Overview

-- Introduction, Size, and Boundaries --

:: History ::

Since its founding in 1886, Edgewater has been defined by its glamorous condominiums which sit on Sheridan Road, right on the coast of beautiful Lake Michigan. Though the neighborhood sits nearly eight miles from the center of Chicago, it is lined with a row of tall condos, each ten to twenty stories in height with sprawling balconies and beautiful lake views. Within a city defined by its industrial nature and cold, harsh weather, Edgewater’s condos construct an oasis from the inhuman city. However, just like the neighborhood, these condos haven’t always been what they seem and despite their luxurious appearances, there is a complex history behind how these condos came to be what they are today.

Edgewater’s modern history began when developer John Lewis Cochran purchased a large swath of land north of the Lakeview community in 1886. The neighborhood originally consisted of a collection of mansions along the lakefront built for wealthy families in Chicago looking for places to stay during the warm summer months. These mansions were the precursor to the construction of the luxurious condos which now sit on the lakefront. The Edgewater neighborhood had many luxurious features such as sidewalks, streetlights, and sewers installed on the streets even before the arrival of residents, however, the one thing it lacked was direct access into the city via rail, which would truly solidify Edgewater as a neighborhood. In order to mitigate for this, Cochran convinced the Chicago, Milwaukee, and St. Paul Railroad to extend their service to Bryn Mawr Avenue, a central thoroughfare of Edgewater.

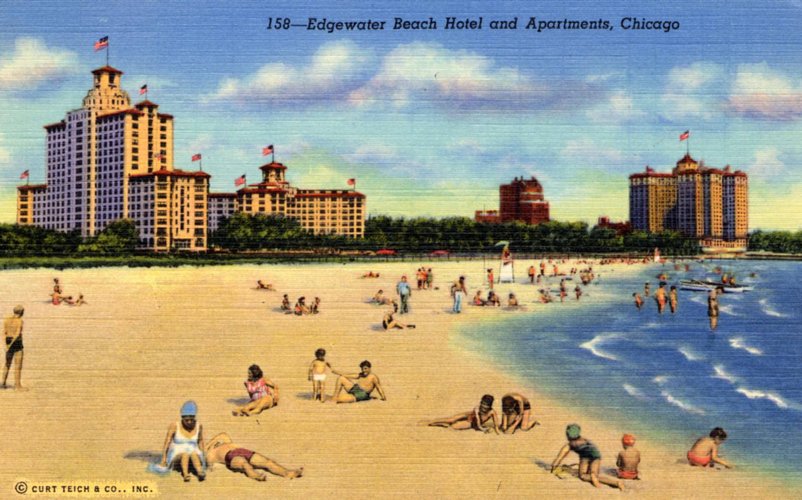

With the extension of railroads to Edgewater, a plethora of Chicago residents fled into Edgewater prompting the development of the high-density condo buildings seen today along Sheridan Road. The Edgewater Beach Hotel and the Edgewater Beach Apartments were built during this time in a sunrise yellow and sunrise pink color. These two buildings came to define the Edgewater neighborhood and its excessive wealth and glamour. This was assisted by a “Highest and Best Use” zoning ordinance which made high-density apartments part of the building code and prompted the construction of apartment buildings all along the coast. Buildings like these began popping up along the lakefront throughout the early 1920s, and Edgewater began to solidify itself as one of the most luxurious areas in Chicago. As housing prices rose along the lakefront, multi-family apartment buildings and single-family homes started filling in the western areas of the neighborhood. During this time the historic Lakewood-Balmoral district was constructed, along with many of the historic single-family homes in Edgewater Glen.

With the onset of World War II and the continued struggles of the Great Depression, Chicago entered a city-wide housing crisis, and the large mansions and condos which defined the neighborhood were forced to be broken up into small units in order to make room for more residents. This attracted many new ethnic groups to Edgewater and neighboring Uptown. The increase in the density of residents led these once glamorous condos into disrepair, and residents began to grapple with overpopulation and pollution in their living quarters. This decline in glamour and unique character led sociologists at the University of Chicago to declare that Edgewater was in fact not its own community, but a part of Uptown. As soon as the glamour along the lakefront began to deteriorate, the character of Edgewater also achieved a low point.

As the housing shortage eased in the early 1950s, and the country began to work its way out of the Great Depression, developers in Edgewater began constructing multi-unit condos along the lakefront in the locations of old family mansions, however as residents began moving out of the city for the suburbs, Edgewater began to see high levels of vacant residences. At this point, Edgewater was in desperate need of organization, and a strategy to save the neighborhood from vanishing. Because of this, the Edgewater Community Council was formed. This group strove to deal with the problems created by the deteriorating housing that had made the strip of roads adjacent to the lake unsafe and unattractive. This included the demolition of the sunset-yellow Edgewater Beach Hotel which had defined the character of Edgewater only fifty years prior. With the demolition of this building, a new era of Edgewater was born. Immigrant groups continued to flood into the Edgewater area as conditions began to improve. Libraries, museums, and community centers were constructed in the new Edgewater community, and the neighborhood seemed to be on a trajectory to become a great neighborhood once again. In response to this, Edgewater was finally recognized as its own community area by the city of Chicago in 1980.

