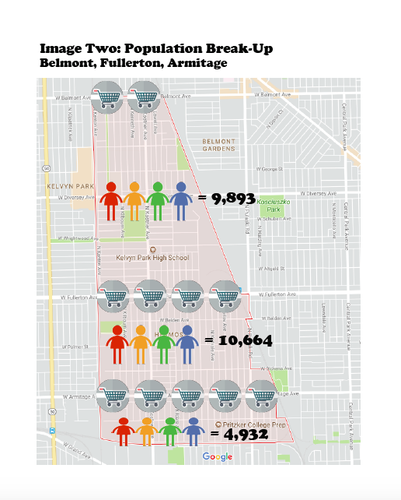

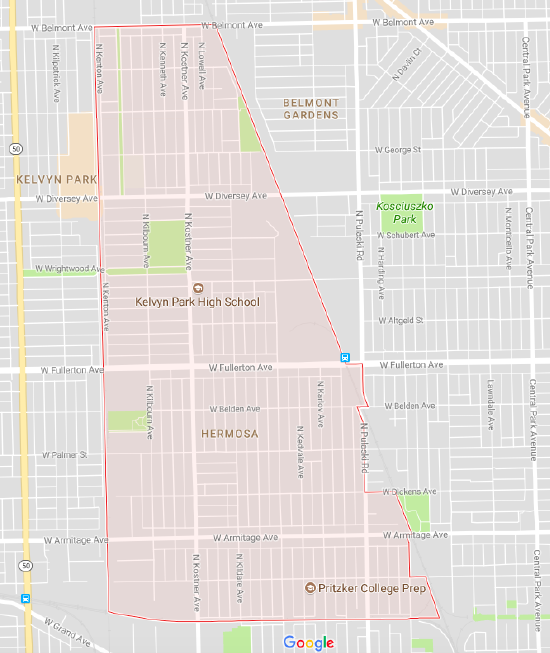

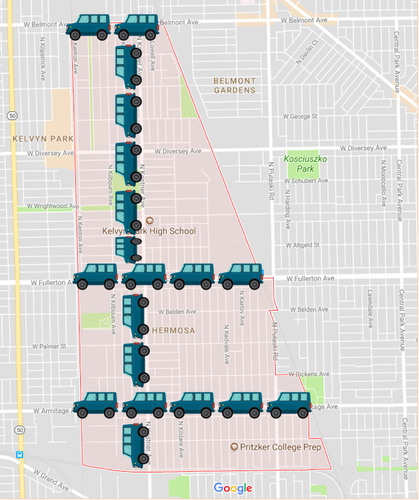

According to Social Explorer, Hermosa hosts about 25,489 people. To calculate Hermosa’s population, I combined the populations of census tracts 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004.01, 2004.02 and 8312, since they almost perfectly align with Hermosa’s perimeter (as defined by the Chicago Encyclopedia).

