Overview

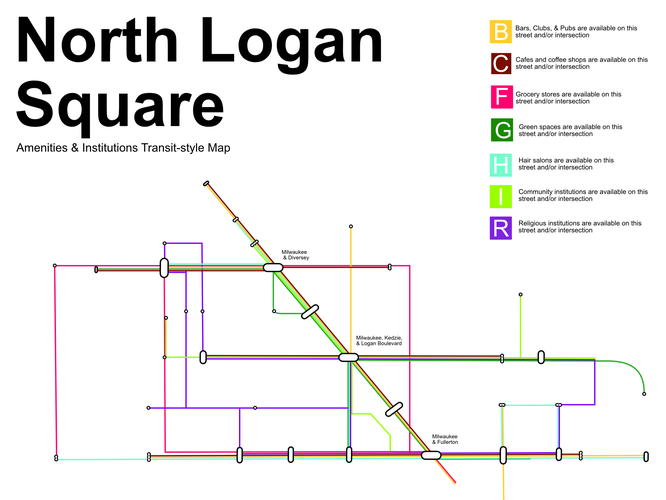

Overview, Size, Layers & Illustrations

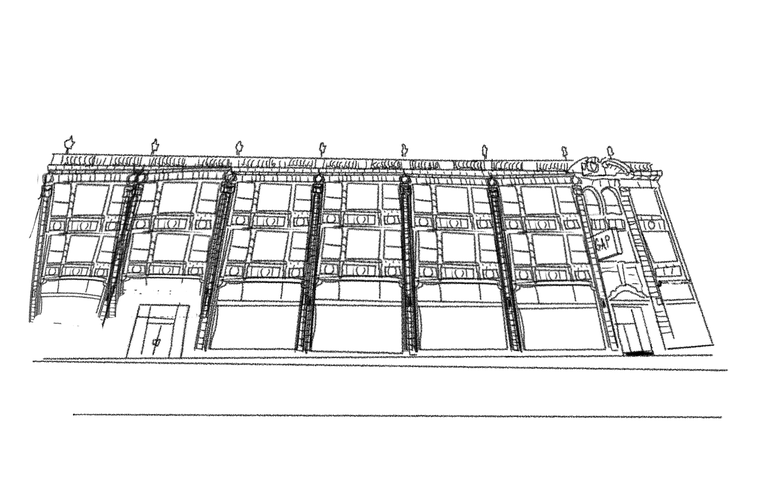

Featured Image Description: Logan Theater on Milwaukee Avenue, north of the Illinois Centennial Monument, located in the actual Logan Square. Photo taken October 29, 2022 by Micah Wilcox.

