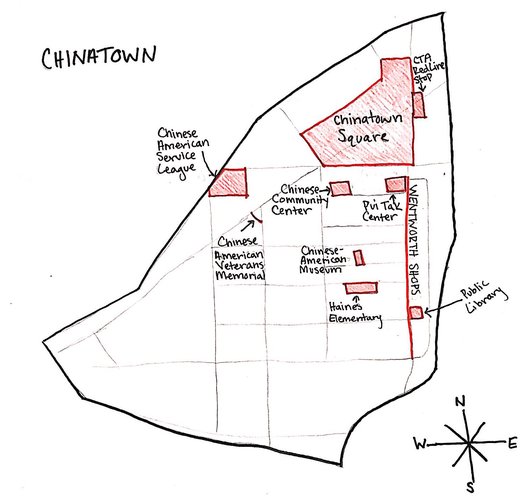

Overview

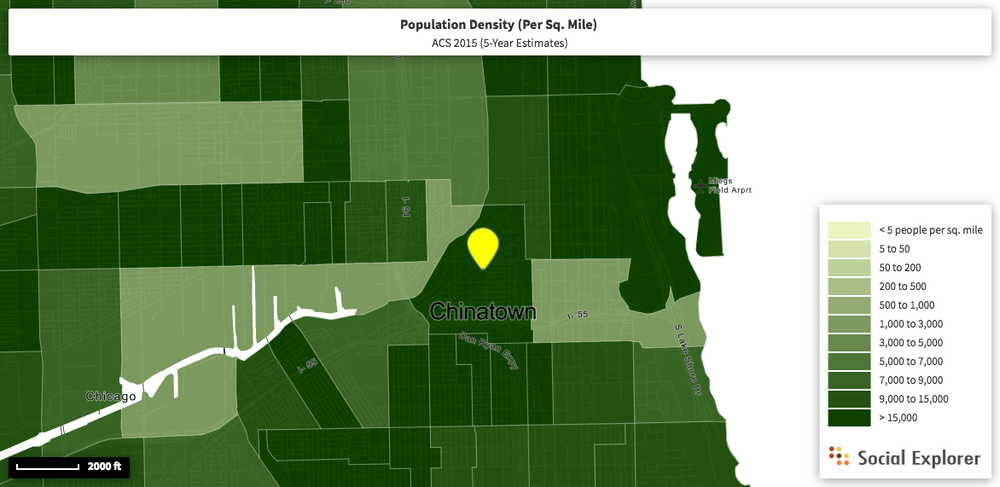

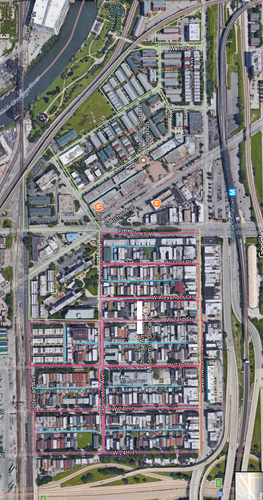

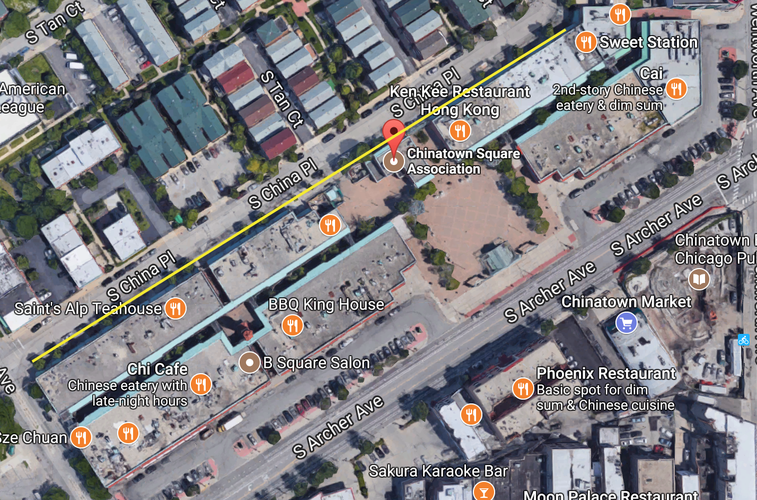

This map depicts population density by census tract. Most

neighborhoods do not align with their census tract. However, Census Tract 8411

aligns nearly perfectly with Christopher Devane’s delineation of Chinatown.