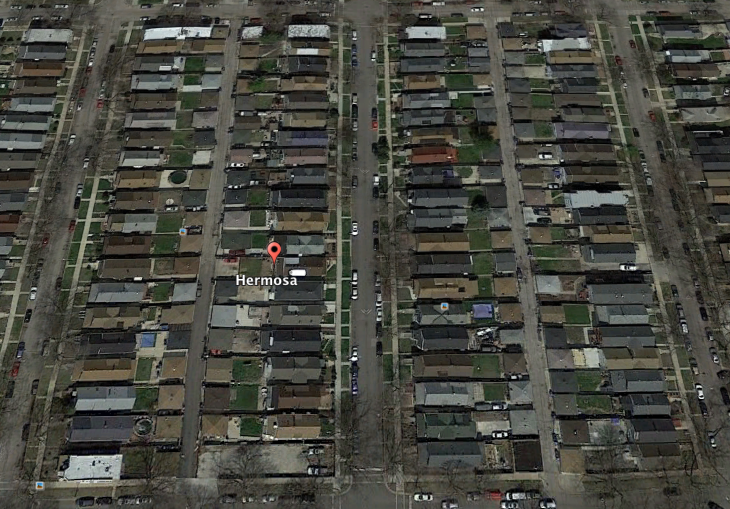

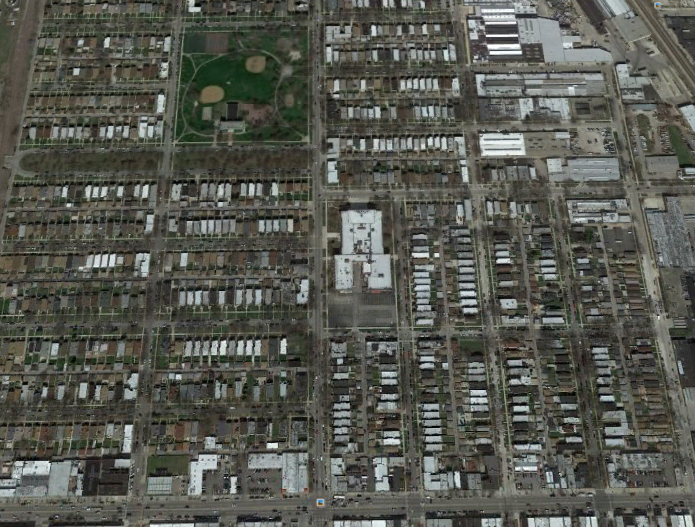

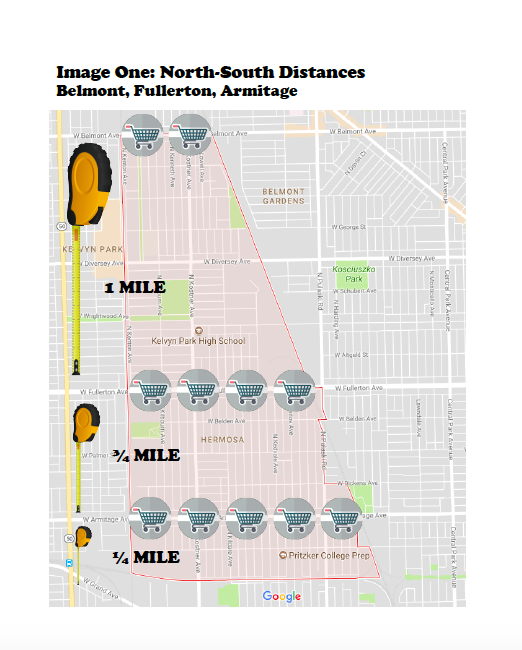

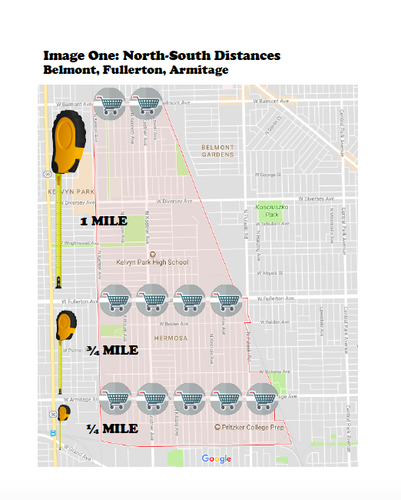

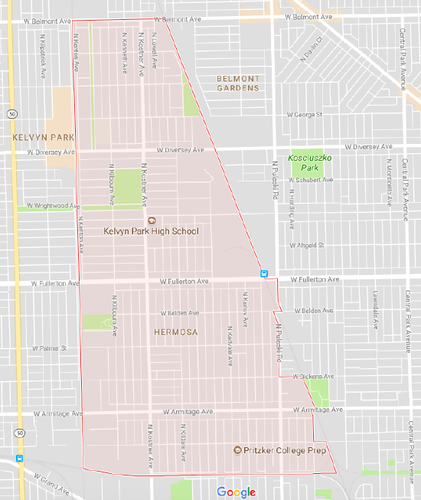

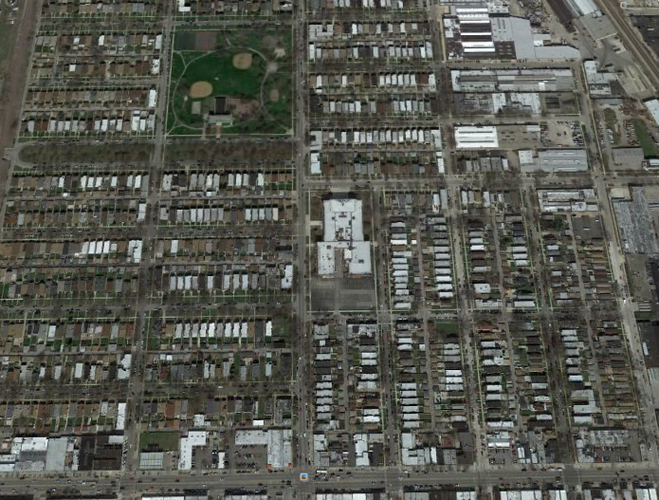

Stretching about 1.17 square miles, Hermosa is one of Chicago’s smallest and most densely populated Community Areas (Google Earth). Geographically, Hermosa exceeds Perry’s ideal neighborhood unit size (1 square mile) only slightly (Perry). Hermosa's population, however, qualifies more as a 'sub-district than a neighborhood unit: bigger than a street neighborhood but smaller than a city (Jacob). With over 25,000 people, Hermosa can both self-govern on local issues and also receive City services.