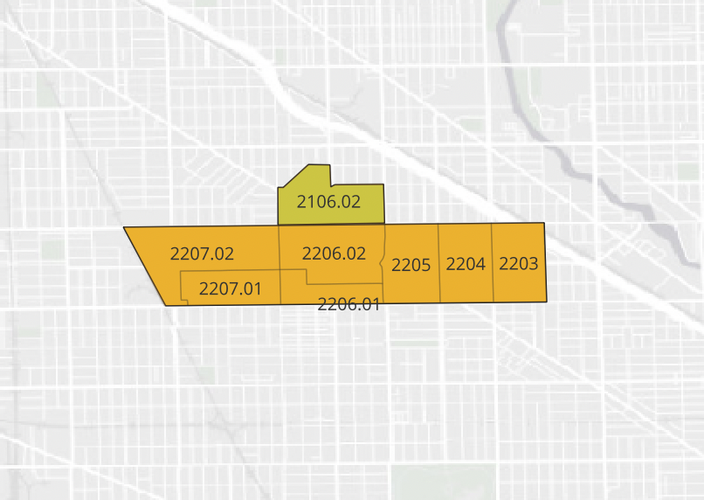

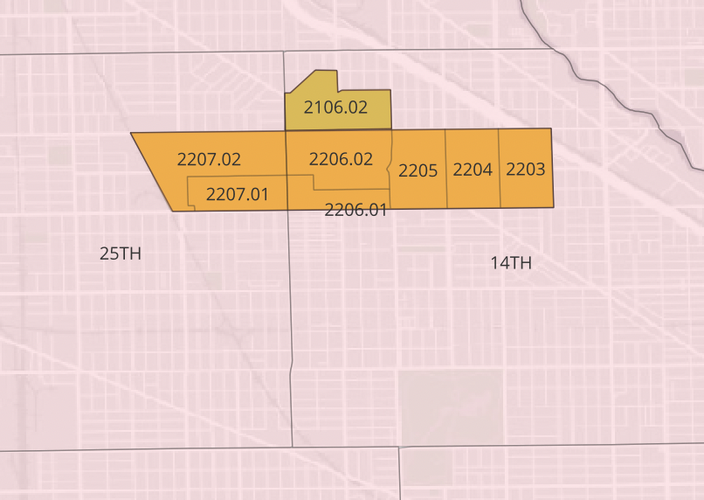

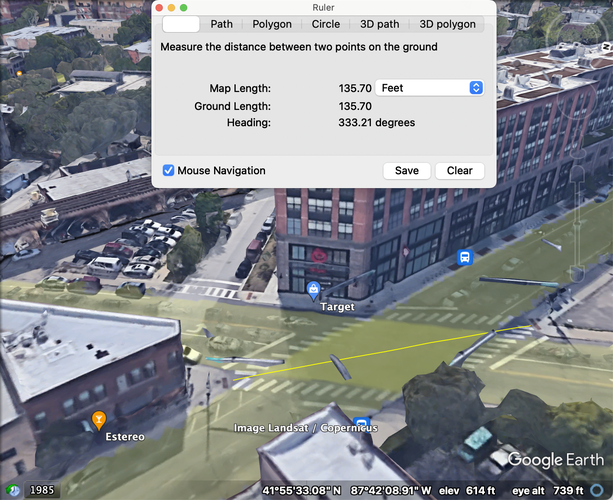

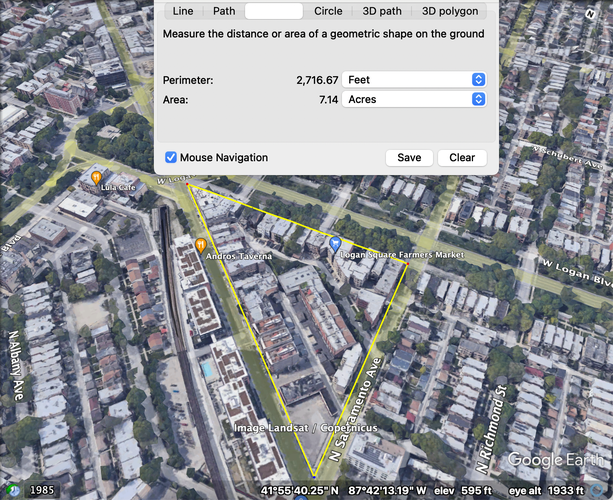

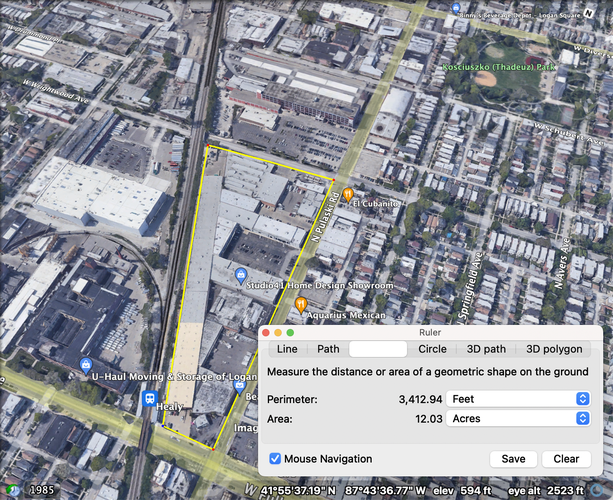

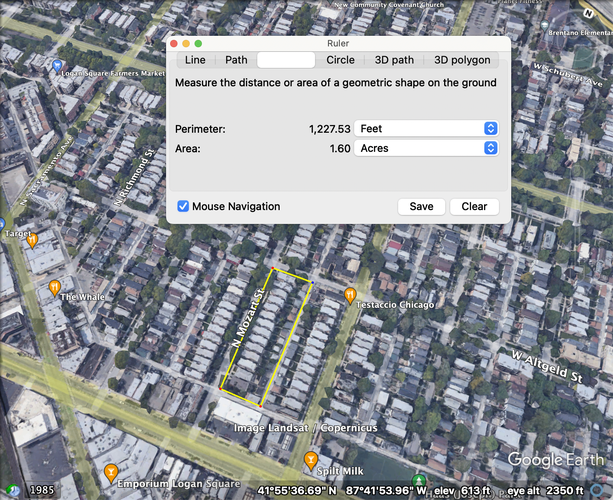

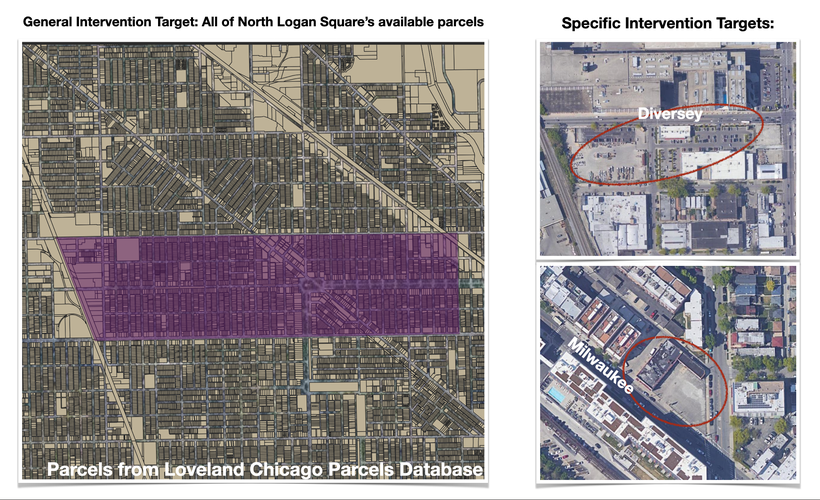

Officially (per the Zolk Google Map), North Logan Square is 0.96 square miles, including in their entirety the census tracts between Diversey, Fullerton, the Metra Milwaukee District-North route, and, for the purpose of this project, I-90/Rockwell (Western Avenue, which Zolk uses as their border, is in the middle of a large census tract that hugs the north branch of Chicago River). However, including Tract 2106.02 – a borderlands area between Logan Square and Avondale that sports the Solidarity Triangle, a park maintained by the Logan Square Chamber of Commerce and the Milwaukee Avenue Alliance, and the headquarters of the Logan Square Neighborhood Association/Palenque (LSNA/Palenque), results in a total area of 1.11 square miles. Note: although I discuss Tract 2106.02 in Overview and Social Mix, I do not include it in my analysis of Public Space, Amenities, or Connectivity, nor is it considered part of North Logan Square in my Final Project.

The population of the core area is 20,622, but with the tract north of Diversey, the population rises to 24,770. These counts reflect Logan Square’s highly dense built form, a form that goes back to its early organization pre-Chicago annexation in 1889. Although the neighborhood is far larger than Jane Jacobs’ conception of “face streets,” North Logan Square is oriented around major street corridors: Milwaukee Avenue (Northwest), Diversey, and Fullerton (East-West). Diversey and Fullerton serve as the streets in the spirit of Talen's conception of “seams" or unifiers between neighborhoods (Neighborhood 2019, 93-95). Fullerton serves as the boundary with South Logan Square and Palmer Square, which is fully surrounded by North and South Logan Square. Diversey serves as the border with Avondale. This concept of “seam” is especially relevant to Diversey, given that Avondale is more distinctly “separate” from North Logan Square than South Logan Square. The “seam” nature of the street – i.e. its operation as a joining force rather than a dividing barrier – is accentuated by the fact that the Logan Square Neighborhood Association (Palenque)’s headquarters is just north of Diversey. On the intersection of Milwaukee and Diversey – just down the block – one can find the Solidarity Triangle, the Logan Square Chamber of Commerce-maintained park whose website declares it “a plaza for the people at the gateway to Chicago’s Avondale neighborhood.”

