Overview

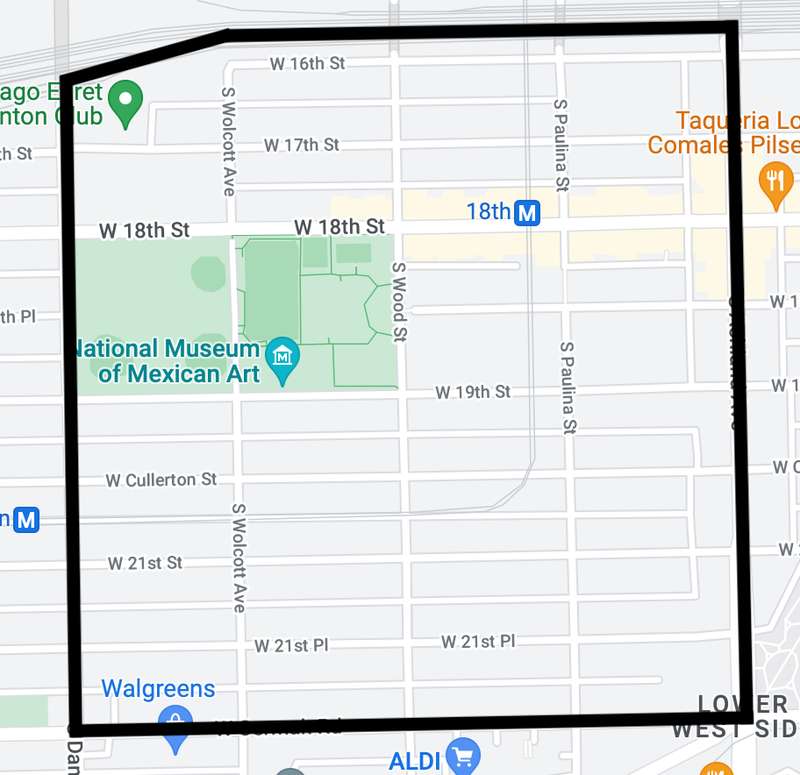

Size

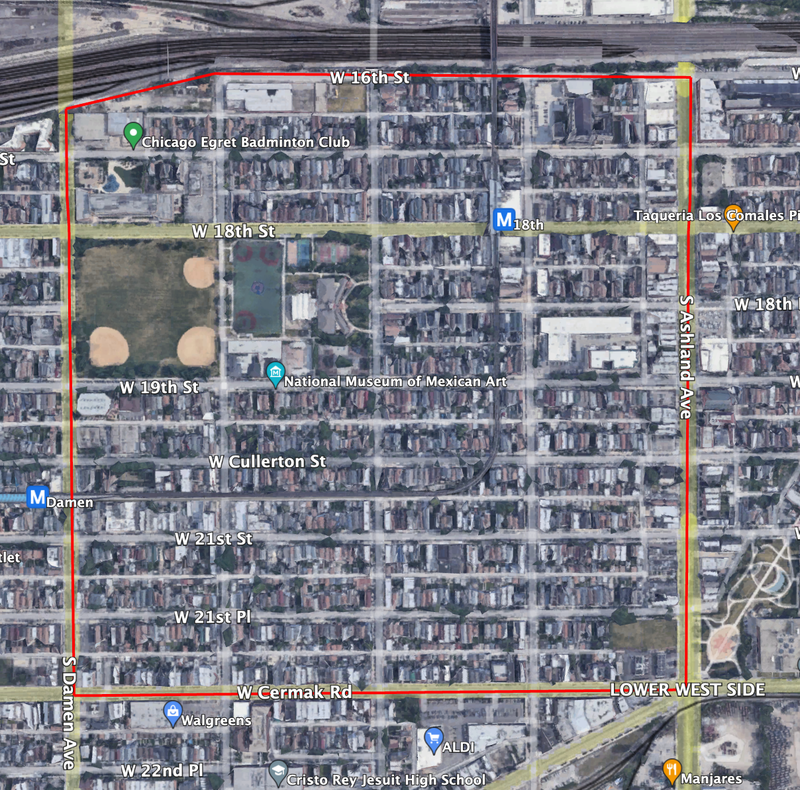

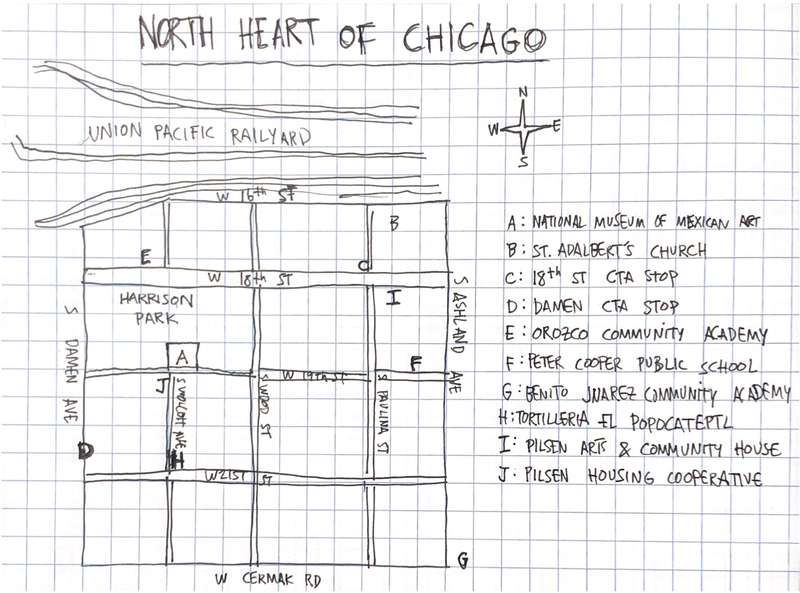

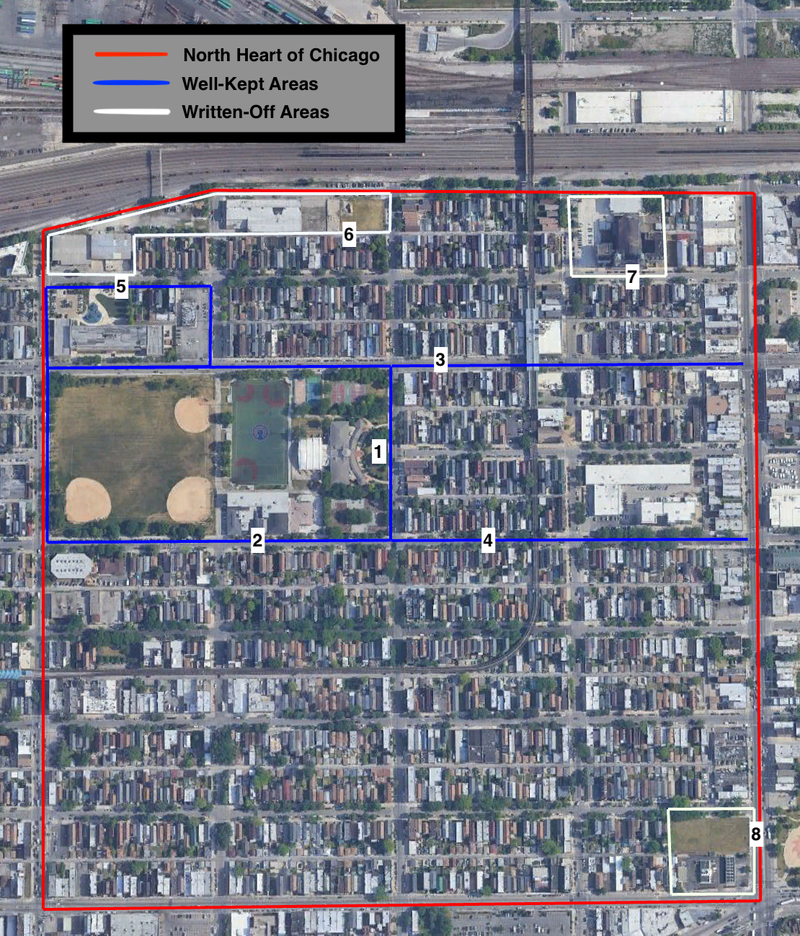

North Heart of Chicago, a subdivision of the larger Heart of Chicago neighborhood, extends from Damen Avenue on the west to Ashland Avenue on the east, and from Cermak Road on the south to the Union Pacific Railyard on the north. Per Social Explorer, it holds a population of approximately 7,422 people, making it somewhat larger than a big high school. North Heart of Chicago comprises the densest and most commercially active portion of the broader neighborhood. The neighborhood has an area of 160 acres (about 0.5 miles on each side), making it very walkable.

Identity

North Heart of Chicago feels, in many ways, like an extension of Pilsen. Though Ashland Avenue ostensibly demarcates the two neighborhoods, the strong Mexican identity that characterizes Pilsen is just as visible, if not more, throughout its western sibling. Indeed, North Heart of Chicago residents and businesses seem to view themselves more as part of a ‘Greater Pilsen’ than a separate neighborhood. Even several blocks west of Ashland, businesses use ‘Pilsen’ as the geographic identifier in their name: Pilsen Housing Cooperative, Pilsen Dental, Pilsen Body Shop. Farther south and west, in the area abutting Heart of Italy, Heart of Chicago assumes a more distinct identity–still decidedly Mexican, but inflected withItalian-American flavor (as evidenced by the presence of various red-sauce joints) and more willing to distinguish itself from Pilsen. The membrane between Pilsen and Heart of Chicago is porous and difficult to define confidently, but North Heart of Chicago undoubtedly leans more towards Pilsen.