Layers

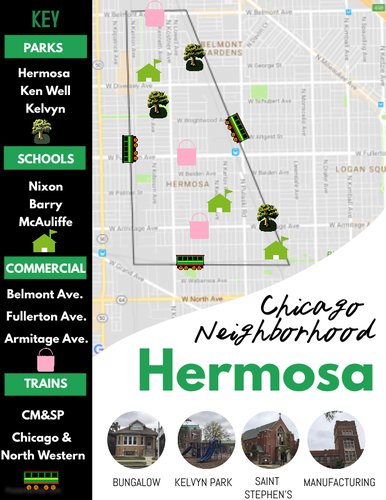

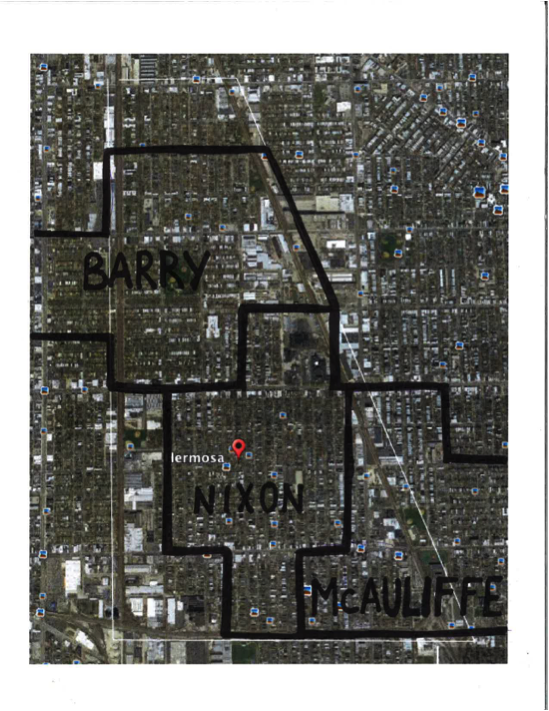

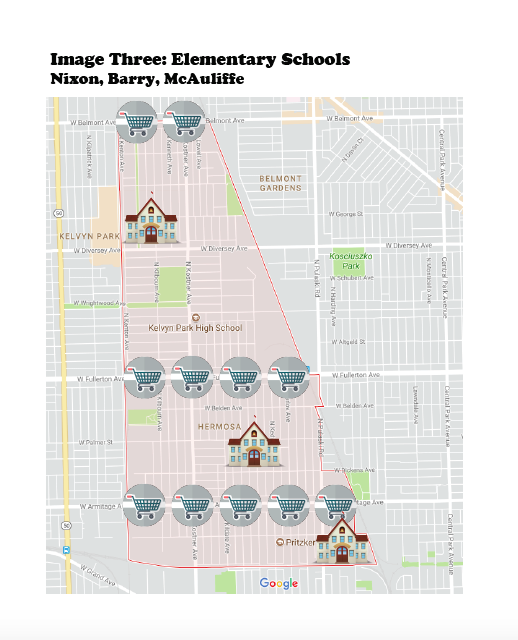

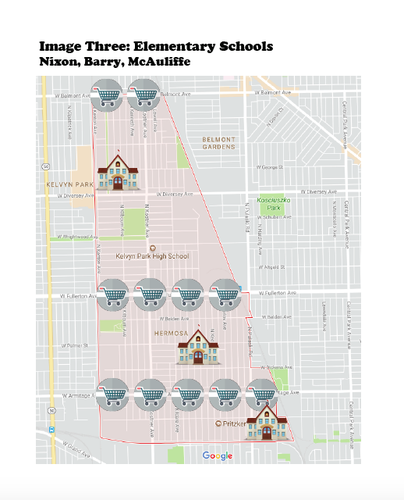

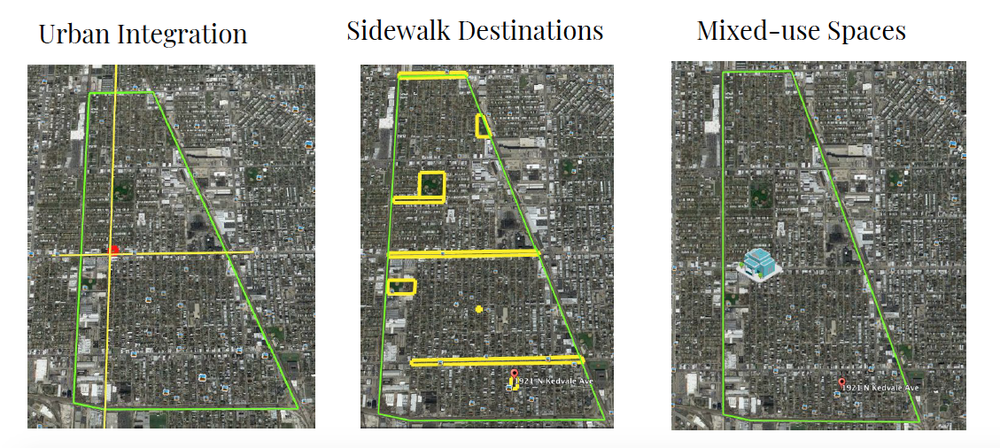

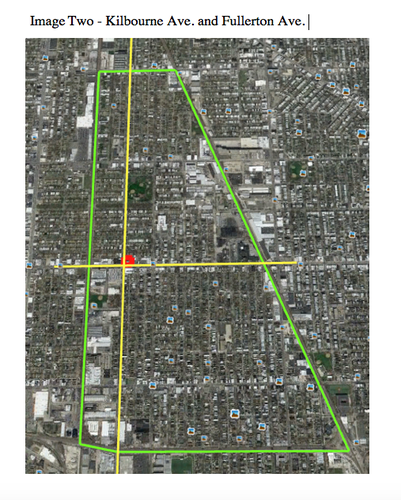

To understand Hermosa spatially, we can study the other types of districts surrounding and encompassing Hermosa's borders. Below, I have broken Hermosa into census tracts and elementary school districts.

Census Tracts: Hermosa follows 2014 census tracts rather closely. Census tracts 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004.01, 2004.02 and 8312 all fall within Hermosa’s boundaries.