Today, Edgewater is still a neighborhood defined by its residential buildings with its high-rise condos along the coast, apartment buildings around Broadway, and single-family homes in the western reaches of the neighborhood. The sunset-pink Edgewater Beach apartment building stands as a reminder of the neighborhood's glamourous past as it towers next to other high-rise condos which nowadays house a diverse group of residents. Much like the Edgewater Beach Apartments, Edgewater had to be shifted, repurposed, and rebuilt in order to reach its current status as one of Chicago’s great neighborhoods.

Sources:

Maly, Michael T., and Michael Leachman. “Chapter 7: Rogers Park, Edgewater, Uptown, and Chicago Lawn, Chicago.” Cityscape 4, no. 2 (1998): 131–60. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41486480.

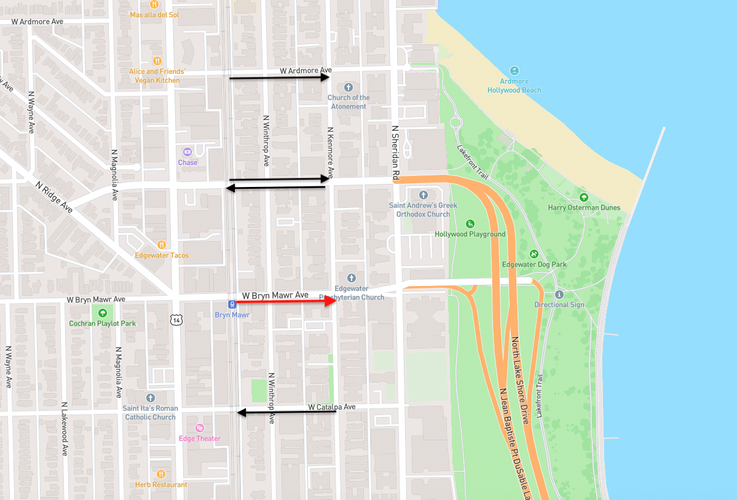

Marciniak, Ed. Reversing Urban Decline: The Winthrop-Kenmore Corridor in the Edgewater and Uptown Communities of Chicago. 1981.

Seilgman, Amanda. “Edgewater.” Encyclopedia of Chicago. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/413.html

Wikipedia contributors, "Edgewater, Chicago," Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Edgewater,_Chicago&oldid=1116565554

:: Size ::