There are only slight differences is the northern and western boundaries. The

census tract has the northern boundary at W 18th Street and Devane has the

northern boundary at W 19th Street. This difference should not

affect the population count or population density because the blocks between W 18th

and 19th Street are mostly parking lots and nonresidential areas. The census tract has the western boundary just past Grove Street while Devane has

the western boundary one street farther east on S Tan Street. This difference

should also have little effect on the population count or density because Grove Street is not

residential.

Chinatown has a population of 7,673 people and a population density of 17,382.9 people per square mile, which makes it one of the more densely populated neighborhoods of the city. Chinatown is more densely populated than the Lower West side to the west (2,276.6 residents per square mile), the Near South Side, the South Loop to the northeast (about 14,000 residents per square mile), and Pilsen to the northwest (about 13,000 residents per square mile). Chinatown has a similar population density to Bridgeport to the south (about 15,000 residents per square mile).

Chinatown has a geographical area of approximately 294 acres

or .46 square miles using Census Tract 8411 delineations. This size is on the smaller

side for Chicago neighborhoods, but the area is densely packed with residents

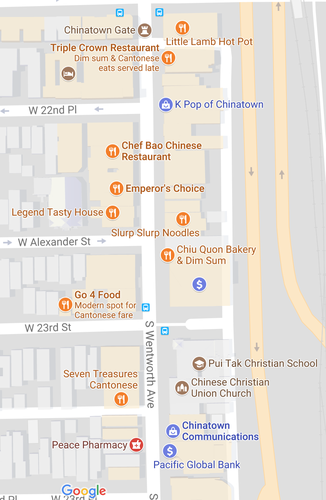

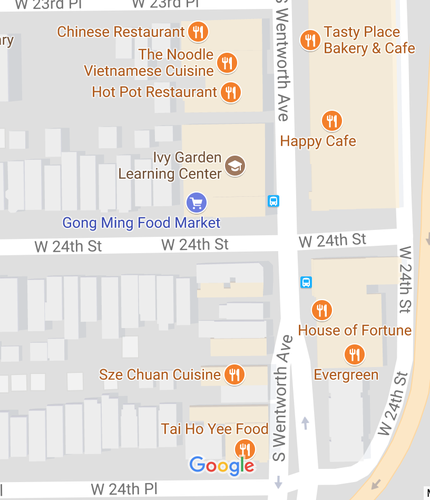

due to the prevalence of apartment-style housing. Chinatown is a relatively residential area, but it maintains a strong commercial character as indicated by the bustling shops and restaurants all

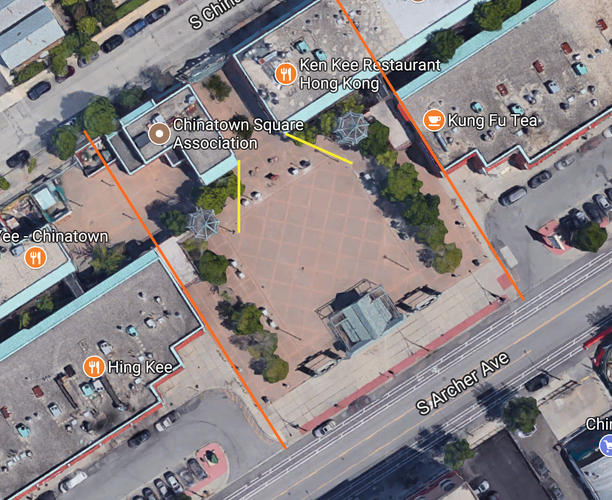

along Wentworth Avenue and in Chinatown Square on the north side of the

neighborhood.

Chinatown has an impressive coherence, culture, and identity.

The neighborhood does an excellent job of balancing commercial tourism and densely packed residential areas. One might think that it would be difficult to

balance the constant presence of tourists and outsiders within a community. However,

the economy of Chinatown is largely dependent on this tourism and therefore the community must briefly integrate these visitors into their home.