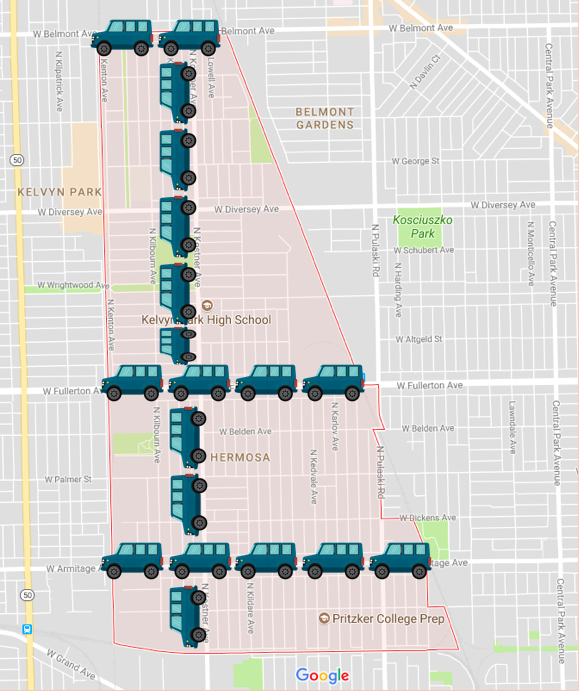

Elementary School Districts: three public elementary schools serve the Hermosa Community: William Penn Nixon, Barry, and McAuliffe (Schools in Hermosa). Below, I have drawn the district lines. In Perry’s neighborhood unit, he suggests that each neighborhood have one elementary school. Hermosa has three, however they each serve 600-1000 students, as Perry suggested.

Identity

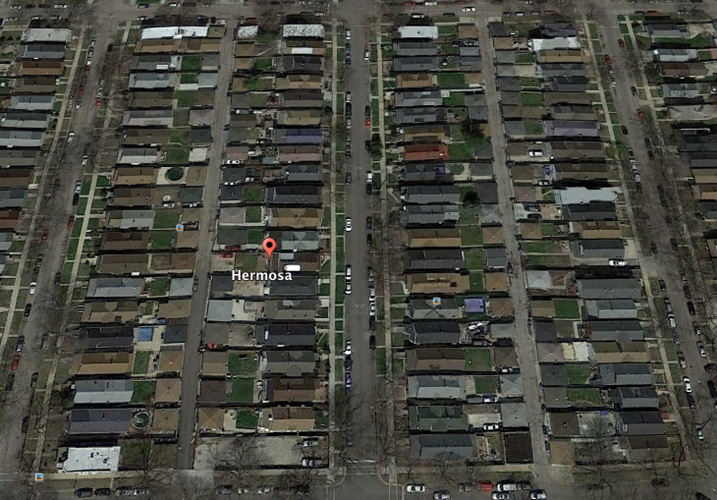

Bordered by three railroad tracks and a busy commercial street, Hermosa has clear and distinct boundaries. Within Hermosa’s boundaries, there are three parks, three elementary schools, and three commercial streets, all equitably spaced, giving the neighborhood a pattern and sense of uniformity. Between the schools and commercial areas, small brick bungalows and colorful two-story flats form a tight grid. While the bungalows vary in color, their shape, style and green spaces are almost identical. Even the schools and apartment complexes mirror the homes' architecture: brick, simply shaped, and low to the ground.

Due to Hermosa’s spatial and stylistic repetition, I, as an outsider, do not notice any sub-groups or neighborhoods. If anything, I notice a slight wealth and ethnic gradient running north to south. In the southern third of Hermosa, especially along Armitage Ave., every store operated in Spanish. The houses in this area were loved, but often warn down. As I walked north, stores and signs were in both English and Spanish. Homes were slightly more up-kept, hinting at an increase in wealth. Walking north still, the houses grew. Parked cars seemed newer and in better condition, and the social demographic shifted from almost completely Hispanic to a well-mixed group of Hispanic, black, and white residents.

Despite this slight gradient, Hermosa’s repetition of services, signage, street pattern and architecture gives the neighborhood coherence and charm. Every commercial street has an enormous selection of services—medical clinics, laundromats, beauty salons, childcare centers, grocery stores, restaurants, hobby shops, community centers, clothing stores, and churches—all catered to the community’s needs. Since residents are never more than a five-minute walk from these services, I anticipate strong ‘weak’ ties.

In addition, the Hermosa community seems to adhere naturally to its borders. The neighborhoods to the west and east of Hermosa have similar commercial areas, however there is a visible racial divide between Hermosa and Kelyvn Park (its western neighbor). North of Belmont, the houses quickly grow in size and variety, and the demographic shifts from majority Hispanic to majority white. Additionally, a new and towering apartment complex lines Belmont, loudly announcing Hermosa’s north-most boundary.