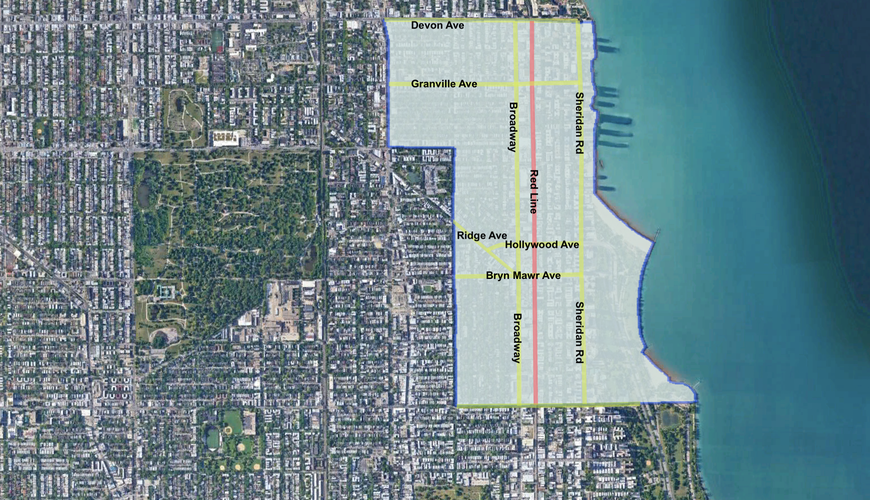

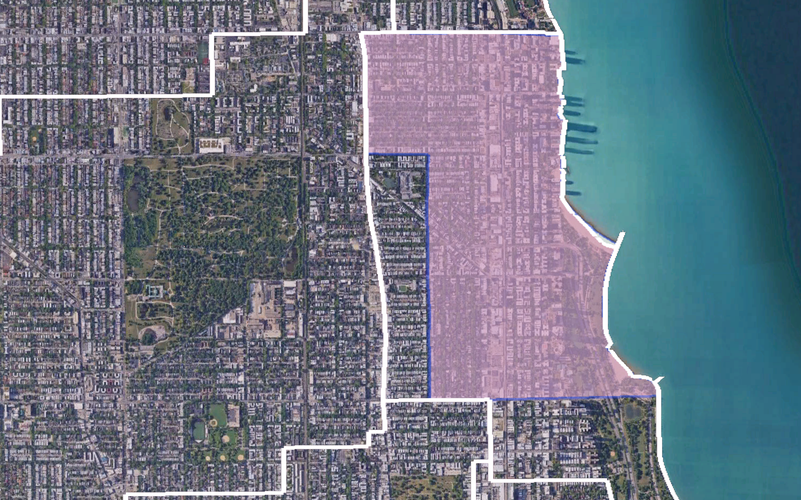

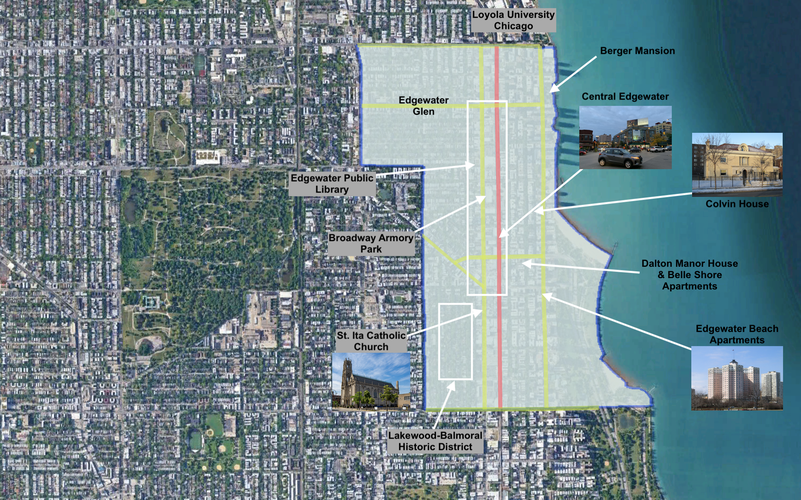

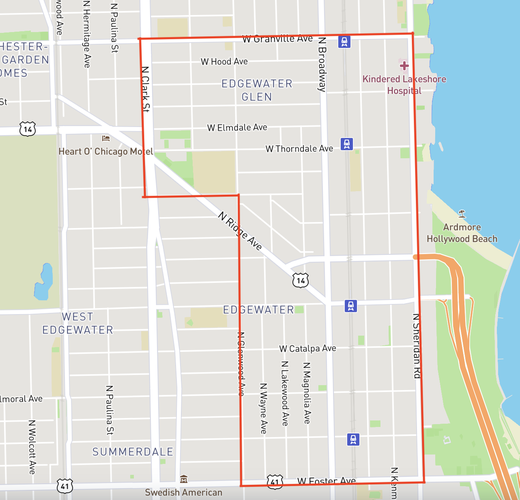

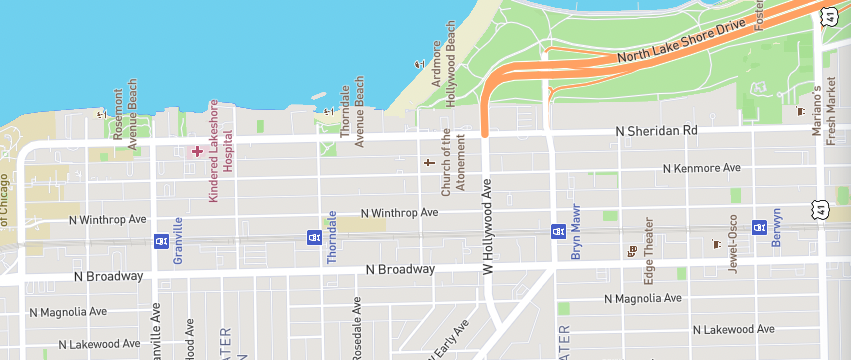

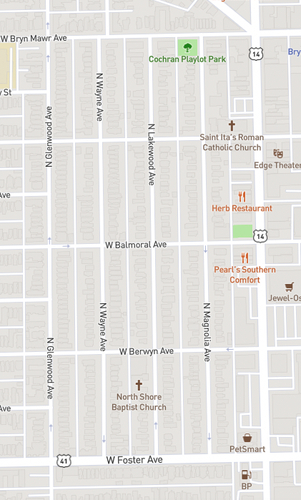

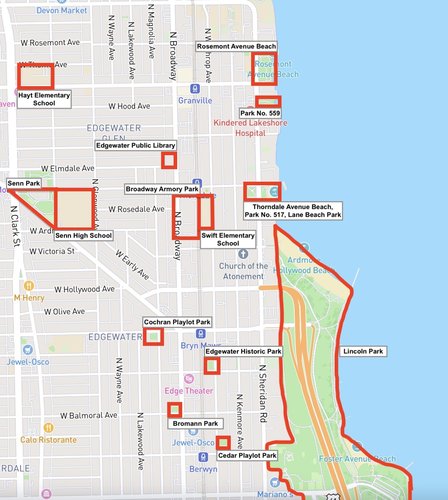

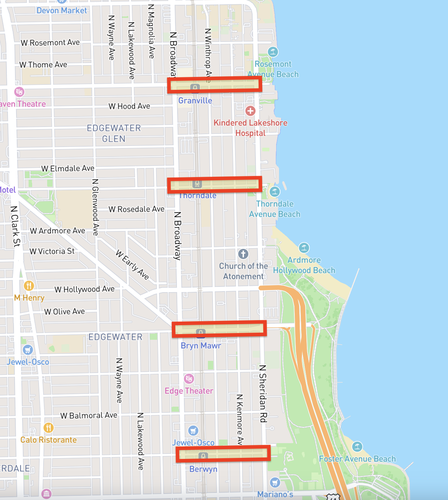

Edgewater is a large neighborhood, both in the sense of geography and

population. The following map is a representation of the neighborhood

boundaries of Edgewater which I determined best defined the extent of the

neighborhood. The map is also labeled with major thoroughfares and

transit lines that run through the neighborhood. Using Google Earth, the

area of Edgewater is determined to be 716 acres or 1.12 square miles.

