Overview

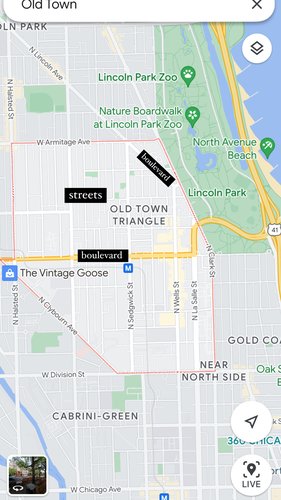

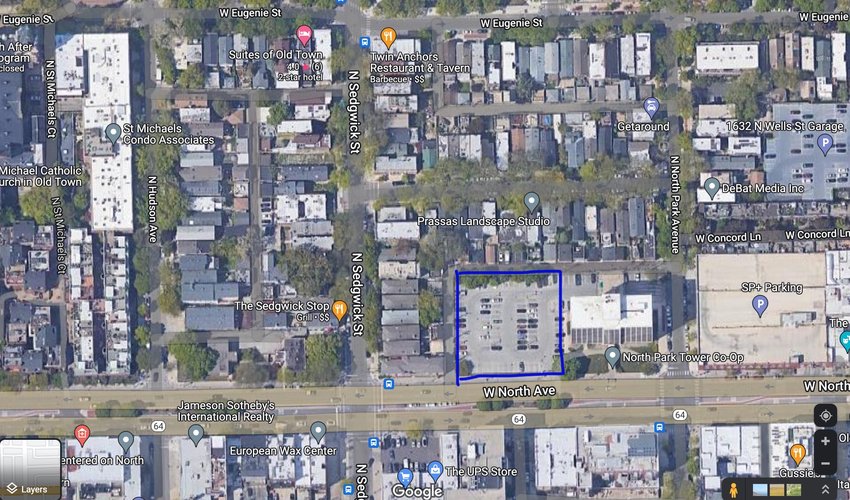

Old Town is a fairly large neighborhood when the full possible extent of its boundaries are considered. Despite this, the neighborhood does seem to have a unified identity. However, I suspect that there are also sub-neighborhoods within this larger geographic area, which I hope to explore further in future assignments. One interesting point is that Google Maps shows a portion of the city as belonging to both Old Town and Lincoln Park, so the boundary between these two neighborhoods could be evaluated further.