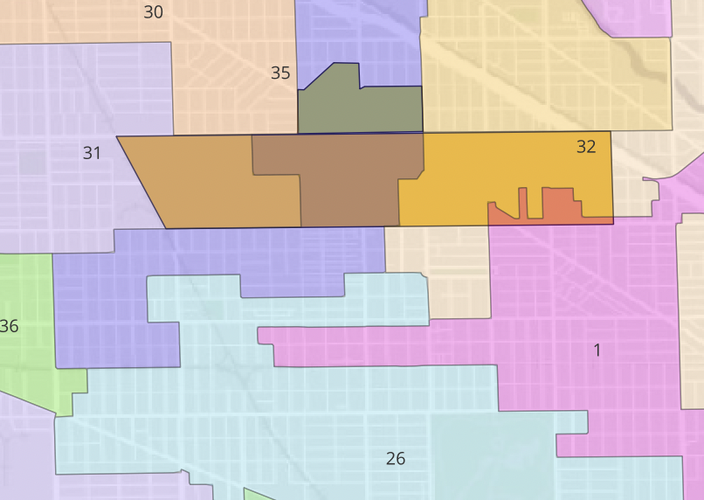

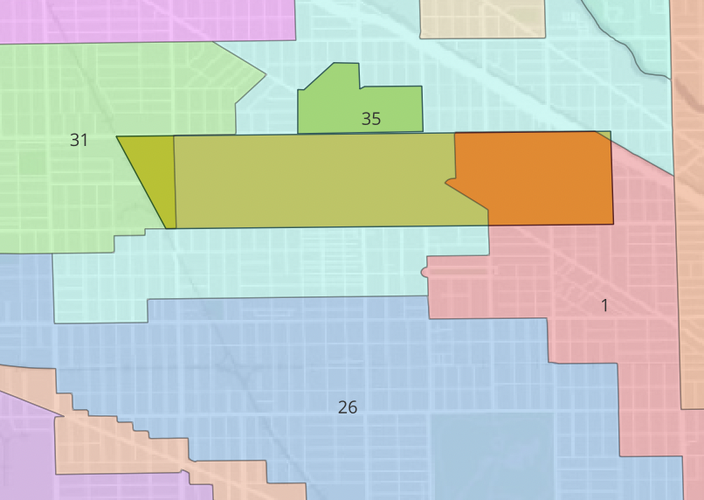

North Logan Square is split into two parts for police precincts and Ward districts. From Albany to Milwaukee to North Sacramento, North Logan Square is divided everything west of those boundaries is in the 1st District, while the rest – including Tract 2106.02 – are in District 35. This represents an increase in the consolidation of North Logan Square in District 35, as its border had formerly been Kedzie to the Illinois Centennial Monument before going South along Sawyer to Fullerton, North Spaulding to Palmer, and then North St Louis to Dickens. In contrast, the 1st District was moved north and west, gaining far more of North Logan Square than the small pieces it had from the 2015 map, while District 32 was moved east, losing North Logan Square entirely. The 25th Precinct of the Chicago Police Department includes North Logan Square west of Central Park Avenue, while the 14th Precinct occupies the rest, including Tract 2106.02.

History

North Logan Square's history is that of the Logan Square community area. Logan Square was named after General John Logan, a Union Civil War veteran who later served as a Republican senator from Illinois. The area became heavily built up and dense early-on as a northwestern gateway neighborhood for immigrants. The population through the early-20th century consisted mainly of Scandinavians and Germans before they were joined by Norwegians, Russian Jews, Italians, and Poles (a group that comprised 37.8% of the Logan Square Community Area population by 1950, per the 1958 City of Chicago Study of the Logan Square Community Area (City of Chicago 1958, 6)). By 1930, the community area hit 114,174 – its high point, declining to 106,763 in 1950 (City of Chicago 1958, 3), to 71,665 by 2020, according to the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP). The neighborhood became heavily Hispanic throughout the late 20th century, with Chicago Studies describing it as populated by Mexican, Cuban, Puerto Rican, and Central American immigrants. The community area became majority white in the 2010s, however, going from 65.1% Hispanic or Latino in 2000, compared to 51.6% White in 2020, per CMAP. This, along with a jump in the median income from $57,888 to $84,653 and a drop in the population by 13.4% from 2000 to 2020 are symbols of gentrification taking place in the community area, an ongoing phenomenon informing current fights about affordable housing.