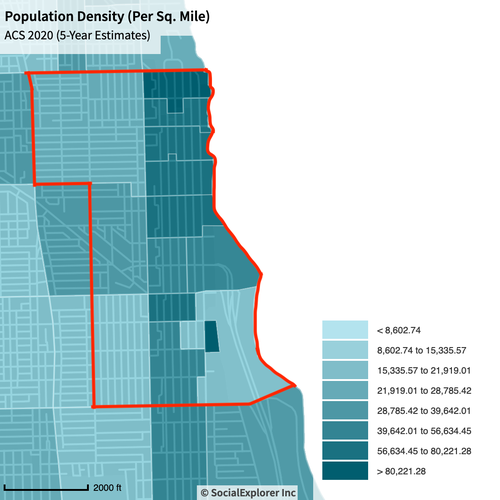

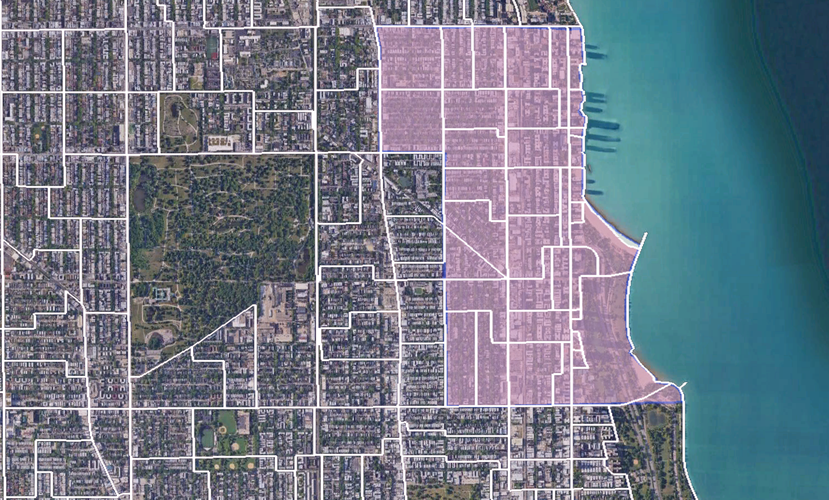

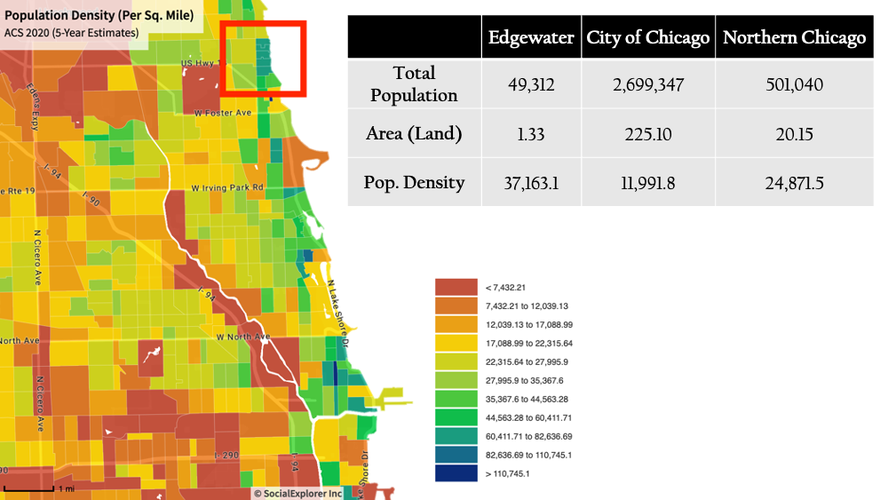

Using socialexplorer.org the population of Edgewater within the above boundaries was determined to be within a range of 40,000 to 45,000 people. The uncertainty of this value is a result of neighborhood boundaries cutting through census blocks, requiring estimation of the population within certain census areas. The following map shows the distribution of population in census blocks around the Edgewater neighborhood with the neighborhood boundaries drawn on top.

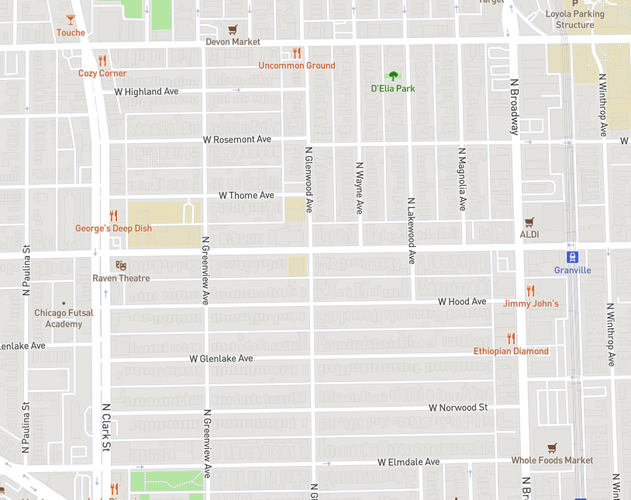

:: Layers ::

