Overview

Size

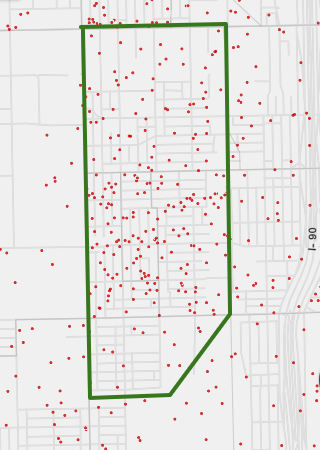

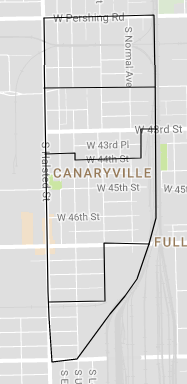

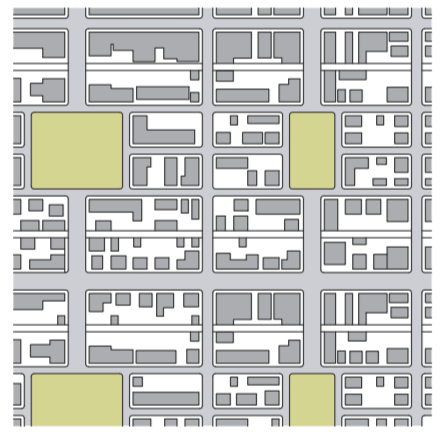

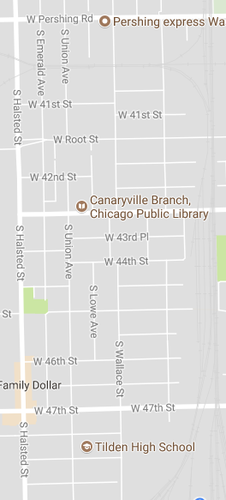

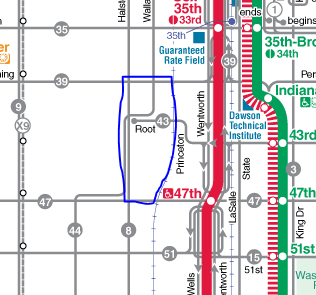

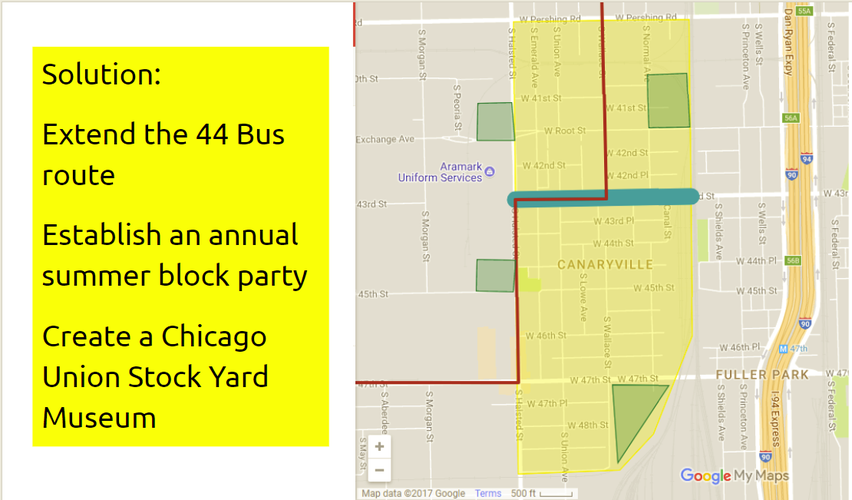

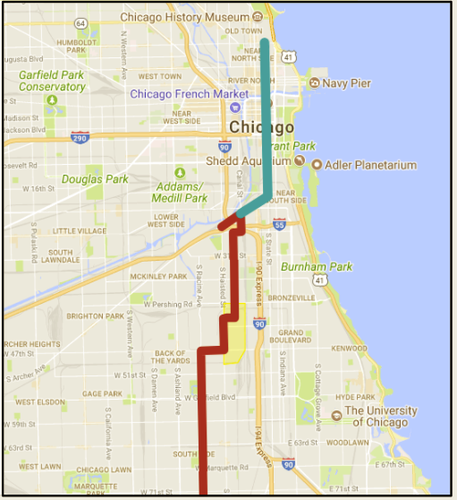

Canaryville has a population of about 6,480 people, according to Social Explorer (the green outline on the map above encloses Canaryville, and each red dot represents 25 people). The neighborhood covers 0.6 square miles, so it is easy to travel. The north end and the south end are 1.3 miles apart, and the east and west boundaries are separated by half of a mile; perhaps more pertinently, the neighborhood is thirteen blocks long and four blocks wide. The narrow nature of Canaryville fits it pretty nicely into Clarence Perry's ideal quarter-mile radius to a neighborhood, and well within Jane Jacobs' population target.

Identity

My walk around Canaryville gave me a strong sense that the neighborhood is a cohesive unit. It is delineated on two sides by wide through streets (South Halsted Street and West Pershing Road), while none of the internal streets running north-south are through streets: in fact, most of the internal streets are only a block long, leading to very light traffic within Canaryville itself and lending the space to a bustling scene of children playing and families walking to church on a bright Sunday morning.

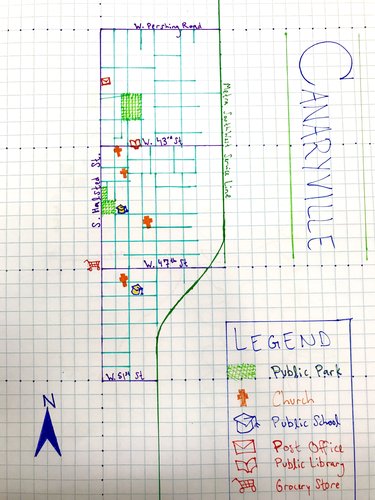

People were out using the public space, although there is not very much of it in Canaryville. Canaryville has only two small parks that I saw, and one is adjoined to the public elementary school. I noticed people caring for and about the public space, which says to me that they are invested in the neighborhood community and interact with their neighbors. Many of the houses I passed were decorated for Halloween in some way, although the holiday is still two weeks off; I imagine that these homes are expecting trick-or-treating neighbors, and decorating so far in advance to add fun and festive spirit to the streetscape shows care for neighbors. There was almost no litter on the sidewalks and streets, despite a total lack of garbage cans provided by the city. To counter this lack of garbage depositories, several houses I walked past had placed plastic bags over the fences surrounding their front yards for neighbors and passerby to put litter into. This extra level of care for the way the streets look indicated to me that people who live in Canaryville care about their community.