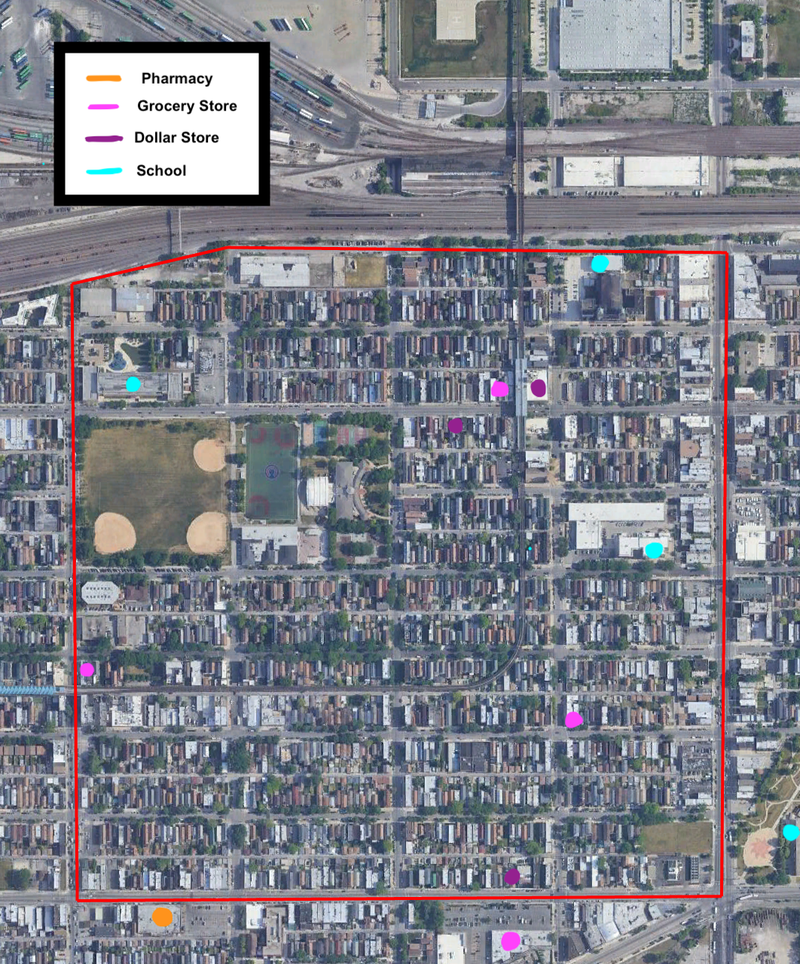

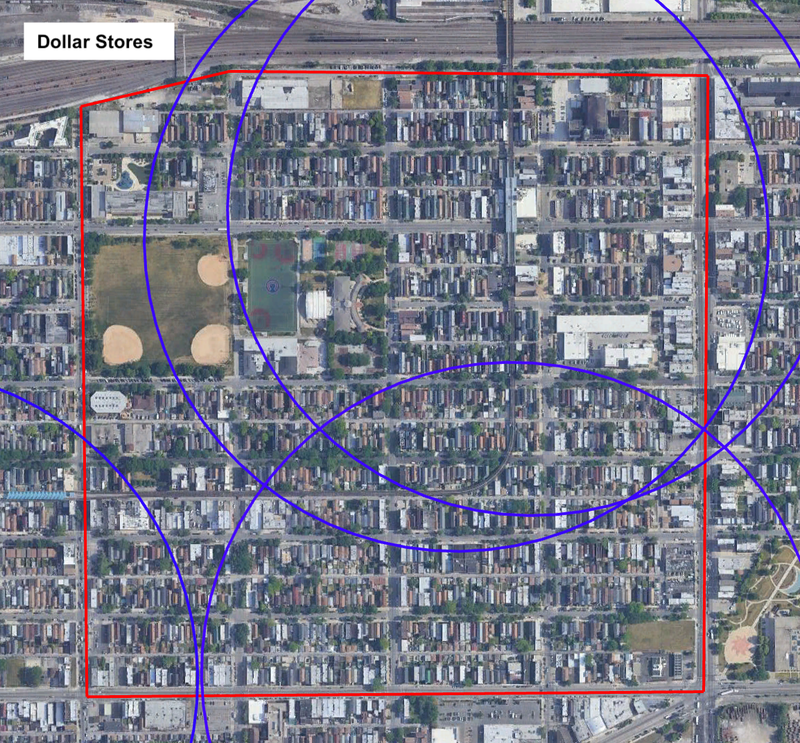

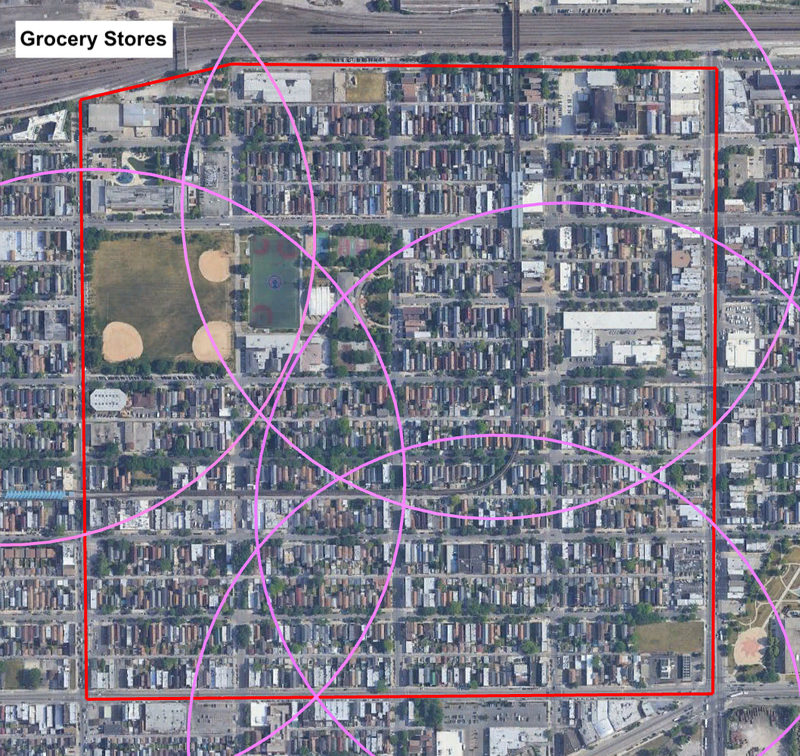

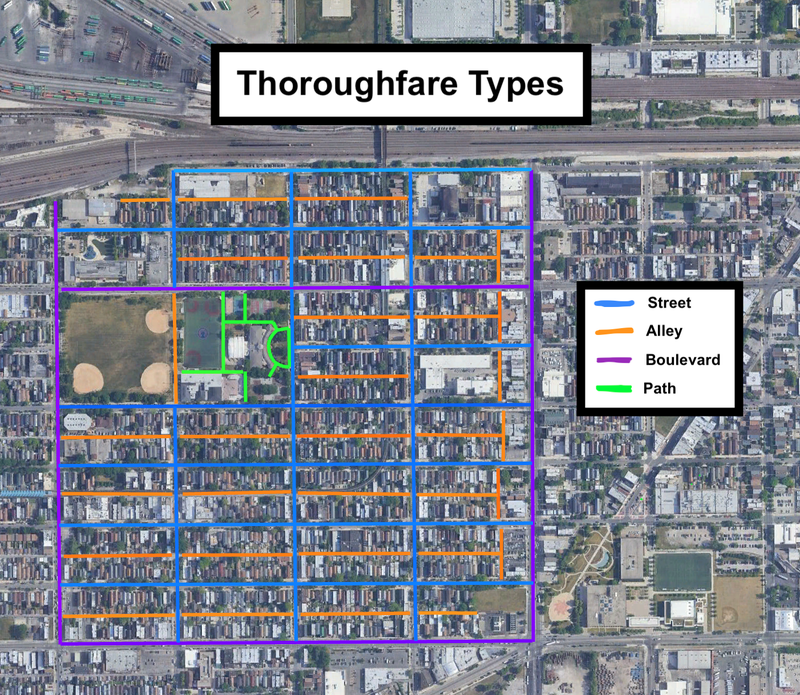

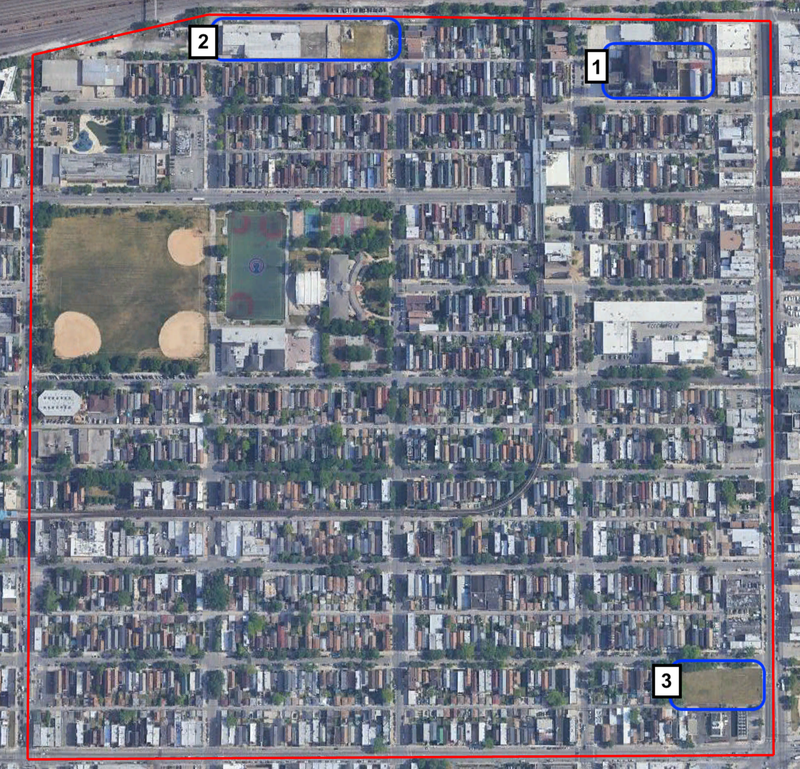

18th Street (particularly between Ashland and Wood St) constitutes the primary pedestrian commercial thoroughfare of North Heart of Chicago. Colorful signs advertising taquerías, bookstores, and cafés dot the street’s two- and three-story buildings. Harrison Park anchors the neighborhood. At 18.6 acres, the park serves as the main ‘third place’ in North Heart of Chicago; a soccer field and baseball diamonds