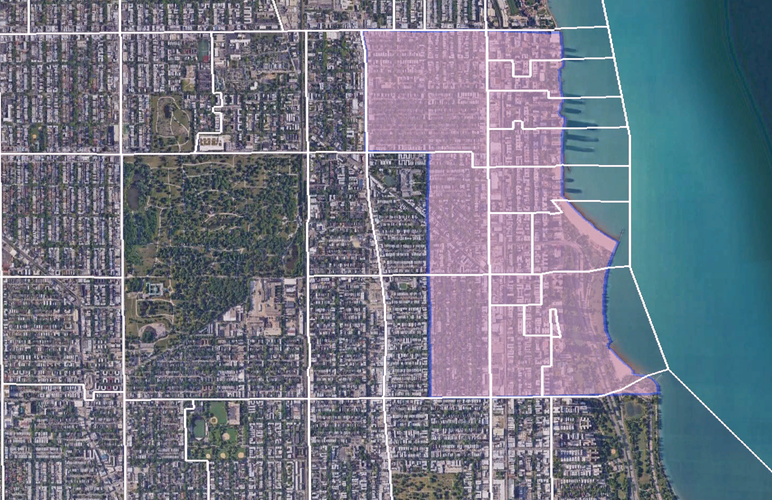

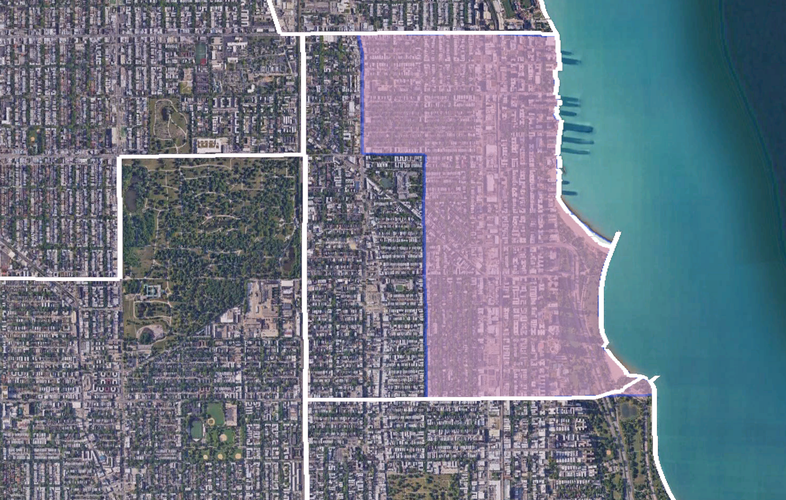

The following maps show various borders overlayed on a map of Edgewater

using Google Earth. The spatial data is provided by the Chicago open

data portal.

Census Tracts overlayed on Neighborhood Boundaries:

Community Area map overlayed on Neighborhood Boundaries:

Ward Map overlayed on Neighborhood Boundaries:

Precinct Map overlayed on Neighborhood Boundaries:

-- Neighborhood Identity --

Upon arriving in Edgewater via the red line, a neighborhood identity is quite apparent. The central stop of the Red Line in Edgewater is Bryn Mawr station which stops on the avenue of the same name. Along Bryn Mawr Avenue are custom bike racks with the neighborhood logo, and several businesses with the “Edgewater” in their title. Further west on Broadway, this identity is also apparent with street guides of the neighborhood and signs hanging on light posts with the Edgewater logo. Bryn Mawr and Broadway are two of the main thoroughfares through Edgewater, and both streets house plenty of paraphernalia to suggest a certain level of neighborhood identity. While walking along these streets, visitors and residents are fully aware of what neighborhood they are in. Another element of Edgewater’s identity which helps boost this identity is the strong boundaries the neighborhood has with its surrounding communities. There is a clear distinction between Edgewater and the neighborhood to its south, Uptown, as well as the neighborhood to the southwest, Andersonville. Immediately upon crossing Foster Avenue to the south, street signs begin to read “Uptown,” and the paraphernalia which defined Edgewater disappear. The same goes for Clark Avenue on the southwest side, as the neighborhood abruptly shifts into “Andersonville” upon arriving on Clark, and for Devon Avenue on the North with abrupt shifts to Loyola University’s community area upon crossing over Devon.

Overall, along the main thoroughfares, the identity of Edgewater is very strong. However, this identity is limited, almost completely, to the main thoroughfares such as Bryn Mawr, Broadway, and Devon. Outside of these areas, there is very little infrastructure that suggests a neighborhood identity. There are no signs on lamp posts, very few businesses with Edgewater in the name, and no streets with names concerning their existence within or without the Edgewater community. This is especially pertinent in the northwest area of Edgewater, where there is no sense of a neighborhood border. The northwest corner does not border any large neighborhood area, so unlike when crossing out of the neighborhood from the south, southwest, or north, there is no real sense for when Edgewater begins and ends.