I saw other markers of community in the neighborhood. There were white plastic bows tied around fences and lampposts (both public and private property), which I believe to be vestiges of a recent festival for a Catholic saint. Irish Catholicism as an identity runs high in Canaryville, with many homes displaying a sign for a Catholic high school or a shamrock in their yard decor. Canaryville’s strong history as a home to public employees, specifically veterans, cops, and firefighters was made clear by several flags and signs honoring these groups, especially signs proclaiming that “Blue Lives Matter.”

The name “Canaryville” is also central to this small space, often lumped in with Back of the Yards and other white ethnic neighborhoods on the southwest side of Chicago. Most notably, many homes sported a super creepy sign in the window proclaiming “Canaryville Watch Group: We Call the Police!” I was honestly concerned that being a stranger wandering around taking photographs of people’s homes would earn me a conversation with a cop, but I imagine that the time of day combined with my race saved me from the Canaryville Watch Group’s ire. I was also worried about drawing glares as an outsider, but I experienced the opposite: people called out to greet me from their porches, wished me a nice day, and offered to hold the bus I was rushing towards as I left the neighborhood. While the watch group’s signage was the most prominent proclaimer of the name Canaryville, the Chicago Public Library’s Canaryville branch and the Canaryville Veterans’ Association also made the neighborhood’s name known. Unlike Bridgeport and the Yards, which have mixes of Polish, Chinese, Mexican, and other ethnic residents and have restaurants, shops, and houses of worship dedicated to these cultural groups, Ireland was the only motherland I saw claimed in Canaryville, and I saw it held with pride many times over. From what I saw on my brief stroll, this small neighborhood has clearly defined boundaries and a clear sense of its own history and culture.