occupy the western half of the park, while the eastern half is divided between a turf field, basketball courts, a fitness center, a playground, and the National Museum of Mexican Art. South of the park, the neighborhood is almost entirely residential and unmistakably Mexican; more than any other flag, green, white, and red tricolors hold watch over the porches of the duplexes and single-family homes that fill these streets. As in Pilsen, street art and murals constitute an integral part of the neighborhood’s aesthetics.

Even farther south, near and past Cermak Rd, the area is pockmarked by empty parcels and parking lots. There, the neighborhood sheds some of its residential character and adopts a more industrial personality. On the far southeast corner of the neighborhood, the courtyard of Benito Juarez Community Academy is adorned with iron statues of Mexican national heroes: the likenesses of Cuauhtémoc, Francisco Madero, and Emiliano Zapata, among others, illustrate how tightly Mexican history is woven into the social fabric of the Heart of Chicago.

Layers

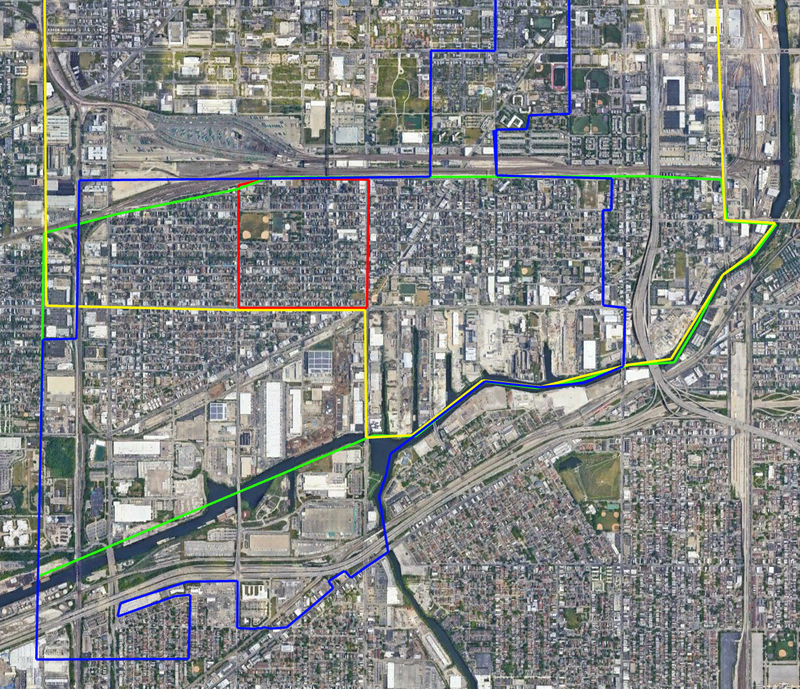

North Heart of Chicago (outlined in red) is part of the Lower West Side community area (outlined in green), Chicago police district 12 (outlined in yellow) and Ward 25 (outlined in blue). It is a full part of all these layers (and it should be noted that it remains whole within all other political subdivisions – i.e. Congressional District 7, State Senate District 1, and State House District 2 (all of these districts have substantial Latino populations). While Heart of Chicago as a whole is not entirely kept together in some of these layers (e.g. police district) the North Heart of Chicago sub-neighborhood, emphasizing its cohesiveness as a city subdivision with a population closer to that prescribed by Clarence Perry.

