Overview

Cabrini-Green: A neighborhood in flux

Size

While it's difficult to approximate the exact population of the neighborhood, as its boundaries do not align perfectly with Census tracts, based on an approximation of Census tracts and block groups, Cabrini-Green is home to roughly 8,000 people. While this is somewhat larger than the ideal neighborhood of 5,000 as proposed by early planners like Clarence Perry, the geographic extent of the neighborhood is relatively small and contained.

Identity

Today, there are few visible signs demarcating the neighborhood from its surroundings. On my walk through the neighborhood, I saw no signage referencing "Cabrini-Green." Instead, realty agencies advertised the neighborhood's proximity to downtown, schools and community centers referenced the city of Chicago rather than any particular neighborhood, and the "for lease" signs hanging on new developments identified the neighborhood only as part of the larger geographical area of the Near North Side. In contrast, Old Town, just a few minutes away by foot, was easily identifiable by the large iron-grated signs reading "Old Town" on the neighborhood's most trafficked streets.

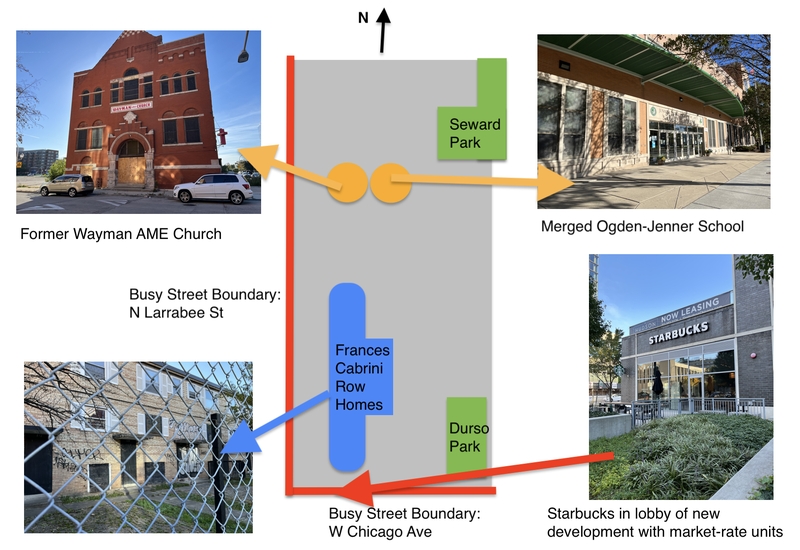

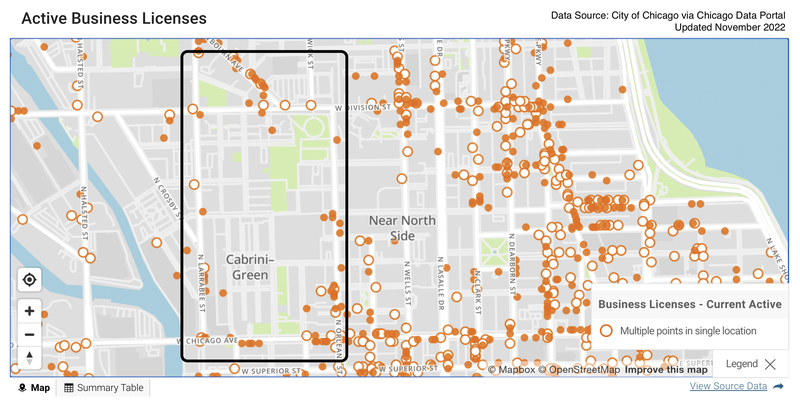

When I visited the neighborhood on a sunny Saturday afternoon, there were few cars on the street or pedestrians on the sidewalk. While I spotted some young adults walking their dogs near the gated townhomes closer to the north side of the neighborhood, the sites of the former Cabrini-Green high-rise towers were almost completely empty. On both W Chicago Ave, which bounds the neighborhood from the south, and N Larrabee St, which bounds it from the west, I was the only pedestrian. The lack of people on the street may be due to the fact that the majority of the neighborhood is residential space, and that a primary factor attracting residents to the neighborhood in the first place is that is makes for an easy commute to already-existing jobs downtown.