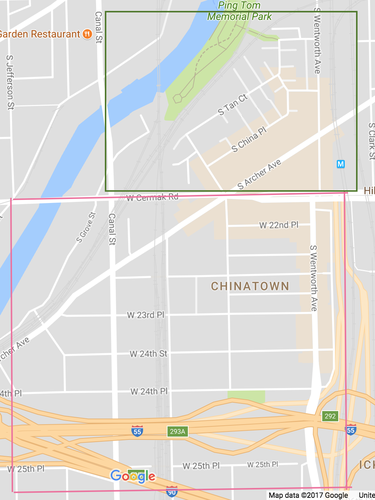

The delineations of the neighborhood make use of natural fixtures, wide

streets, and transportation markings.

These strong delineations also contribute to the strong coherence of the neighborhood.

One aspect of Chinatown’s strong is its residential area. Pedestrians are present in all parts of the neighborhood. It is not uncommon to see elderly women walking up and down, quieter, residential streets of the neighborhood. Parents can be seen pushing strollers up and down walkways. A Chinese Community Center is present on 22nd Place, displaying Chinese and American Flags strung along the entrance. The building mixes Chinese and American architecture to create a warm, inviting ethnic character.

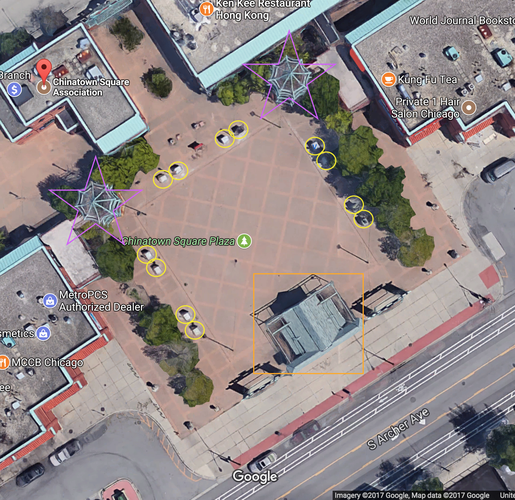

The coherence of the community is evident in the commercial section of the neighborhood. Every store sign is written in both Chinese and English, even the Walgreens. Aside from the Walgreens, Starbucks, and a handful of banks, each of the stores and restaurants in the community cater to the culture of their Chinese residents. On every commercial street, there is at least one Chinese medicine shop, Chinese bakery, Chinese restaurant, and small corner store stocked with Chinese brands. The architecture of nearly all commercial and retail buildings has a hint of Chinese style, whether it be a gargoyle, pagoda, or a fence on a porch.

These architectural accents and shop signs make the borders of Chinatown clear. Once one moves south of I-55, shops with signs in Chinese become sparse and then stop all together, giving way to other shops and restaurants. Each of the larger commercial areas, such as the entrance to Wentworth Ave, has a large gate reading “Welcome to Chinatown.” Likewise, the main public area, Chinatown Square, also has two gates on both the northern and southern entrances. The Northern border of W 18th or 19th Streets are appropriate because there is a border of large parking lots between Chinatown and the neighborhood to the North. The River is an excellent natural border to the West because there are few convenient places at which to cross it. The eastern border of Clark St is strong because that is the street that the ‘L’ Red Line runs along. The southern border is a bit trickier to define due to Chinatown’s growth and expansion in Bridgeport. The delineation is less clear, but it appears to be around W 26th St if one looks to shops and signs as indicators. The strength of coherence and clarity of delineation are evident to anyone who visits Chinatown.