Layers

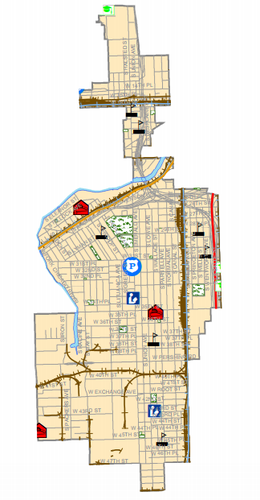

Because Canaryville is so small, both in terms of acreage and population, it is often part of a larger chunk of the southwest side when Chicago is split up into parts (as in Community Areas and aldermanic wards). Above is one instance in which Canaryville is split up rather than being entirely included in one part of the city: four different elementary school districts encompass different parts of Canaryville. Each of these four elementary schools also draws students from other surrounding neighborhoods, and only one of the schools (Graham School) is actually located in Canaryville itself. A single public high school, Tisdale High School, serves all of Canaryville, although it is popular in the neighborhood to school children in Catholic parochial schools. Only one parish, St. Gabriel's, is located within the boundaries of Canaryville, but many other Catholic churches are within close range. Canaryville is encompassed entirely within the eleventh aldermanic ward, along with good-sized parts of Bridgeport and Back of the Yards.

A Brief History of Canaryville

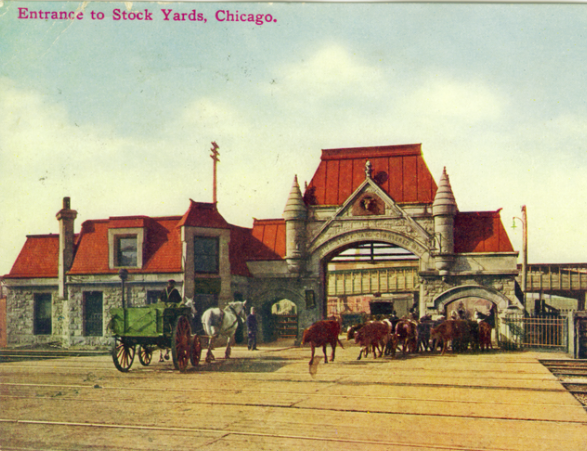

Although culturally distinct from other neighborhoods in the New City community area of Chicago, Canaryville shares history with Back of the Yards in that it was originally populated by Union Stockyards workers from the 1860’s until the decline of the meatpacking industry in Chicago sparked by wartime stress on factories and increased pressure on the industry to treat its workers better and improve its sanitation standards. After the jobs in meatpacking plants began to disappear, the leading employers of young Canaryville men were the United States Armed Forces and the city of Chicago, which employed Canaryville residents mainly as first responders like police officers, firefighters and EMTs.

Because of the high proportion of Canaryville breadwinners who were employed by the city, it was one of the South Side neighborhoods that did not experience White Flight in the years after the Supreme Court’s decision to deem racial restrictive covenants unconstitutional in 1948. Because the residents of Canaryville made modest incomes, and because many were required to reside within the limits of the city of Chicago in order to maintain their jobs with the police or fire departments, Canaryville remained almost entirely white throughout the twentieth century and is still strongly Irish Catholic today. Since people selling their Canaryville homes were legally disallowed from restricting the buyers to white people, but the residents were racist and did not want Black neighbors, teenagers and gangs in Canaryville resorted to racial violence in order to scare Black people away from their neighborhood, which is just west of the CTA Green Line from Black neighborhoods like Bronzeville and Washington Park. As recently as 1989, a group of white teenagers attacked a Black teen who was passing through Canaryville, and on my reconnaissance over the weekend I noticed a faded confederate flag.