[Above: New townhomes near the former William Green high-rise towers]

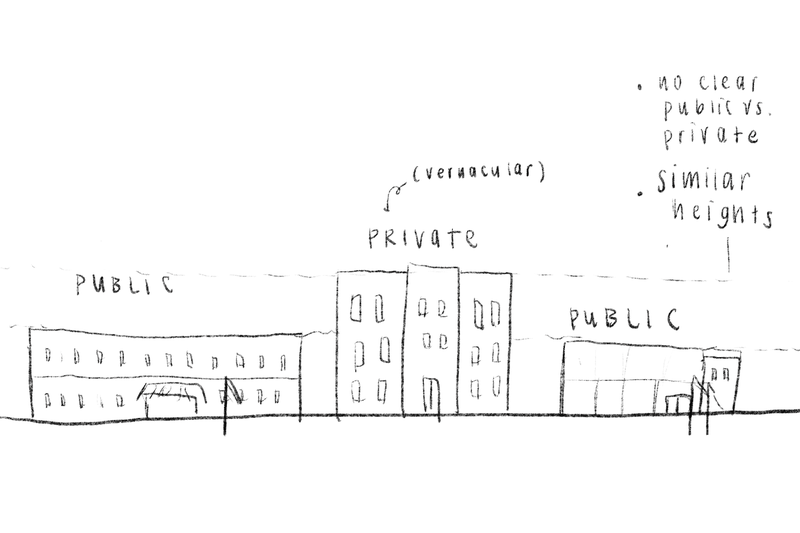

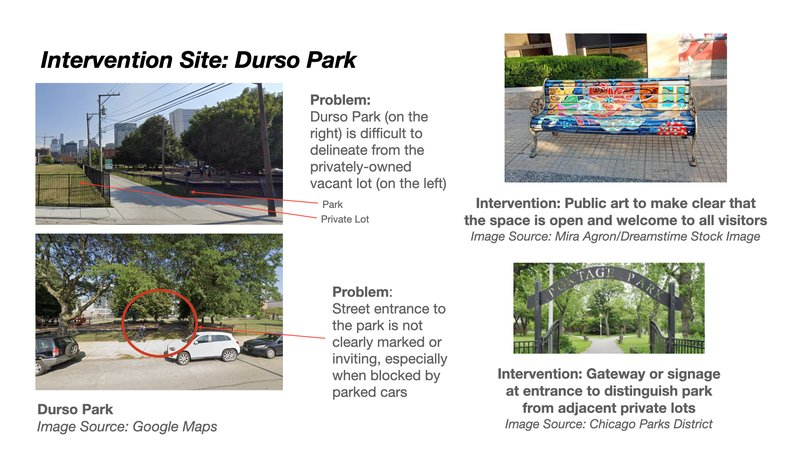

Cabrini-Green is home to a large number of open green spaces and parks, but few of these public green spaces provide any shared facilities for residents, whether that be benches, a well-groomed sidewalk or trail, or public bathrooms and trash cans. This too contributed to the sense that this was a neighborhood without a clearly-defined center or identity. Even the streets near neighborhood institutions like the Jenner-Ogden elementary school that often serve as neighborhood centers were little-trafficked; the school sat directly across from the now-closed Wayman AME Church that once served a large congregation of predominantly Black residents of the public housing project—likely acting as a point of neighborhood identity and cohesion—but now serving to shed light on the lack of central gathering places or strong identifying places.

Layers

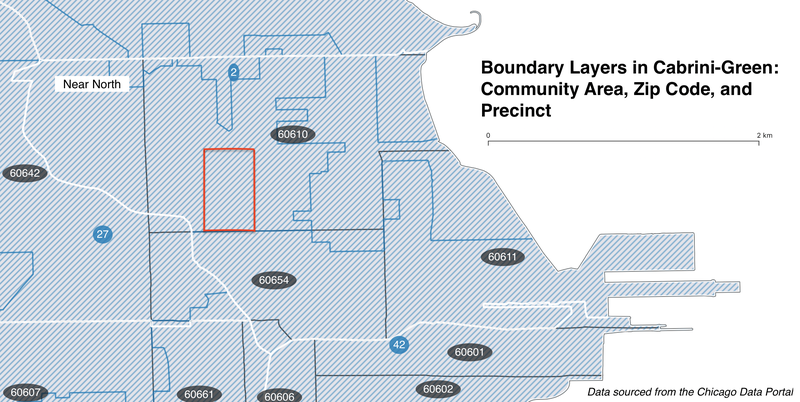

This map depicts the current boundaries of the community areas (in white), zip codes (in black), and ward precincts (in blue) to which Cabrini-Green belongs. The neighborhood boundaries here are roughly outlined in red. As shown above, the entirety of Cabrini-Green, as a relatively geographically contained neighborhood, belongs to the same community area, zip code, and precinct.