Diagram

History

It is difficult to recount the history of Heart of Chicago without accounting for how it is intertwined with that of Pilsen and the Lower West Side at large. German and Irish immigrants settled the neighborhoods first. Many of them worked on the Illinois Michigan Canal, while others were enticed by the Southwestern Plank Road, which eased trade routes along the canal. The Great Chicago Fire of 1871 displaced a large portion of the immigrants from Bohemia (now the Czech Republic) living in Chicago, leading many of them to resettle in the Lower West Side. Most of the Bohemians moved to what is now Pilsen (the name derives from a popular restaurant named after the Bohemian city of Plzeň). The opening of McCormick Reaper Works in South Lawndale in 1873 created many new jobs for residents of the Lower West Side and imparted the then-industrial town with a strong working class identity.

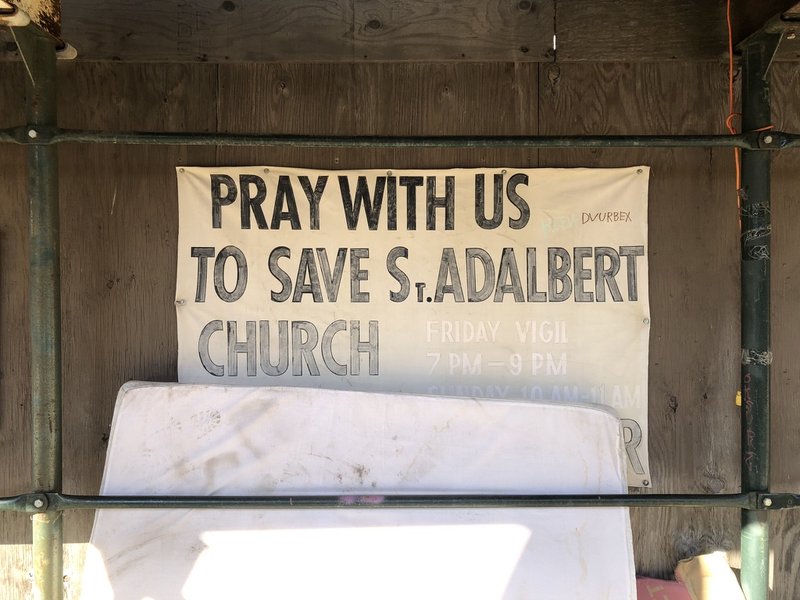

The distinction between Pilsen and Heart of Chicago first arose during the final decades of the 19th century. Heart of Chicago was more affluent than Pilsen, retained more of the original Irish and German population, and became largely Polish (with a non-trivial amount of Italian immigration, as well), while Pilsen remained poorer and predominantly Bohemian. Indeed, many better-off Bohemians from Pilsen moved to Heart of Chicago and South Lawndale as they became wealthier, buying property in these more desirable areas. During these decades, Polish immigrants established many of their own ethnic neighborhood institutions: (Catholic) churches, schools, newspapers, and so forth. Some vestiges of Polish identity persist even today: for instance, the facade of St. Adalbert’s Church, which was founded in 1874 to serve the Polish Catholic community, presents three open-air shrines, one featuring Mary hemmed in by American flags, another the Virgin of Guadalupe encircled by Mexican flags, and the third St. Adalbert of Prague surrounded by Polish flags.

The Lower West Side was annexed into the city of Chicago in 1889, paving the way for increased prosperity as the neighborhood gained access to the city’s ability to pave roads and its mass transit system. In the first decades of the 20th century, Heart of Chicago remained a major manufacturing center with a strong industrial character. However, the Great Depression and WWII undermined the neighborhood’s stability; when various plants in and around Heart of Chicago, including International Harvester, shuttered during the Depression and post-war, many of the neighborhood’s working class residents moved away, the economic cornerstone of the area having been broken. Between 1930 and 1960, the population of the Lower West Side as a whole decreased from 66,198 to 48,448–a nearly 27% drop.