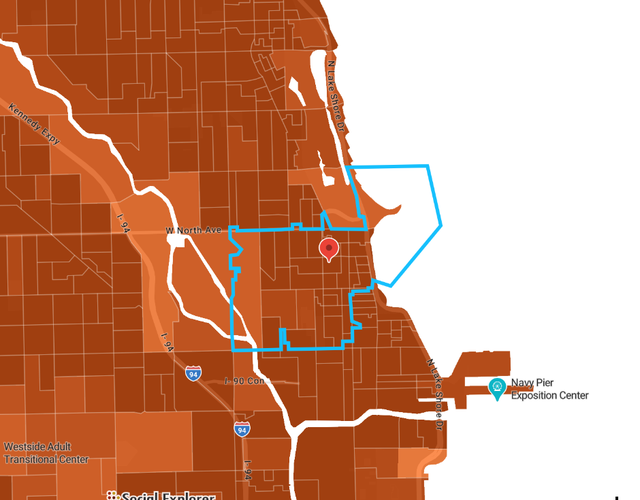

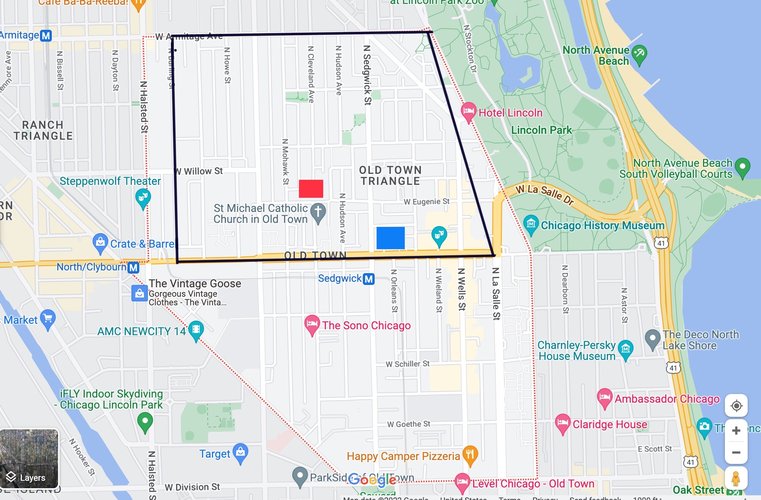

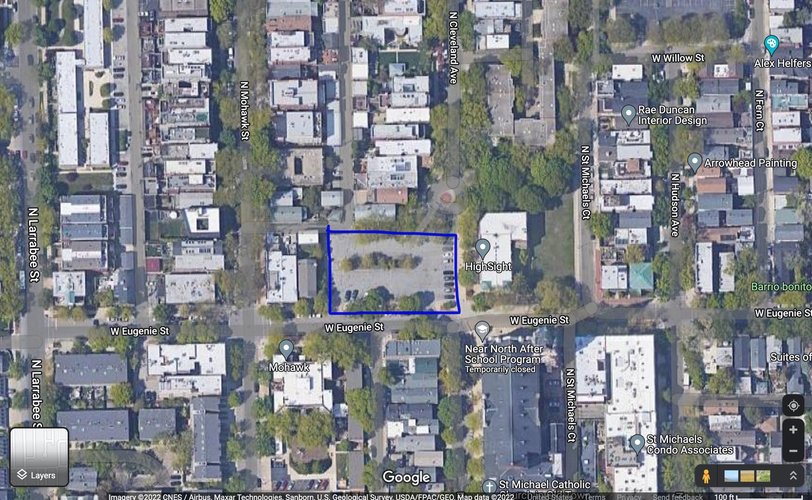

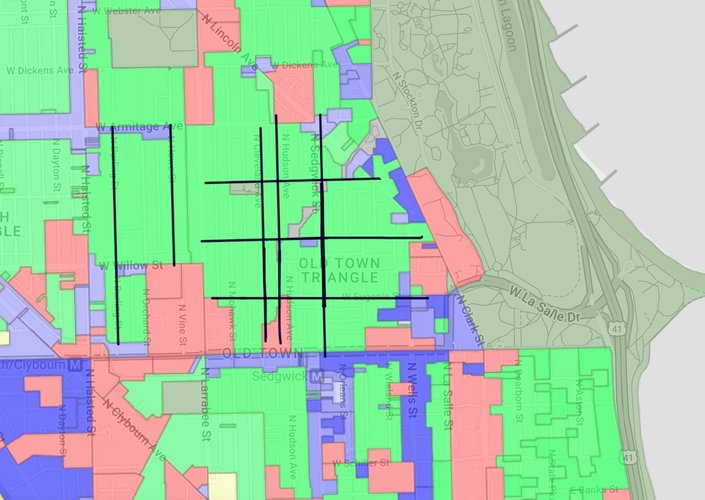

To estimate the population of Old Town, I used the social explorer tool and counted the population by census district. I counted approximately 16,800 people living in the 60610 zip code area of Old Town and approximately 13,100 people living in the 60614 zip code area. In total, I am estimating the population of the entire Old Town area to be about 29,900 people. This is much larger than Perry’s ideal 5000 person neighborhood, suggesting that there are likely many smaller communities within the larger area of Old Town. Another consideration is that some people identify the “Old Town Triangle” as the key geographic area of the neighborhood, while areas around this triangle could be classified as other neighborhoods.

The image below shows how I found the zip codes that make up Old Town in Social Explorer. I then hovered over each delineated census tract and added up the population in each census tract for the sections of the 60610 and 60614 zip codes that are identified as being part of Old Town.

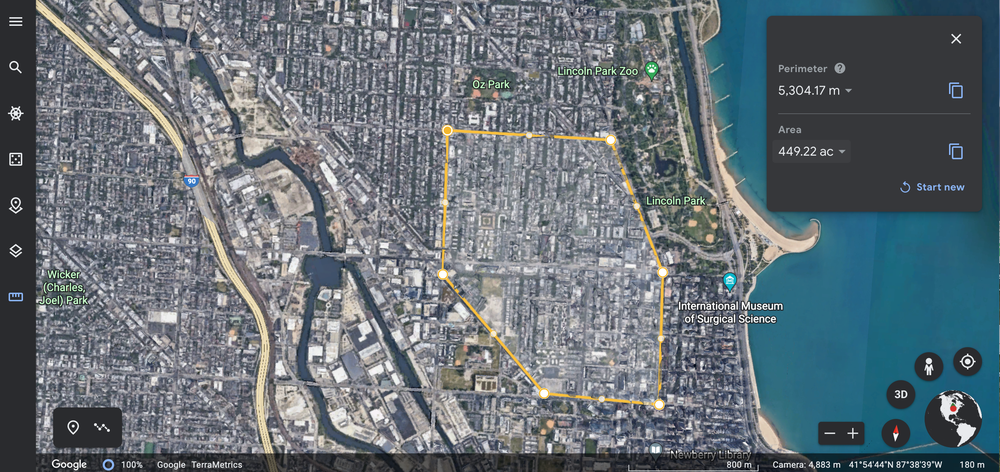

To estimate the size of Old Town, I drew the boundaries (as stated by Google Maps) in Google Earth to calculate the land area. Google Earth determined that the area inside these boundaries is 1.82 km2, 0.7 mi2, and 449.22 acres.