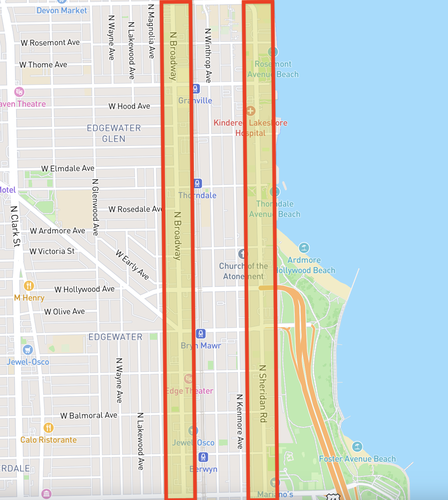

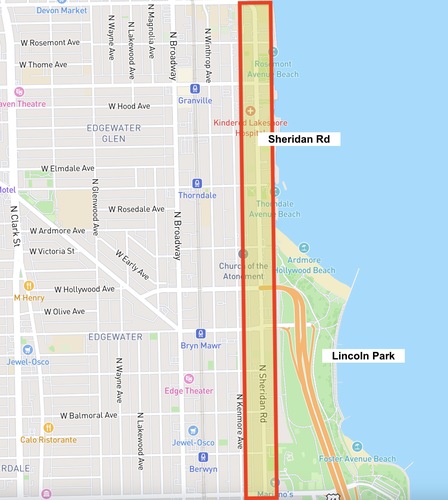

Interestingly, along Sheridan Avenue towards the central and southern portions of the neighborhood, a separate identity seems to override the neighborhood identity shown on streets such as Bryn Mawr, Broadway, and Devon. Many of the high-rise apartment buildings here are named in relation to their proximity to the beach, and a certain identity is built amongst these dwellings separate from the identity of Edgewater. While there are a few Edgewater signs scattered along Sheridan Road, the main characteristic which much of this street shares are property names like “Beach Side Apartments,” “Beach Point Tower,” “Edgewater Beach Apartments,” “Sheridan Lakeside Condos,” and “Shoreline Tower Condos.” This messaging, combined with reduced messaging surrounding the Edgewater neighborhood as a whole create a sub-community within Edgewater’s boundaries creating confusion regarding this area’s involvement in the greater Edgewater neighborhood.