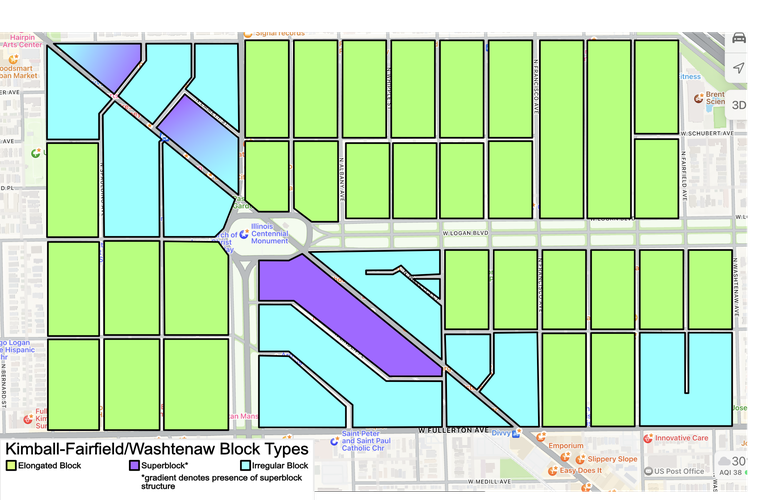

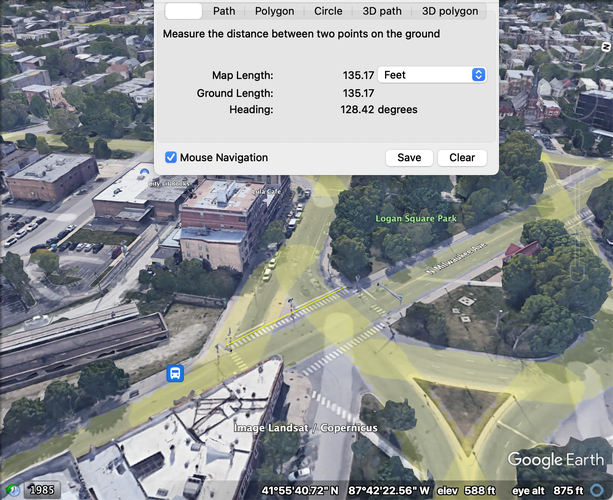

The history of North Logan Square is a history defined by Chicago central city planning as well as the decentralized actions of individual developers and community organizations. Although the area covered by the community area began as a “prairie farming village,” per Chicago Studies, the area quickly became part of Chicago’s urban area (read: not yet formally part of the city) in the mid-19th century following the construction of Milwaukee Avenue. The area was officially annexed in 1889, by which point the area had become densely populated following the 1871 Great Chicago Fire, something Chicago Studies attributes to its location outside the burn zone. The construction of Milwaukee Avenue and its predecessors, the North and Western Railroad (both of which preceded the post-fire population growth) and then the Northwest branch of the “L” all served as examples of central planning structuring the growth of the neighborhood. The neighborhood was further altered by the late 19th century construction of the Chicago Boulevard system, which reaches its northernmost point at the center of North Logan Square – the square itself, where the 1911 Illinois Centennial Monument stands – and goes East along Logan Boulevard.