Based on my experience exploring the neighborhood of Old Town, I believe the area has a distinct sense of identity. This was evident through physical markers and shop signs. The most clear indication of Old Town’s identity and delineation was the installation of several large archways that serve as a sort of welcome gateway into the neighborhood. I saw six of these gateways during my time in Old Town, and three are pictured below. Their wrought iron material and design calls on the neighborhood’s identity as an area with significant history and historical significance. The openness of the gateways, rather than being actual physical gates, helps to prevent a suggestion of exclusion.

Another indication of the neighborhood’s identity were the historical placards located along Wells St, the main commercial street in the neighborhood. These plaques described important historical events that had taken place in Old Town and detailed the area’s development since its first settlement. The presence of these informational pieces suggests a sense of local identity and identification with the place’s history.

A third indication of Old Town’s neighborhood identity is the names of businesses in the area. The below photo shows the Old Town Barbershop and the Old Town Pub located next door to one another. These are certainly not the only local businesses that identify themselves as being located in Old Town. The Old Town Ale House, for example, has been a neighborhood dive bar since 1958 and continues to encourage a sense of identity among the local community

Lastly, I want to highlight the Old Town Triangle Association (OTTA) which has a visible and strong presence in the neighborhood. Such a strong neighborhood association also points to there being a strong sense of local identity, at least within the Old Town Triangle section of the neighborhood (a delineation which has been expanded from its original boundaries by the OTTA, and is no longer triangular shaped, but still does not include the entirety of what Google Maps says is Old Town). When I was walking through the neighborhood, I saw multiple art installations that were sponsored by the OTTA. I have included a photo of one of these installations as well as the accompanying plaque that names the OTTA as the sponsor.

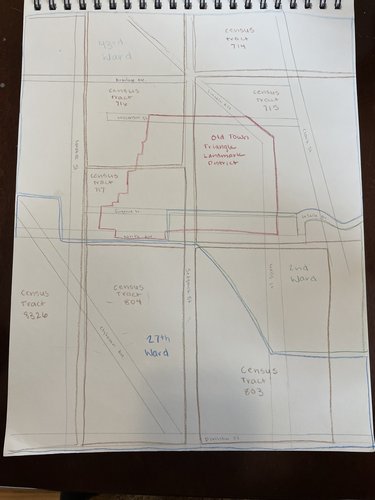

Parts of Old Town exist in three different aldermanic wards and six different census tracts. The Old Town Triangle Landmark District marks the boundaries of what is considered the “Old Town Triangle” as well as the boundaries for the Old Town Triangle Association, the most prominent neighborhood governance group in this area. All of Old Town sits in the 18th police district.

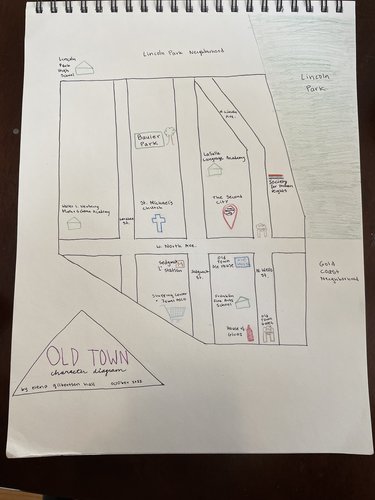

This character diagram of Old Town highlights many of the key locations in the neighborhood. The major schools in the area are marked by green building drawings. The Second City Comedy theater is one of the most famous locations in Old Town and is represented on this map by a representation of its iconic sign on North Ave. A few important community landmarks are shown on the map, including the Sedgwick ‘L’ station which, constructed in 1900, is one of the oldest standing ‘L’ stations. The stop serves the brown and purple CTA lines. Also highlighted are Bauler Park and the shopping center at the intersection of Sedgwick St., Clybourn Ave., and Division St., which serves much of the area as a major shopping location for groceries and other needs.