Diagram

History

Named after the public housing projects that were home to upwards of 15,000 residents at their peak, Cabrini-Green today is a neighborhood in flux, with the boarded-up Frances Cabrini Rowhouses sitting across the street from new market-rate condos from private developers.

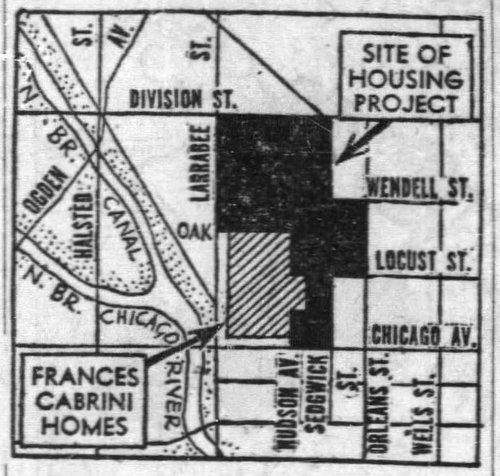

Before the neighborhood was known as Cabrini-Green, it was known as "Little Hell," due to the nearby oil refinery on Hobbie St and the slumlike conditions in which the majority European immigrant population lived. In a 1929 book, sociologist Harvey Zorbaugh dubbed the Lower North community to which the neighborhood belonged "The Gold Coast and the Slum," observing the mansions and wealth directly to the east of where of Little Hell. Today, Hobbie St is home to both the neighborhood's newly merged Ogden International-Jenner School, the empty lots where public housing units once stood, and the Basecamp River North development of new mixed-income townhomes. The transformation of the neighborhood from the early 20th century to what it looks like in the 2022 is tied to the extensive Cabrini-Green public housing projects that gave this neighborhood its identity in the mid-to-late 20th century.

In the 1940s, the city of Chicago demolished the shanties and dilapidated homes of Little Hell and began constructions on the first part of this extensive Chicago Housing Authority project, starting with the Frances Cabrini Homes. Today, these rowhomes are the only remaining structures from the Cabrini-Green public housing, although the majority are boarded-up and empty; the last of the high-rise towers that became popular media symbols of the failures of public housing was fully demolished in 2011. But today, rather than the city of Chicago stepping in to to redevelop the area, the neighborhood has become a desirable commercial location for private developers to build new market-rate units.

[Above: The Frances Cabrini Homes today, fenced off and boarded-up]

The original Cabrini-Green Homes were home to a racially heterogeneous mix of residents, primarily housing war veterans (due to repurposing for World War II), some of Little Hell's original Italian and Irish population, and increasingly Black Americans, who moved in as they continued to be excluded from affordable, quality housing in Chicago's racially segregated neighborhoods. Early residents were also carefully screened to meet the CHA's criteria for "low-income" but now "extremely low-income," as the city embarked on an urban renewal project with the hopes of remaking Little Hell into a safer neighborhood and a convincing argument for the power of public housing.

In the 1960s, CHA built the William Green Homes on Division St, adding 1,000 units and introducing a new type of housing—high-rise buildings instead of the previous two-story rowhomes. Arguably in part because of the way the high-rise buildings isolated residents from their surroundings and allowed for the extreme spatial concentration of poverty, but also because of factors like neglect and poor maintenance by the city and under-funding and de-prioritization of the CHA, by the 1970s, Cabrini-Green was no longer a "model" of public housing, but an oft-derided example of its failures. The predominantly Black residents of Cabrini-Green experienced a rise in crime, poverty, and further disinvestment in the neighborhood. By 19956, the City had announced a new plan for affordable and public housing in Chicago and planned for the demolishment of the majority of Cabrini-Green.

Since demolition began at the turn of the century, former residents of the Cabrini-Green homes have been protesting how they have been priced out of the new Cabrini Green neighborhood. While new mixed-income development was supposed to provide replacement housing for public housing residents, displaced residents were mostly been scattered across the city of Chicago due to the slow pace and low quantity of construction, with fewer than 400 replacement public housing units built as of 2012, more than a decade after residents were first displaced. In 2015, following years of federal litigation, Chicago agreed to convert at least 176 units of the Frances Cabrini rowhomes to public housing and add additional incentives for developers to build low-income units.