The completion of the Stevenson Expressway (part of I-55) in 1964, helped spur the revitalization of the Lower West Side by connecting it to the Loop and other job-rich parts of Chicago. Between 1960 and 1970, the first wave of Mexican in-migration came to Pilsen and Heart of Chicago, and by the end of the decade, Mexicans comprised a majority of the neighborhoods’ population. The completion of UIC’s campus in the Near West Side (where many Mexican families lived) in the early 1960s impelled westward migration to the Lower West Side. In the ensuing years, an even greater number of Mexicans (and, to a lesser extent, Puerto Ricans) living primarily in the American southwest moved to Heart of Chicago and Pilsen, to the point where in 1990, 88.1% of Lower West Side residents were Latino (compared to less than 0.3% in 1960). As the Mexican population ballooned, residents refashioned the neighborhood institutions once dominated by white ethnic groups to reflect the area’s new composition. Catholic parishes opened for Polish immigrants began to cater to Mexicans, Mexican artists filled the neighborhood with flamboyant murals, Benito Juarez Community Academy (mentioned earlier) opened, Spanish-language newspapers began to circulate, and so forth: the ethnic transition was complete.

Heart of Chicago's original raison d’etre was manufacturing, providing a residential area near various industrial plants on what is now the West Side. Its proximity to the Union Pacific railyard further cemented the accessibility of employment opportunities. The neighborhood today does not particularly resemble the one that arose during the 19th century: Harrison Park was opened in 1912, most manufacturing plants had closed by 1960, and urban renewal had entirely altered the neighborhood landscape by 1970. Nevertheless, what has remained consistent in Heart of Chicago’s identity is its status as a point of entry for working class immigrants, originally from Europe, today from Mexico and the rest of Latin America.

Sources

ABC7Chicago: https://abc7chicago.com/pilsen-chicago-history-neighborhood-gentrification/12312130/

City of Chicago Data Portal: https://data.cityofchicago.org/Public-Safety/Boundaries-Police-Districts-current-/fthy-xz3r

Chicago Encyclopedia: http://encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/765.html

Chicago Gang History: https://www.chicagoganghistory.com/neighborhood/lower-west-side-heart-of-chicago/

Illinois Policy: https://www.illinoispolicy.org/maps/

Social Explorer: https://www.socialexplorer.com/a9676d974c/explore

Social Mix

Using the Simpson Diversity Index, I calculated the diversity of North Heart of Chicago with respect to three variables: race, educational attainment, and housing type. The corresponding indices for the Lower West Side (the community area within which Heart of Chicago resides), the West Side, and the city of Chicago as a whole are included to facilitate comparative analysis.

Relative to these other geographical subdivisions, North Heart of Chicago is less diverse with respect to all three selected variables. Its low racial diversity index (1.64) is a function of the neighborhood's heavily Hispanic population (more than 3/4 of residents self-identify as Hispanic). The Lower West Side as a whole is slightly more racially diverse, but is similarly disproportionately Hispanic. In contrast, the West Side and Chicago as a whole have substantially higher racial diversity indices (of course, the index does not account for the high level of racial segregation that exists in Chicago). When it comes to educational attainment, however, North Heart of Chicago appears to be more representative of the city. Its index of 4.76 more closely approximates the city's index of 5.17. It is relevant to note that the composition of educational attainment is not the same as the city; a plurality (28.2%) of North Heart of Chicago residents have not completed a high school education, compared to 14.1% of Chicagoans. This disparity is likely due to the high proportion of recent Latin American immigrants that live in the neighborhood, who have not had the opportunity to complete a secondary education in their home country or to pursue equivalency in the U.S. Finally, North Heart of Chicago has a less diverse mix of housing types than the other relevant subdivisions. Indeed, a vast majority (83.0%) of units in the neighborhood are in buildings with 2 to 9 units. As nearly 70% of neighborhood residents are renters, this sort of distribution makes sense, with most people living in apartments or duplexes. The city and the West Side have significantly higher proportions of single-family homes and buildings with more than 50 units.

On the whole, North Heart of Chicago is not particularly diverse, especially with respect to the primary variable that comes to people's minds when referring to diversity: race. The population is overwhelming Hispanic (Mexican, to be precise), and proportionally less diverse than its community area, region, and city. Though more diverse with respect to education and housing type, the neighborhood is not especially diverse on either of those metrics either. Given these variables, it is quite easy to imagine the modal North Heart of Chicago resident: a Hispanic person who lives in a four-flat and either has no high school degree or has a bachelor's degree.