St. Michael’s Church is one of the most notable historical buildings in the area, and it is represented by a cross at its location between Larrabee St. and Sedgwick St. The original location of the Society for Human Rights (the first gay rights organization in the US) is highlighted with a gay pride flag alongside Wells St.

House of Glunz is the city’s oldest wine merchant and has operated in Old Town since 1888. The Old Town Ale House has been in operation since 1958 and is an essential neighborhood landmark. Other notable locations include Lincoln Park, which constitutes an eastern boundary, and the gateways lining Wells St. that welcome visitors to the neighborhood.

The land now known as Old Town was originally inhabited by Indigenous peoples of the Potawatomi, Miami, and Illinois tribes. Most of these Indigenous people were forcibly removed after the 1833 Treaty of Chicago, and Old Town was primarily settled by German immigrants in the 1850s. These immigrants primarily farmed crops such as potatoes and cabbage, which was the origin of Old Town’s nickname “The Cabbage Patch” (Town Square Publications). Over time, Old Town evolved from an agricultural area to a hotspot of commercial and cultural activity.

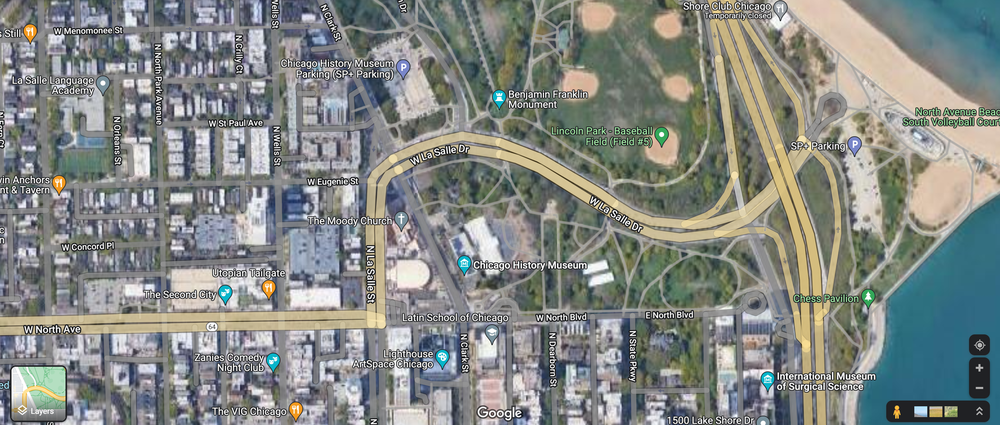

It seems that this neighborhood was not deliberately “planned”. Many of the streets, particularly in the central “Old Town Triangle” area were formed before the Chicago Fire and do not conform with the classic gridded street pattern. Old Town was not originally a part of the city of Chicago, but was annexed in 1851. Since then, it has undergone developments and “renewal” that have perhaps been a sort of retroactive planning, but the area does not seem to have originally been intentionally designed.

In the 1920s, Old Town became a center of arts and culture in Chicago, which continued on through the 20th century. Three primary examples of this are the Old Town Holiday art fair, the Old Town School of Folk Music, and the Second City comedy club.

The “Old Town Holiday” is an art fair that was started by a group of artists in 1950. Many people cite this as the origin of the Old Town neighborhood name, which stuck after the year had been going on for many years. The Old Town Art Fair still happens today and is one of two major art fairs in the neighborhood.

In 1957 a group of folk musicians founded the Old Town School of Folk Music. This school went on to bring many major musicians to the neighborhood such as Bob Gibson and Bonnie Kolac (Town Square Publications). In addition to this institution, Old Town was a center for music and all forms of counterculture during the mid 20th century.

The Second City, one of the world’s most prolific comedy theaters, was founded in Old Town in 1959. The Second City serves as a major cultural center for the city of Chicago and a key entertainment center for the neighborhood. The theater has been a launching point for many prominent actors and comedians such as Steve Carrell, Tina Fey, Amy Poehler, Jordan Peele, and Stephen Colbert (The Second City).

Old Town has historically been an important location for LGBT Chicagoans, although that identity of the neighborhood has dwindled in recent years. In 1924, Henry Gerber founded the first gay rights organization in American history, known as the Society for Human Rights, in Old Town (National Park Service). Gerber’s home in Old Town is now a National Historic Landmark. In the decades following Gerber’s activism, Old Town became perhaps the first widely known LGBT neighborhood in the city. Wells Street, the main commercial street in Old Town, was lined by many gay bars and other LGBT-friendly establishments. However, as the area gentrified and rent prices dramatically increased, most LGBT businesses and many residents were pushed further north to the Lake View neighborhoods (Wikipedia). All of the gay bars on Wells Street had closed as of 2013.