Lastly, several community improvement organizations

unite and decorate Hermosa’s public spaces. Throughout the neighborhood, the

Hermosa Neighborhood Association has posted signs encouraging residents to

maintain the parks and care for their neighbors. Other organizations planted

small green spaces in-between busy streets. In all, these community efforts, as

well as the unified architecture and strict borders, give Hermosa a noticeable

but modest sense of identify.

History of Hermosa

Hermosa: beauty in Spanish, home in Chicago. Resting about six miles northwest of the Loop, Hermosa hosts one of Chicago’s oldest and most historically rich residential communities.

Settlement in Hermosa began around 1855 when the Chicago Milwaukee and St. Paul (CM&SP) Railroad built stop in the area (Perry, Marilyn). In the following decades, Hermosa’s sweeping flat lands and proximity to downtown attracted factory owners and manufacturers. Seeking employment, Scottish immigrants soon followed. By the end of the 19th century, several factories operated in Hermosa, including the Expanded Metal Company and Eclipse Furnace (Hermosa).

Of all the industries that fled into Hermosa, the Schwinn Company may be the most famous. Schwinn, the country’s leading bike manufacturer until the 1980s, attracted thousands of factory workers, all of which needed homes (Tour). These workers built small bungalows near the CM&SP tracks, within walking distance from the factories. Designed for families living off blue-collar salaries, these home were small, brick, often one or two stories, and pressed closely to each other. Confined by the two CM&SP lines, families fit their homes into a tight geometric grid, creating the street structure and house design that defines Hermosa today.

During this inflow of industrial development, Hermosa residents referred to the area as ‘Garfield’ after the late president. In 1885, however, when residents wanted to establish their own post office, a Garfield office had already been taken. In order to build a new post office, they needed to rename themselves (Perry, Marilyn). Although the story behind Hermosa has been disputed, some say that Mr. Peebles, the Secretary to the Superintendent of CM&SP, suggested the name because he believed the town was beautiful and inviting, such as the Spanish translation.

Before 1889, Hermosa did not fall within the City of Chicago’s limits. Instead, it was under the Jefferson Township, a separate municipality in Cook County. Once annexed into Chicago, Hermosa grew rapidly due to City’s services and transportation system. Consequently, a slew of newcomers arrived, all seeking employment in Hermosa’s factories. Proactive real estate developers recognized Hermosa’s potential and began development in southwest Hermosa. This new patch of homes developed into Kelyvn Grove, which still neighbors Hermosa. To this day, various elements of Hermosa are named after Kelvyn Grove, including Kelvyn Park.

Possibly more catalytic to residential growth than the annexation was the development of the street car. In 1907, streetcar lines extended into Hermosa. With access to West and South Chicago, Polish, Irish and Italian families flooded the already-full neighborhood. By 1920, there were over 15,000 people living in within Hermosa’s relatively permanent boundaries (Perry, Marilyn).

By the mid 1930s, Hermosa’s population had swollen to 23,500 people, most German or Scandinavian (Perry, Marilyn). Each decade brought more Poles, Austrians and Hungarians, making Hermosa a melting pot of European migrants. Enclosed on two sides by the railroads and dead ends on the other, Hermosa inevitably cultivated community ties. Not only were residents geographically bounded, but many of their homes had 25-foot frontages. With little space between homes, I speculate that neighbors interacted regularly.

Despite Hermosa’s efficiency in production, it could not withstand America’s period of de-industrialization. As the economy globalized in the 1960s, more and more of Hermosa’s industries were either demolished or reused for store fronts and housing (Chicago Gang History). No longer in need of blue collar workers, Hermosa attracted new waves of immigrants, mostly Spanish-speaking. By the late 1960s, Puerto Ricans held the majority in Hermosa.

Unfortunately, wages dropped after the de-industrialization and Hermosa’s economy suffered. Property value declined and many affluent white families fled, bringing their wealth and resources with them. The sudden change of population caused a shift in community organization and activity. By the late 1970s, crime and gang behavior seeped into Hermosa. Residents, concerned for their safety and the future of Hermosa, soon took action (Chicago Gang History). In 1982, community members formed the United Neighbors in Action to campaign for subsidized and affordable housing (Perry, Marilyn). To hinder gang violence and affiliation, residents policed their own streets.

