Overview

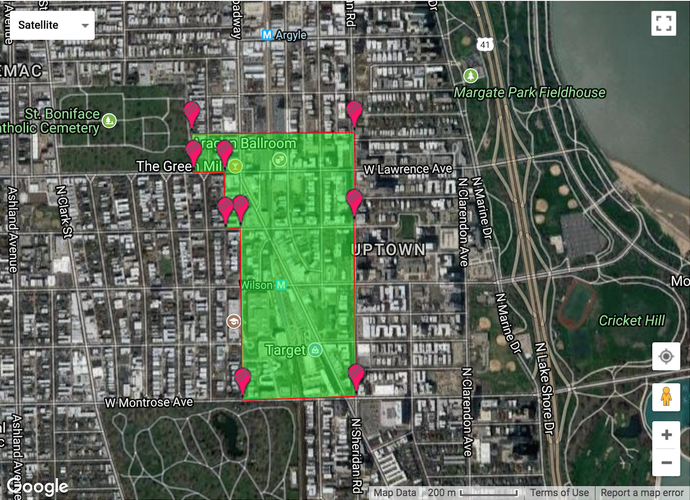

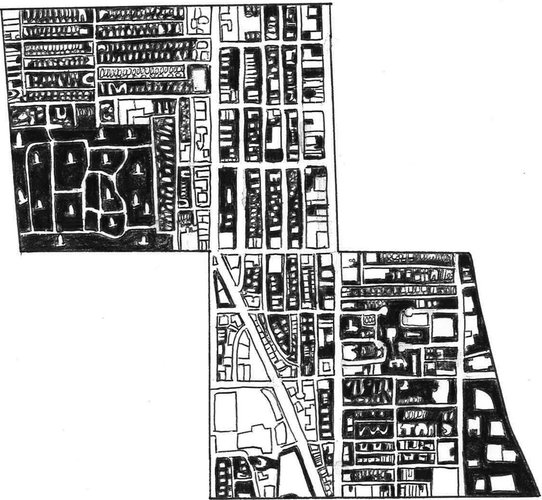

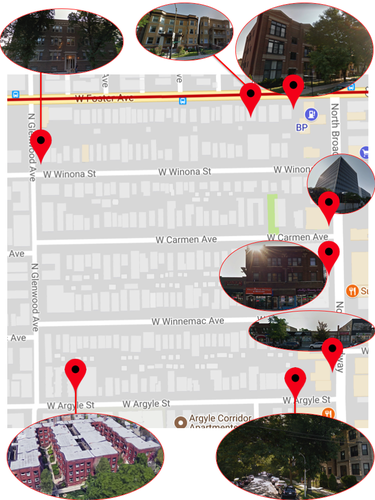

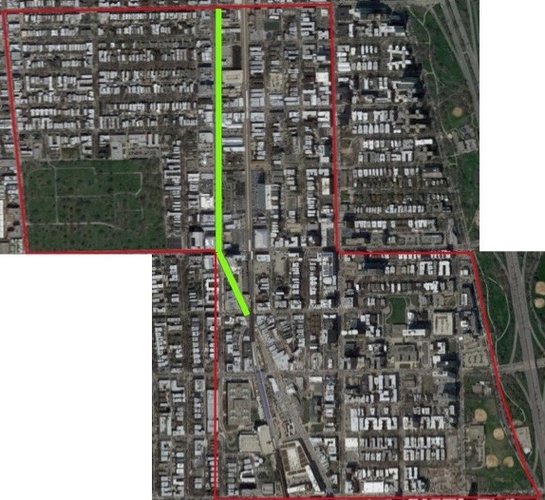

Uptown Square has a population density of 10,598.2 per square mile. With a geographic size of 102.77 acres, or 0.16 square miles, its total population density is roughly 1,695.712. I would characterize the size of Uptown Square as a bit larger than an average public high school in Florida, according to the National Center for Education Statistics.