Although originally dominated by German immigrants, the Old Town neighborhood gradually became more diverse. In the 1950s and 60s, the area saw a significant number of Puerto Rican immigrants move into the area (Newhart, 2016). More recently, as prices have risen and gentrification has accelerated, the diversity has again declined and become more homogeneously white and higher income.

During World War II, a civil defense map highlighted the boundaries of North Avenue, Clark Street, and Ogden, leading the neighborhood to be called the “Old Town Triangle” because these three streets created a triangle shape. This triangular region was designated a neighborhood defense unit during the war, creating a spirit of association and solidarity (Encyclopedia of Chicago). Following the war, the area became known as “North Town” and then “Old Town” after the creation of the Old Town Holiday market (Town Square Publications).

The St Michael's Catholic Church was built by Old Town’s German settlers in 1852. Throughout history, this location has served in many ways as a neighborhood center. In 1967, Donna Gill wrote in a Chicago Tribune article: “... it was said that all who lived within hearing distance of the church's bells were Old Towners” (Chicago Tribune). This church was one of less than ten buildings known to have survived the Great Chicago Fire in 1871 (Rumore and Cassella, 2021).

Resources

Chicago Tribune (Rumore and Cassella): https://www.chicagotribune.com/history/great-chicago-fire/ct-great-chicago-fire-buildings-that-survived-20210928-rgxpmogysfdivecjq2b67erz7e-story.html

Culture Trip: https://theculturetrip.com/north-america/usa/illinois/articles/a-brief-history-of-puerto-ricans-in-chicago/

Encyclopedia of Chicago: http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/927.html

National Park Service:

The Second City: https://www.secondcity.com/people/alumni/

Town Square Publications: https://townsquarepublications.com/history-of-old-town-chicago/

Social Mix

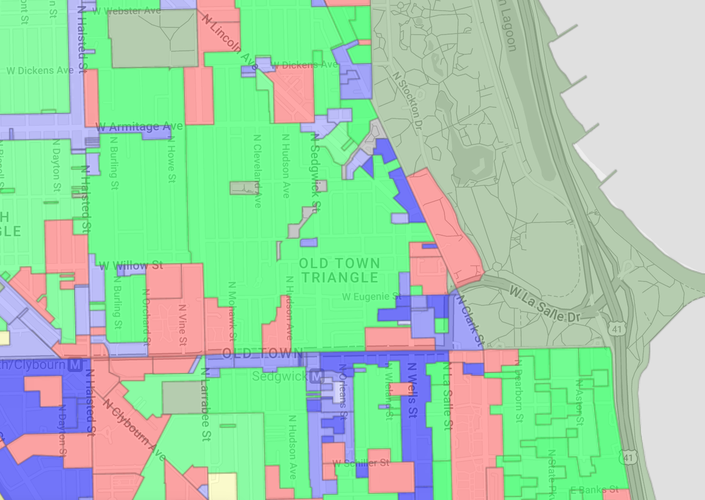

Conducting the Simpson Diversity Index calculations was very illuminating. It is clear that the Old Town neighborhood is less diverse than the city of Chicago, as well as the North Region of Chicago, on these three variables. The neighborhood has slightly more education and age diversity than its broader community area, but in every other category and area it is less diverse than those it is compared with. The neighborhood does have a fairly high level of age diversity that is not dramatically different from the other scales of observation. However, I think the breakdown of age categories is slightly different in this neighborhood because a plurality of residents (about 42%) fall into the 18-34 age range. This suggests a slightly younger average age compared to the broader city. I did not use income as one of my variables for the Simpson Index, but it is clear from looking at the initial demographic table that Old Town is very skewed towards high income residents. Nearly 60% of households are earning over $100,000, and when the data is broken down further, 27% of households are earning over $200,000. This neighborhood is not particularly income diverse, although it does have higher income diversity than racial diversity (2.63 index with 5 categories compared to 1.76 with 6 categories).

Overall, I would not describe Old Town as diverse. It is predominantly white, high income, and fairly highly educated. The variable I calculated that demonstrates the highest level of diversity in this neighborhood is age. However, even in the age category, it is less diverse than its region and the city as a whole. The most striking observation to me is the race diversity score of 1.76 compared to Chicago’s 3.04. The table shows that the Old Town neighborhood, Lincoln Park community area, and North region are all much less racially diverse than the broader city.