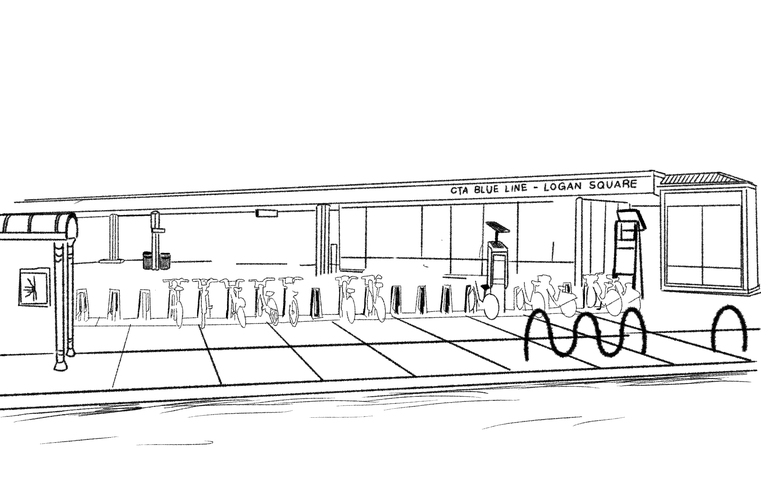

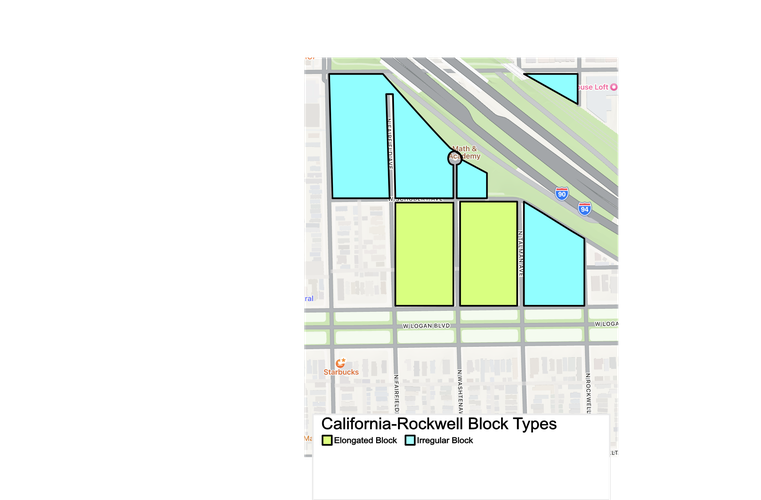

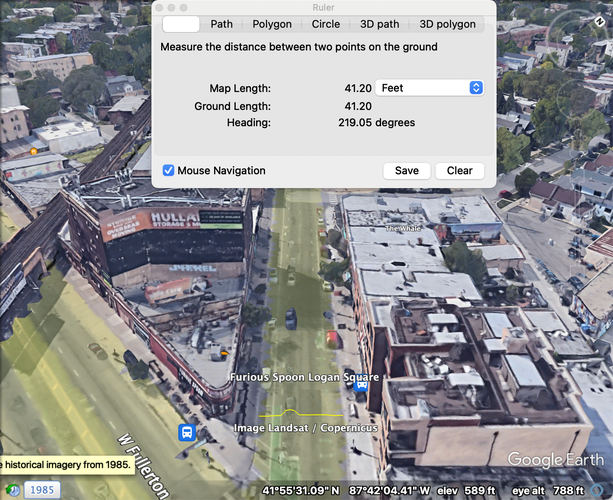

Chicago Studies also blames the construction of the Blue Line (chiefly the construction of the underground Logan Square station) and the construction of I-90 for harming the neighborhood as a form of urban renewal. Notably, the 1958 Chicago Community Survey described the area as “completely built up” (City of Chicago 1958, 4) where things could only be constructed following the destruction of existing buildings. Such a statement was unfortunately made true by the construction of the Eisenhower Expressway portion of I-90 in particular, the impact of which is clear through a WBEZ article called “Displaced.”