In the past two decades, crime and gang behavior have dropped significantly. Residents send their children to one of three Hermosa pubic schools, and can find most of their daily needs within Hermosa’s boundaries. Today, the Hermosa Neighborhood Association (HNA) gives residents the voice to advocate for better schools, services and resources. Whether because of hard boundaries or tight residents, Hermosa has always delineated itself from its surrounding communities, and thus survived the test of time. Through changes in economy, organization, ethnicity and disorder, the residents have organized themselves into a compact but malleable community.

Works Cited

Ancestry in Hermosa, Chicago, Illinois. (2017, October 7). Statistical Atlas. Retrieved from https://statisticalatlas.com

Chicago Gang History. (2017, October 9). Chicago Gang History Hermosa. Retrieved from https://chicagoganghistory.com

Hermosa. (2017, October 9). The Chicago Neighborhoods. Retrieved from http://www.thechicagoneighborhoods.com

HNA. (2017, October 9). Hermosa Neighborhood Association. Retrieved from https://www.ourhermosa.org/

Perry, Clarence A. Neighborhood and Community Planning. New York City: Regional Plan of New York and its Environs, 1929. Print.

Perry, Marilyn E. “Hermosa.” Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago: Chicago Historical Society, 2005. Web. October 10, 2017.

Schools in Hermosa. (2017, October 13).Trulia. Retrieved from https://www.trulia.com

Social Explorer. (2017, October 9). Social Explorer My Reports. Retrieved from https://www.socialexplorer.com

Source: “Hermosa.” Google Earth. October 9, 2017.

Tour of Belmont-Cragin and Hermosa. (2017, October 9). The Chain Link. Retrieved from http://www.thechainlink.org

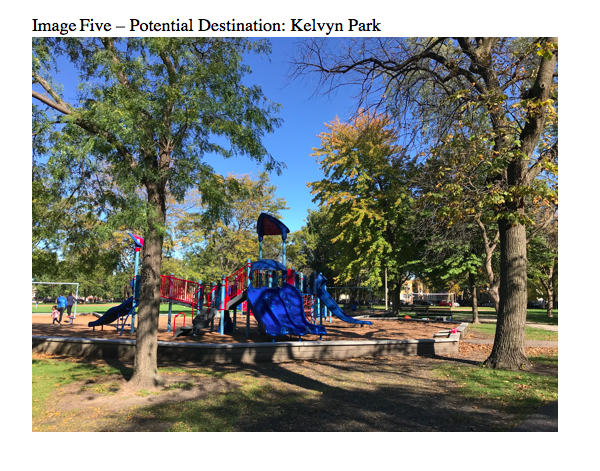

The park’s variety of public spaces and play areas attract

people of all ages. When I arrived on a Saturday afternoon, a slew of families

and children filled the playground (Image 5). Beyond the play area, a group of older

boys—middle school or junior high—kicked a soccer ball. Two others practiced

their swing on the diamond.

The park’s variety of public spaces and play areas attract

people of all ages. When I arrived on a Saturday afternoon, a slew of families

and children filled the playground (Image 5). Beyond the play area, a group of older

boys—middle school or junior high—kicked a soccer ball. Two others practiced

their swing on the diamond.