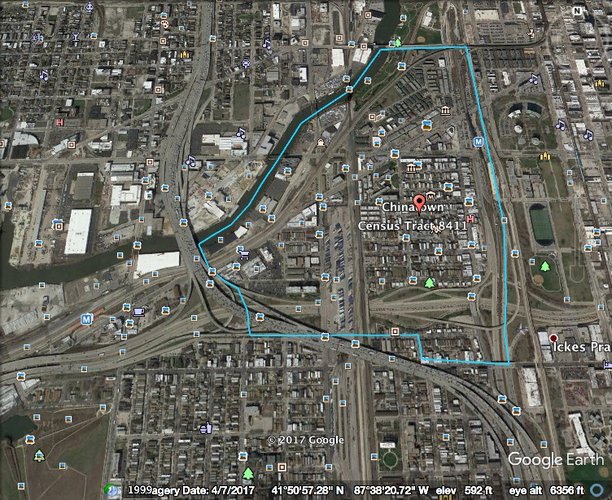

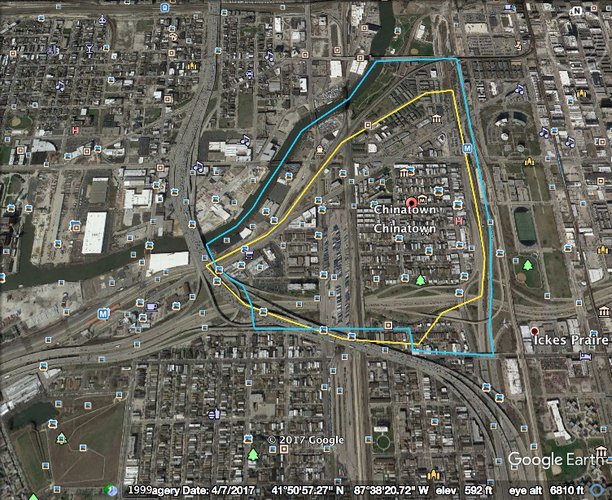

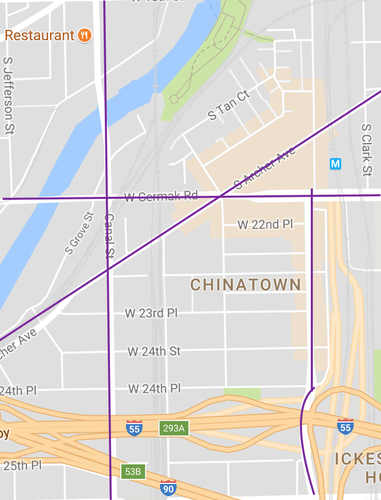

Layers:

As previously stated, Chinatown is one of few Chicago neighborhoods that very nearly matches a census tract. Census Tract 8411 is represented by the blue outline and Christopher Devane's delineation of Chinatown is represented by the yellow outline. There are very few discrepancies between the two delineations. This similarity speaks to the clarity of Chinatown's borders.

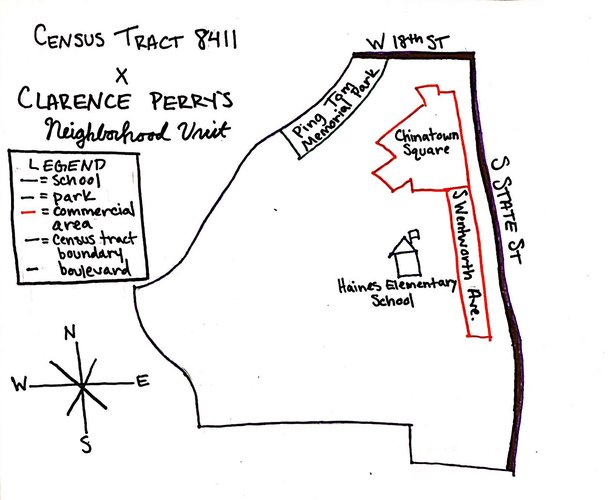

This map layers the delineation of Census Tract 8411 with aspects of Chinatown that align with Clarence Perry's theory of a Neighborhood Unit. The map depicts a central elementary school, significant park area, large boulevards along the border, and commercial space along the perimeter of the neighborhood.

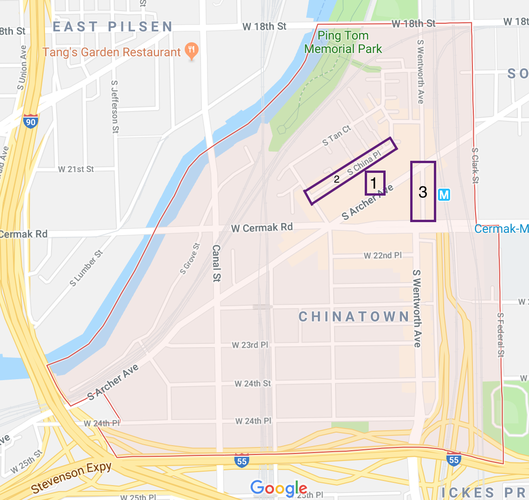

Diagram:

Chinatown was settled around Cermak and Wentworth in 1912. Prior to 1912, 25% of Chicago’s 600 Chinese residents lived between Van Buren and Harrison St in the Loop. However, a variety of circumstances including expensive rent, discrimination, overcrowding, and crime led these residents to migrate south to the Armour Square community area.[1]

The settlement of modern-day Chinatown was not spontaneous. The initial movement from the Loop to Armour Square was spurred by the On Leong Merchants Association, which commissioned the construction of a building along Cermak that could house 15 stores and 30 apartments meant for Chinese use.[2] The building was not constructed in strict Chinese architecture, but has hints of Chinese style. This movement was the seed from which all of Chinatown grew. The ethnic neighborhood of Chinatown expanded from this singular building. The residential areas of Chinatown spread southwest of Cermak and Wentworth and the commercial areas of the neighborhood continued growing along the streets of Cermak and Wentworth. In the late 1980s, businessmen further developed the area to the north of Cermak by erecting new housing options, particularly townhouses, and creating “Chinatown Square,” a public area and shopping mall/dining center just south of the new housing. The development of Chinatown can be organized into two time periods: its initial growth in the early twentieth century and its subsequent expansion to the north in the late twentieth century. There may be a third time period in the making as Chinatown is growing quickly and beginning to expand south into Bridgeport.

Accessibility to Chinatown has grown since 1969 when the Dan Ryan section of the L’s red line was opened. Although this train stop was not present when the neighborhood was first settled and therefore did not significantly influence its inception, this train stop has helped the tourism of the neighborhood flourish. People from all over the city have the ability to reach Chinatown via public transportation, boosting Chinatown’s economy, which is largely dependent on tourism.[3]

As noted in the “Layers” section, the layout of Chinatown very nearly matches Clarence Perry’s seminal model of The Neighborhood Unit. It is possible that the neighborhood developed in this way for a number of reasons. One of which is the presence of already-existing wide boulevards around the perimeter and the permanence of the Chicago River. Another reason is the settlement of commercial areas along the border of the neighborhood, which had been planned in the neighborhood's initial inception. The neighborhood of Chinatown is served by only one elementary school, which is logically placed in the center of the community in accordance with Clarence Perry’s Neighborhood Unit. These characteristics of Chinatown arose out of a delicate balance between urban planning and natural growth.

[1] Kiang, H. (1992). Chicago's Chinatown. Retrieved from http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/284.html

[2] Encyclopedia of Chicago. (2005). On Leong Merchants Association Building, 1928. Retrieved from http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/11597.html

[3] Chicago Transit Authority. (2017). Red Line (‘L’). Retrieved from http://www.transitchicago.com/redline/

Social Mix

The data above compares the diversity of Chinatown with respect to race, educational attainment, and housing value against Armour Square (Chinatown's community area as well as region), and the city of Chicago. The Simpson Diversity Index measures how even the demographic distribution of an area is across "n" numbers of categories. When reading and analyzing Simpson Diversity Index values, it is vital that one takes into consideration the number of categories the Index is measuring. For instance, in the table above, race was analyzed with respect to 5 different categories, so each of the indices should be read as value out of five. The higher the value is, the greater the diversity within the area. The data shows that Chinatown is not very racially diverse, as indicated by its Simpson Diversity Index of 1.41 out of 5. Armour Square is slightly more racially diverse with an Index value of 2.00. The city of Chicago is the most diverse of the areas considered with an Index value of 2.26. In terms of educational attainment, Chinatown is far more diverse compared to the other areas considered. Chinatown has a Simpson Diversity Index value of 4.03 out of 7 compared to Amour Square's value of 1.29 and Chicago's value of 0.83. In terms of housing value, Chinatown is not very diverse according to the Simpson Diversity Index. Chinatown has a value of 2.89 out of 9 while Armour Square has an Index value of 3.11 and the city of Chicago has an Index value of 4.19. The Simpson Diversity Index shows that Chinatown is diverse in some aspects, such as educational attainment, but not as diverse in others, such as race and housing value.

All data for this section was provided by Social Explorer and the 2010 Census.