The Community Survey assessment remains true today; even with a reduced population, Logan Square is highly dense when compared to Hyde Park and Woodlawn. While I-90 still makes a near-formal barrier on the northeast corner of the neighborhood, the Blue Line now serves as the main anchor of North Logan Square to the Loop, much as the Milwaukee branch of the Metropolitan West Side Elevated (one of the pre-CTA transit networks) did. Although the general structure of North Logan Square remains the same, structured along Milwaukee and the L with the boulevards as well as Fullerton and Diversey serving as seams, the neighborhood composition has changed through gentrification, a largely decentralized challenge that city/ward-level policy is only beginning to respond to.

“CMAP Community Data Snapshot | Logan Square - Illinois.” Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, July 2022. https://www.cmap.illinois.gov/documents/10180/126764/Logan+Square.pdf.

Birnbaum, Mike. “Blue Line Station: Doors Open on the Left at Logan Square.” LoganSquarist. January 28, 2013. https://logansquarist.com/2013/01/28/history-blue-line-station/.

Loerzel, Robert. “Displaced | When the Eisenhower Expressway Moved in, Who Was Forced Out?” WBEZ 91.5 Chicago. Accessed October 17, 2022. https://interactive.wbez.org/curiouscity/eisenhower/.

“The History of Logan Square.” Chicago Studies | The University of Chicago. The University of Chicago. Accessed October 17, 2022. https://chicagostudies.uchicago.edu/logan-square/logan-square-history-logan-square.

Morris, John. “A Brief History of Milwaukee Avenue, Part 1: an Indian Trail Becomes Dinner Pail Avenue.” Web log. Chicago Patterns (blog). Chicago Patterns, July 4, 2016. http://chicagopatterns.com/a-brief-history-of-milwaukee-avenue-part-1-an-indian-trail-becomes-dinner-pail-avenue/.

Long, Zach. “Logan Square, Chicago Neighborhood Guide.” Time Out Chicago. Time Out Group Plc, November 12, 2021. https://www.timeout.com/chicago/things-to-do/logan-square-guide-the-best-of-the-neighborhood#:~:text=The%20neighborhood%20takes%20its%20name,large%20homes%20along%20the%20boulevards.

City of Chicago Commission on Human Relations Research Department, “Study of the Logan Square Community Area, February 1958.

Bloom, Mina. “Nearly 700 People Apply For 50 Apartments In New Logan Square Complex, Showing ‘Dire Need’ For Affordable Housing In Area.” Block Club Chicago. July 22, 2021. https://blockclubchicago.org/2021/07/22/logan-square-affordable-housing-700-apply-50-apartments-emmett-street-complex/.

Chicago ''l''.org: Stations - logan square. Chicago ''l''.org. Accessed December 4, 2022. https://www.chicago l.org/stations/logan_sq.html.

Identity

When I visited North Logan Square, practically no one was outside the morning of Thursday, October 13th. As I walked around on that chilly day, the only group of people I saw out was at Chiqueºlatte, a Netherlands (and Luxembourg)-based coffee shop whose only non-European location is in Logan Square. I also did not see any gates or signs or bike racks akin to the Hyde Park racks that would serve as an official delineation of community identity. In this context, the main aspect of built form that I see as helping create a sense of neighborhood identity is North Logan Square’s street art.

There is a ton of street art surrounding Milwaukee Avenue in North Logan Square. Exiting onto the Paseo Prairie Community Garden-adjacent exit of the Logan Square station brings you out next to an elaborate Pokemon mural. Later, I came across an alley just north of Diversey of the Beatles. The most visible marker of Logan Square identity came on the side of a coffee shop called The Brewed coffee, in the form of two murals: A dark-skinned Rosie the Riveter flexing her bicep in her signature “we can do it” pose next to a unique, mirrored rendition of the Chicago skyline. Surrounding the upward and downard buildings were different fonts spelling out the names of Chicago’s neighborhoods, with Logan Square done in an elegant cursive font. In between the skylines were a green leaf, a Chicago star colored in with rainbow colors, a crossed-out gun, and a red Black power fist.

Ironically, this mural (painted by @menaceresa) is north of Diversey, just like the LSNA/Palenque headquarters. However, it encapsulates a particular presentation of Logan Square identity as built on solidarity and support for one another against all forms of harm, whether it be discrimination and neglect or gentrification and displacement. It is worth noting that all of these themes are present on the LSNA/Palenque website. The website describes their identity as a community group as being forged in the 1970s and 1980s when the neighborhood became primarily Hispanic and also low-income, as it worked to serve these new residents.