Sources

Bittle, Jake. “What Is the CHA Doing?” South Side Weekly, April 16, 2019. https://southsideweekly.com/cha-plan-for-transformation-haunts-chicago/.

Chicago Reader. “‘A City within a City.’” Chicago Reader, March 30, 2021. http://chicagoreader.com/news-politics/a-city-within-a-city/.

Chicago Tribune. “Cabrini-Green Timeline: From ‘War Workers’ to ‘Good Times,’ Jane Byrne and Demolition.” Accessed October 5, 2022. https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/ct-cabrini-green-timeline-20201220-zti7msps6zerxpye72h6qxbfxy-story.html.

Magnusen, Emily. “The Fight to Stay at Cabrini-Green Chicago Public Housing Special.” Public Interest Law Reporter 16, no. 2 (2011 2010): 176–82.

Ruiz-Tagle, Javier. “The Broken Promises of Social Mix: The Case of the Cabrini Green/Near North Area in Chicago.” Urban Geography 37, no. 3 (April 2, 2016): 352–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2015.1060697.

Vale, Lawrence. “Housing Chicago: Cabrini-Green to Parkside of Old Town.” Places Journal, February 20, 2012. https://doi.org/10.22269/120220.

Also referenced: GIS data from the Chicago Data Portal and Census.gov.

Social Mix

Basic Demographics

To summarize the basic demographic data available for Cabrini-Green, I used ACS 2020 5-Year estimates for three Census block groups: Tract 804, Block Group 1; Tract 819, Block Group 1; and Tract 8383, Block Group 1. While these block groups do not correspond exactly to Cabrini-Green's boundaries — for example, the southeast corner of the neighborhood belongs to a different block group which I excluded because the majority of the block group is outside the neighborhood boundaries — they should be accurate enough to provide a broad overview of the neighborhood's overall demographics.

The tables communicate aggregated data for all three block groups in the neighborhood. I wanted to note a few key demographic differences between these block groups. First, the southern portions of the neighborhood closer to downtown are much whiter than the northern portions of the neighborhood. The Block Groups in Tract 819 and 8383 are majority white, while Block Group 1 in Tract 804 in the northernmost portion of the neighborhood is majority Black. Second, while median house value for owner-occupied units did not vary greatly across the three block groups, median gross rents varied significantly. In Tract 819, Block Group 1, which covers the western portion of the neighborhood and includes the former sites of the Cabrini-Green public housing project, median rent is $2,472—more than double the median rent for the aggregated neighborhood. Finally, Tract 819, Block Group 1 was also the only block group where owners occupied the majority of units; in the other two block groups, the proportion of renters was much higher than of owners.

Diversity

To calculate my Simpson Diversity Indices, I used the same race, age, and educational attainment variables that I used to compile the basic demographic tables above, again using ACS 2020 5-Year estimates. The community area (Near North Side) and the region (Near North Side) to which Cabrini-Green belong share the same boundaries, so the category of "Near North" in the table includes data that applies to both designations. Since the Census Bureau does not collect data on the community area level, I calculated the indices by summing data from each of the tracts included in the community area: tracts 801, 802.01, 802.02, 803, 804, 810, 811, 812.01, 812.02, 813, 814.01, 814.02, 814.03, 815, 816, 817, 818, 819, and 8422.

Analysis

Based on the Simpson Diversity Indices for the Cabrini-Green neighborhood, the Near North Side community area/region, and the City of Chicago, Cabrini-Green is significantly more diverse than the Near North Side but slightly less diverse than the city as a whole. In particular, residents of the Near North Side are more likely to be white and to have a higher level of educational attainment than residents of Cabrini-Green or Chicago. In other words, Cabrini-Green is distinguished from its immediate community area by virtue of its racial and educational diversity, as it is home to more non-white residents (particularly Black residents) and more residents with a high school diploma or less. Given that Chicago, like many big American cities, is known for having a history of racial and economic segregation, it makes sense that individual community areas and regions like the Near North Side are less diverse than the city as a whole. Cabrini-Green's relatively recent history as the home to a large public housing development likely contributes to its relative diversity in the context of the Near North Side. However, while I would argue that Cabrini-Green today is a diverse neighborhood, it's unclear whether the neighborhood will be able to retain its economic or racial diversity or if the neighborhood will, like the nearby River North or Gold Coast neighborhoods, become less affordable or accessible to residents of different socio-economic classes.