I have heard three tales of how Canaryville got its colorful name. The first is that canaries lived in this part of Chicago before it was densely populated, picking over scraps from the Union Stockyards and the train cars passing on what are now the tracks for Metra’s SouthWest Service line. Another origin story derives from “canary” as a nineteenth century slang word for a tough teen, the kind who lived in this part of Chicago and joined one of the gangs that roamed the Southwest side. My favorite is the story that claims that when Appalachian coal miners moved from West Virginia to Chicago to work in the stockyards, others nicknamed their home after the canaries that would be the first voyagers into a coal mine to check for deadly gasses. The fact that the origin of Canaryville’s name is no longer known is a testament to the long history of this neighborhood and how it has endured as a distinct cultural community despite its size.

Works Cited

Archdiocese of Chicago. "Parish Finder." Accessed October 16, 2017. archchicago.org/parish-map.

Barrett, James R. "Canaryville." The Encyclopedia of Chicago. Accessed October 12, 2017. encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/2476.html.

Barrett, James R., and David R. Roediger. "The Irish and the" Americanization" of the" New Immigrants" in the Streets and in the Churches of the Urban United States, 1900-1930." Journal of American Ethnic History 24, no. 4 (2005): 3-33.

Chicago Public Schools. "CPS School Locator." Accessed October 15, 2017. cps.edu/map.

City of Chicago Office of the Mayor. "Wards Overview Map." Accessed October 15, 2017. cityofchicago.org/content/dam/city/about/banners/WardsOverviewMap.pdf.

Davis, Myron. “Canaryville.” University of Chicago Research Paper, doc. 1a, in “Documents: History of Bridgeport.” 1927. Chicago Historical Society.

Papajohn, George. "Racial Tension Fact of Canaryville Life." Chicago Tribune, August 18, 1991. articles.chicagotribune.com/1991-08-18/news/9103010300_1_black-em-flats.

Shanabruch, Steve. "Canaryville." Accessed October 11, 2017. thechicagoneighborhoods.com/Canaryville.

Social Mix

Simpson Diversity Index Table

Canaryville New City community area Southwest Side of Chicago Chicago as a whole

Income (out of 4) 3.814886 1.071513 3.411312 3.950868

Age (out of 4) 3.173016 3.405319 3.46969 3.453295

Race (out of 5) 1.626438 2.720484 3.164233 2.852888

Diversity Analysis

When I completed my initial reconnaissance of Canaryville last week, I came to the conclusion that Canaryville is not diverse: it has a strong ethnic identity as Irish, a strong racial identity as white, and a strong religious connection to Catholicism. After class discussion and after crunching the numbers, I can see the ways in which Canaryville is diverse after all. First of all, while it is firmly middle/working class in its identity, Canaryville has families with a range of incomes. This is represented in the high Simpson Diversity Index score the neighborhood receives for income level, and is underlined by the mix of single- and multiple-family homes and by the near-even split between renters and owners residing in the community’s houses. While I did not create a table that included Hispanic and Latino heritage, I believe that many people in the “Other” and “White categories in the race table identify such, and this makes Canaryville a bit more diverse ethnically than is represented in the table. I chose not to include Latino ethnicity because, being a white Latina myself, I believe that the structural discrimination against Latino communities stems more from many being racially Mestizo rather than from ethnicity, and I believe this is captured in the race category. Canaryville also has a fairly even distribution of age groups, although it skews young; perhaps there are not health or social resources nearby for seniors, making it difficult to “age in place.” While Canaryville has these elements of diversity, its identity as a white Irish Catholic neighborhood makes it hostile for people who do not fit into this category, from what I have read. I would say that Canaryville has the kind of diversity needed for a functional neighborhood, but not the kind of diversity we strive for as planners and as citizens of Chicago.

Note: all statistics and demographic measures come from a 2015 ACS 5-year estimate survey. I accessed them through Social Explorer. The works cited in the Overview section also informed my findings in this section.