The Brewed mural is thus a uniquely political mural among those that I saw, but all of them act as a form of placemaking that can be interpreted as a sign of community ownership and organization much in the way that gates and signs are interpreted. This theory is especially supported by articles such as the Chicago Sun-Times Logan Square Street Art Guide, which identifies Logan Square as a neighborhood defined by its street art.

With regards to identity, one final note from my initial neighborhood reconnaissance was my observation of an apartment building sporting block letters in its L-facing window reading “livelogan.com.” It was the only major marker of Logan Square that resembled any form of neighborhood branding (particularly when compared to street art that can be interpreted as more organically defining the neighborhood to its inhabitants). This relationship between corporate, gentrifying interests and existing residents and how it impacts Logan Square’s identity for residents and outsiders is something I plan to explore further in later assignments.

Ali, Tanveer. “Logan Square Street Art Guide from The Grid.” Chicago Sun-Times Guides. Accessed October 17, 2022. https://guides.suntimes.com/street-art/logan-square/.

“What We Do.” Palenque LSNA. Palenque LSNA. Accessed October 17, 2022. https://www.palenquelsna.org/about.

Videos of Street Art

1. https://youtu.be/OB_9QoPf5lY

2. https://youtu.be/8r09I4rQhHA

3. https://youtu.be/I16vVSaCK80

Social Mix

Demographic Analysis

Looking at demographics for North Logan Square (with and without Tract 2106.02, the Avondale/Logan Square border tract) as well as the Logan Square Community Area, the Northwest Side, and Chicago at large, my main takeaway is that none of these areas are racially/ethnically diverse. I recorded eight categories for race/ethnicity: White Alone, Black or African American Alone, American Indian or Alaska Native Alone, Asian Alone, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander Alone, Some Other Race Alone, Two or More Races Alone, and Hispanic or Latino. Only one location scored above ⅜; the City of Chicago, which scored 3.56/8. North Logan Square (sans Tract 2106.02) scored 2.39/8, while North Logan Square with Tract 2106.02 scored 2.44/8. The Logan Square Community Area (as approximated by census tracts) scored 2.47/8, the Northwest Side (similarly approximated by census tracts) scored 2.55/8. In short, no area I observed is incredibly diverse, but North Logan Square in particular is not diverse when it comes to race / ethnicity both from an objective sense (looking at its Simpson Diversity Index score), but also when compared to Chicago at different spatial levels.

This lack of racial/ethnic diversity contrasts with the high level of diversity I observed at all levels for income. It also contrasts with the relatively high level of diversity I observed at all levels for education for residents. With 16 household income divisions (with incomes adjusted for 2020 inflation) and eight education divisions (for residents 25+ years old), Chicago at large scored 13.49/16 and 5.17/8, respectively. North Logan Square sans Tract 2106.02 scored 12.08/16 and 4.21/8, while North Logan Square with Tract 2106.02 scored 12.01/16 and 4.34/8. Similarly, the Logan Square Community Area scored 11.58/16 and 4.52/8, and the Northwest Side scored 12.71/16 and 4.92/8. Interestingly, the entire community area had the least income diversity, while both North Logan Square configurations had the lowest levels of educational diversity, although the difference compared to the other scales of analysis is not especially pronounced. Similarly interesting is North Logan Square and Logan Square Community Area’s lack of age diversity when compared to the Northwest Side and the city at large. With 12 age divisions, North Logan Square sans Tract 2106.02 scored 5.94/12, North Logan Square with Tract 2106.02 scored 6.21/12, and Logan Square Community Area scored 5.7/12, while the Northwest Side and the City of Chicago scored 8.91/12 and 8.77/12, respectively. Even so, the fact that both versions of North Logan Square score above eight for income and (barely) above four for education leads me to declare the neighborhood income and (somewhat) educationally diverse, even as it is decidedly not diverse racially/ethnically or age-wise, phenomena I intend to research further if this project allows me to.