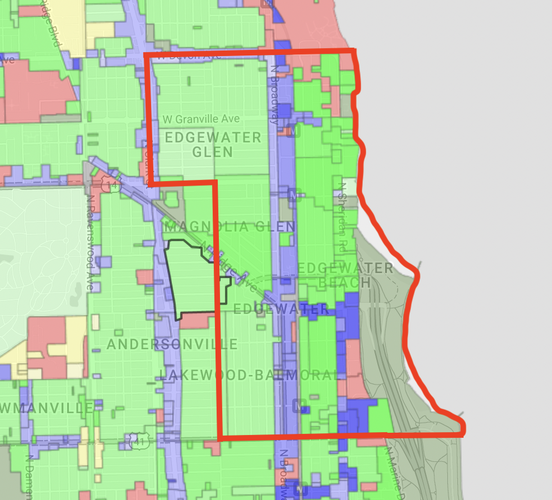

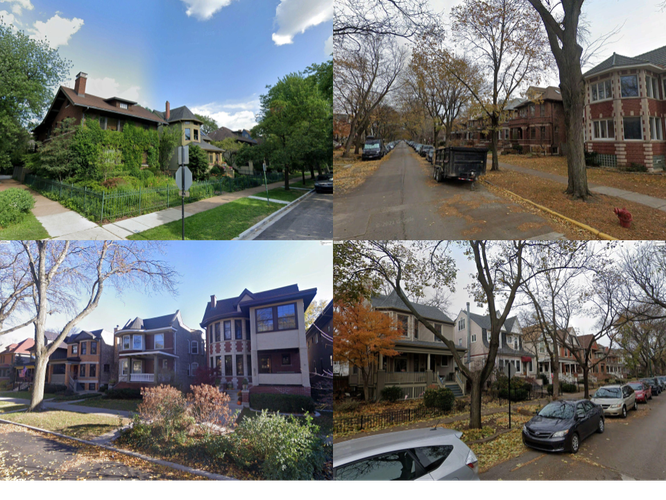

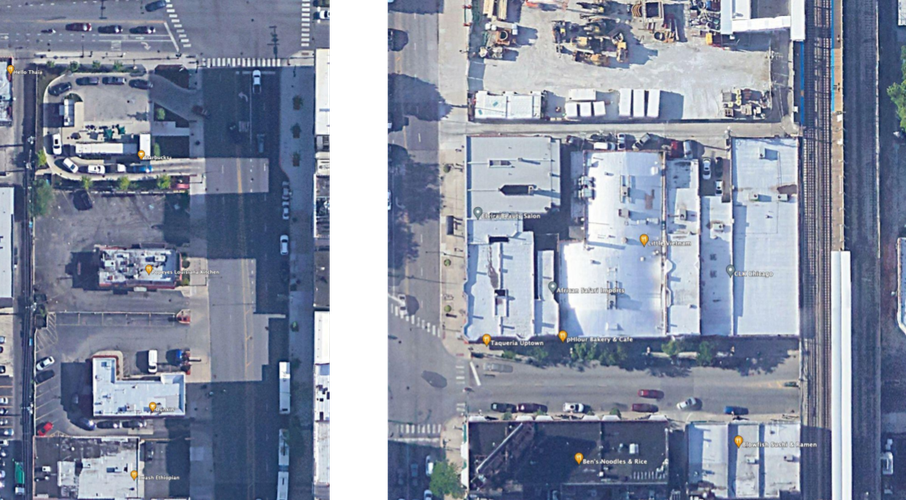

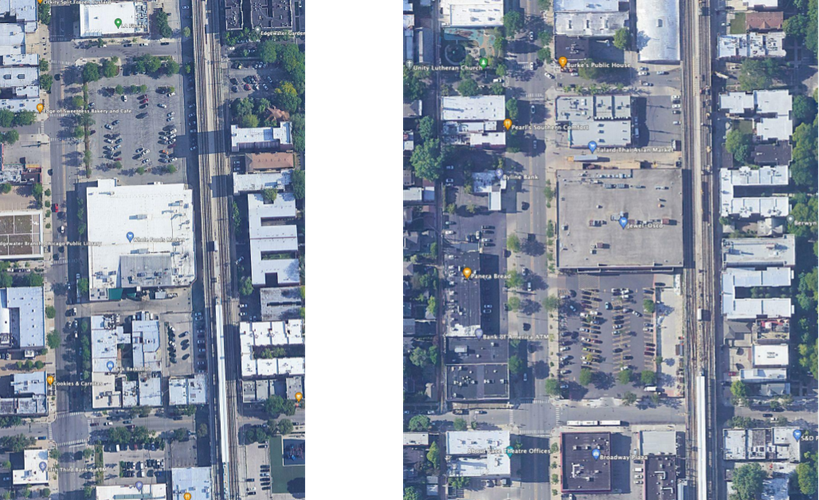

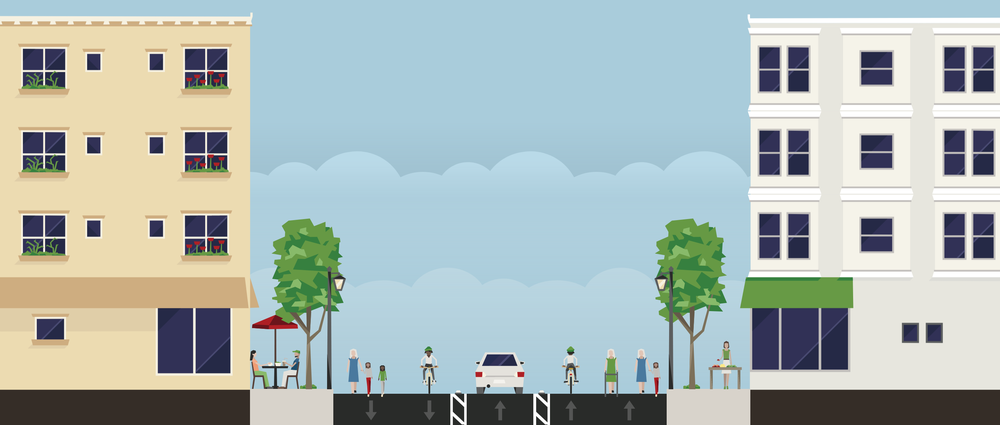

Housing in Edgewater is also varied throughout subsections of the neighborhood, creating a mixed identity within small areas. Locations closer to the beach have their own architectural style, large high-rise condo buildings, balconies, and bright colors. This area is often deemed “Edgewater Beach,” which connects to earlier ideas surrounding the strong connection between this area and its proximity to the lake. To the west of the Edgewater Beach area, between Sheridan and Broadway, much of the housing takes the form of apartment buildings with three to four stories. Many of these buildings share a similar form and image and create another sub-community that is referred to as “Edgewater Proper” given its proximity to the city center and its concentration of population. To the northwest of Edgewater Proper, many of the multi-family apartment buildings become single-family homes, making way for a third subcommunity referred to as “Edgewater Glen.” This area is home to many families, has some of the lowest population densities in the neighborhood, and is one of the farthest areas from the center of Edgewater. These characteristics have similarly separated this area of Edgewater from the rest. This separation of housing types is seen in the diagram below provided by secondcityzoning.org which represents zoning ordinances that separate Edgewater into areas where multi-family homes are supported, townhouse and multi-unity facilities are supported, and where single-family homes are supported. The incongruity between these areas limits the strength of neighborhood identity within Edgewater as each of these areas has developed its own idea of community. Harsh boundaries created by roads have also made each of these communities isolated within themselves, limiting frequent interaction between each sub-community on a regular basis.