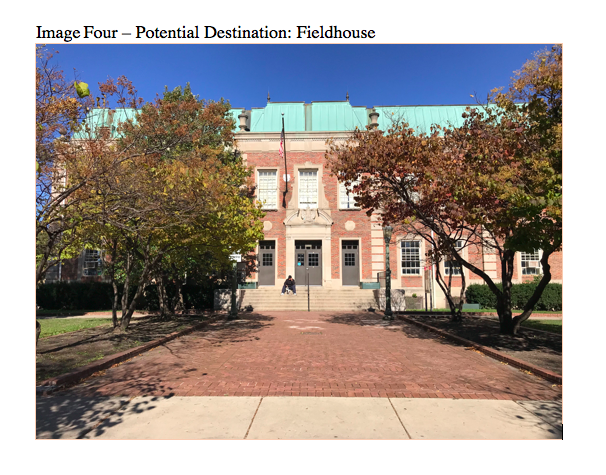

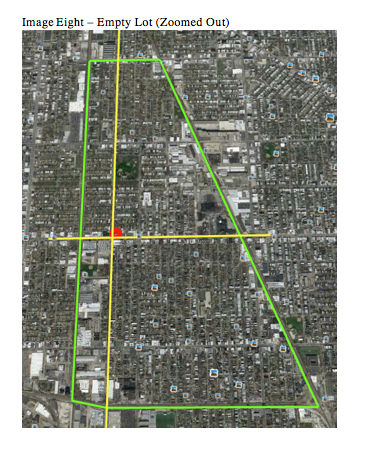

Kelvyn Park’s greatest feature might be its Fieldhouse (Image 8). Open

every day of the week, the Kelvyn Fieldhouse provides Hermosa residents with a fitness

center, auditorium, kitchen, gymnasium and open community rooms. Community

members host events, parent trainings, and other local meetings in the

Fieldhouse, and students paint their school mascots on the outside brick (Images 9 and 10).

Warn-down and well-loved, the Fieldhouse seems to anchor the park to the

neighborhood, and provide its residents with valuable services.

Kelvyn Park’s greatest feature might be its Fieldhouse (Image 8). Open

every day of the week, the Kelvyn Fieldhouse provides Hermosa residents with a fitness

center, auditorium, kitchen, gymnasium and open community rooms. Community

members host events, parent trainings, and other local meetings in the

Fieldhouse, and students paint their school mascots on the outside brick (Images 9 and 10).

Warn-down and well-loved, the Fieldhouse seems to anchor the park to the

neighborhood, and provide its residents with valuable services.

Overall, the park is very comfortable and well-kept: trimmed

grass, fresh plants, un-littered paths. Throughout the park, colorful signs

encourage community members to keep the parks clean, respect each other, and

attend elementary school events and high school theatre premiers (Images 11 and 12). Community

organizations, including the Hermosa Neighborhood Association and the Neighborhood

Watch, have made visible efforts to ensure that the park remains safe, clean

and inviting.

Overall, the park is very comfortable and well-kept: trimmed

grass, fresh plants, un-littered paths. Throughout the park, colorful signs

encourage community members to keep the parks clean, respect each other, and

attend elementary school events and high school theatre premiers (Images 11 and 12). Community

organizations, including the Hermosa Neighborhood Association and the Neighborhood

Watch, have made visible efforts to ensure that the park remains safe, clean

and inviting.

The park did, however, feel slightly off-balanced spatially.

When I visited, almost all park members used the southern half of the space, near

the play area and sports fields. Very few used the sprawling grass area (Image 13) in the

middle and north-end of the park. This uneven distribution activity might suggest

potential for a spatial redesign, or for the addition of another service or

pathway that can pull people into the unused space.

The park did, however, feel slightly off-balanced spatially.

When I visited, almost all park members used the southern half of the space, near

the play area and sports fields. Very few used the sprawling grass area (Image 13) in the

middle and north-end of the park. This uneven distribution activity might suggest

potential for a spatial redesign, or for the addition of another service or

pathway that can pull people into the unused space.

Social Mix

Below, I have organized data on Hermosa's social demographics and diversity. The Social Demographics table showcases Hermosa's age, education, housing value, housing tenure and housing type distribution. The Diversity Table dives more deeply into Hermosa's distribution of race, income and housing type, and measures each of variable on the Simpson Diversity Scale.

Below, I have organized data on the social demographics and diversity of the Northwest Region of Chicago. As for Hermosa, I included the region's age education, housing value, housing tenure and housing type.

Below, I have organized data on the social demographics and diversity of the City of Chicago. As for Hermosa, and the Northwest Region, I included the city's age education, housing value, housing tenure and housing type.

Hermosa hosts some, however not much, diversity. According to the tables above, Hermosa community members vary in age, income and education. In addition, Hermosa hosts a fairly even spread of income levels, from under $20,000 to over $150,000. Most Hermosa residents live in two, three and four bedroom homes worth about $150,000 to $299,999. Unlike the Northwest Region and the City of Chicago, Hermosa is not very diverse racially. The vast majority of its members identify as Hispanic or Latin American. Compared to the rest of the city, Hermosa is not very diverse.