-- Neighborhood Diagram --

Social Mix

General Neighborhood Statistics::

(With city-wide and regional data provided as reference)

Neighborhood Age Statistics::

Neighborhood Family Distribution::

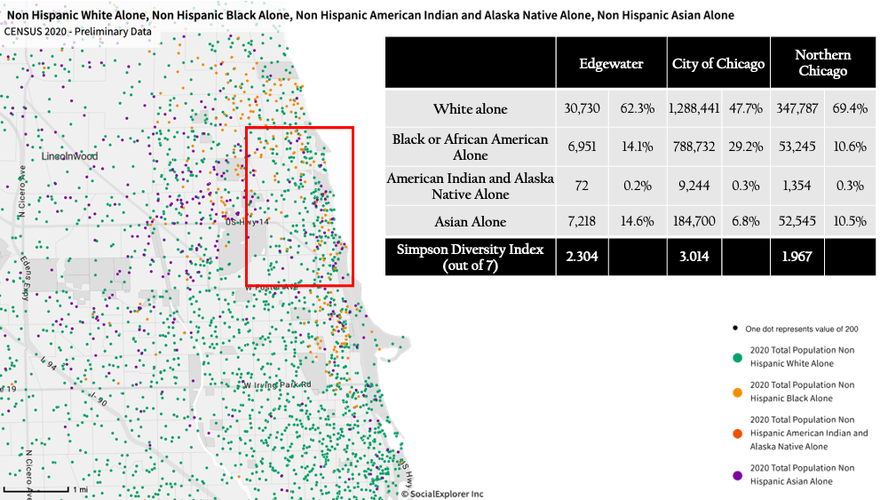

Race distribution with Simpson Diversity Index::

Property value distribution with Simpson Diversity Index::

Housing type distribution with Simpson Diversity Index::

Upon first glance at Edgewater’s primary statistics, the neighborhood is clearly very dense, especially in comparison to Chicago and its subregion. It is over three times as dense as the City of Chicago, and about 1.5 times as dense as its fellow North Side neighborhoods. Being a neighborhood nearly eight miles from the downtown area of Chicago, this density is unexpected, yet this density seems to have interesting implications for the neighborhood’s diversity. First looking at the distribution of races around Edgewater, the neighborhood has a relatively wide array of racial representation, especially in comparison to other neighborhoods on the North Side of Chicago. The Simpson Diversity Index shows that the racial diversity in the neighborhood is 2.3 out of 7, which is a low score, but still around 0.4 higher than the surrounding neighborhoods. Looking closer into racial breakdowns, this is likely because of the Asian population, which accounts for 14% of Edgewater’s population, a percentage twice as high as Chicago as a whole. Edgewater is also 14% black, a percentage 4% greater than the North Side as a whole. Despite this, Edgewater still houses an overwhelming majority of white residents who make up around 62% of the neighborhood. Edgewater’s racial distribution is far from being perfectly diverse, however, it shows a level of diversity that other neighborhoods in the area were unable to foster. This is possibly due to the influx of minority residents during the housing shortage in the 1940s and 50s which attracted residents to the Edgewater neighborhood due to its availability of high-density housing. Along this line, the data above shows that Edgewater has an interesting distribution of housing types. It is far less diverse than Chicago and its region in this regard, scoring a 3.9 out of 7 on the Simpson Diversity Index while Chicago and the North Side scored 5.4 and 6.0, respectively. It seems this is primarily due to the large percentage of housing units that house 50 or more residents in Edgewater, a group that makes up 43% of Edgewater’s renter-occupied housing. In Chicago and on the North Side, this metric is a mere 19.1% and 25.4% respectively. The availability of high-density housing helps reconcile how Edgewater has achieved its high population density and attracted minority groups to the neighborhood in the mid-nineteenth century.

Another aspect of Edgewater’s demographic data which is interesting is the lack of diversity within the values of properties. After calculating the Simpson Diversity Index on the ranges of housing values in Edgewater, it was found that it has a relatively homogenous housing market, with an index of 4.062 on a neighborhood level as compared to an index of 4.982 on a regional level. This lack of diversity seems to primarily account for the large majority of properties within the price range of $150,000 to $299,999. Out of Edgewater’s owner-occupied housing, 41.8% of the properties are within these values, whereas on the North Side, only 27.3% of the owner-occupied housing falls within this range of values. On top of this, Edgewater has higher percentages of houses that fall in the ranges of prices below $150,000, whereas the region has a higher percentage of houses whose values are in ranges above $299,999. Edgewater lacks the wide variety of housing values that its region exhibits, yet its housing values tend to fall primarily in the lower-to-middle ranges.

When it comes to other demographic measures, such as family structure age distribution, Edgewater shows similar trends to its region, and Chicago as a whole. For example, the Simpson Diversity Index of the distribution of family structures in Edgewater and Chicago are 1.799 and 1.851 respectively on a scale of three. This level of diversity within family structures is actually quite impressive, given that the entire city of Chicago is a large area with many different groups of people and family structures, yet Edgewater is able to maintain similar levels of familial diversity on a much smaller scale. The same goes for the age distribution of Edgewater, as it has cultivated an age demographic very reminiscent of the overall composition of Chicago, with no clear majorities in its age groups, and a relatively even distribution of ages across the population. These demographic realities show that Edgewater has maintained a healthy diversity in family structure and age, two elements crucial to maintaining a prosperous community.

Note: demographic measures come from a 2020 ACS 5-year estimate survey accessed through Social Explorer.