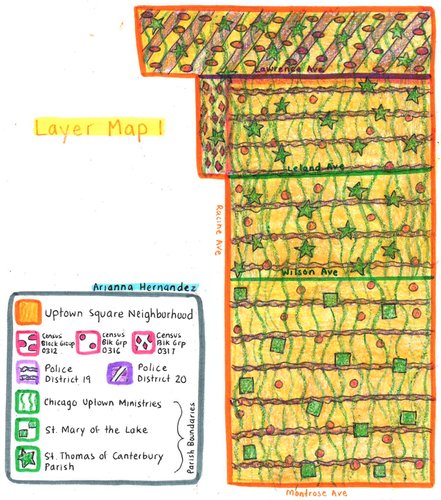

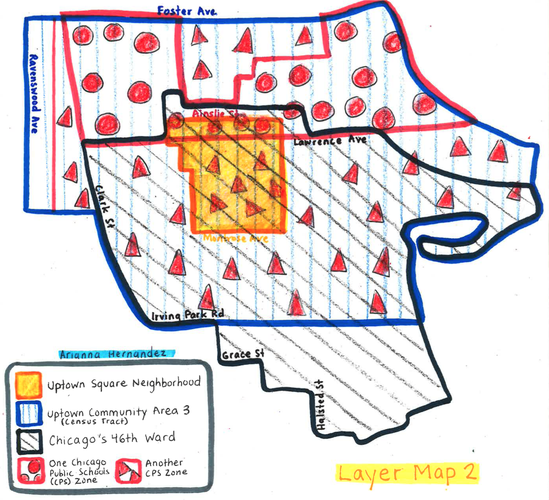

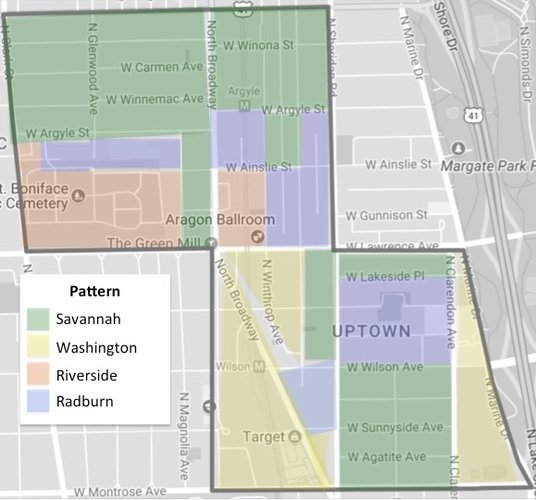

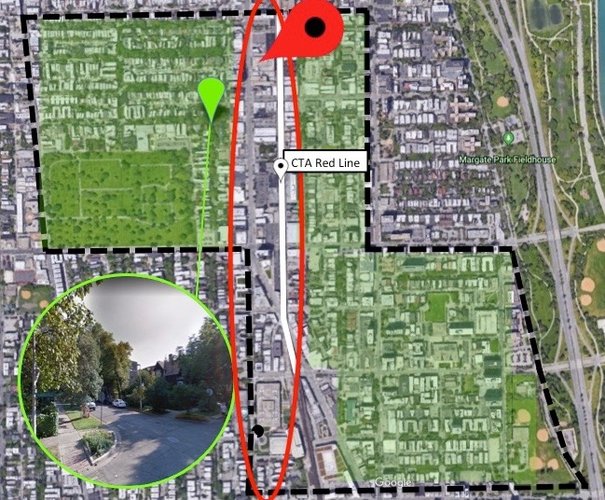

Uptown Square has a quality of forming a unified whole. As I walked throughout the neighborhood, I noticed that the name “Uptown” is ubiquitous in signage, banners, and shop names. The name “Uptown” is most likely an abridged version of “Uptown Square.” For example, there is a street banner that says “Uptown Square,” but the “Uptown” lettering of the banner is significantly larger than the “Square” portion. When one explores Uptown in a search engine, mixed results appear, some speaking of it as a community area and many regarding “Uptown” as a neighborhood although they may be referring to a shortened version of “Uptown Square.” My findings suggest that Uptown is a community area containing six neighborhoods, Uptown Square being one of them. It seems that Uptown Square in Uptown has an inherent definitional problem because it can be unclear which particular “Uptown” one is referring to, the community area or the neighborhood.

One may ask whether the other neighborhoods in Uptown demonstrate the same sense of coherence, and I would say no. Because Uptown Square is a vibrant commercial area, rich with historic buildings, and a multiethnic dining scene, it appears that Uptown Square is the entertainment destination (capital, if you will) of the community area of Uptown, whereas the community’s other neighborhoods have their own sense of identity. For example, residents of Buena Park, strongly associate with their own neighborhood name when giving titles to businesses, for instance. While residents of Buena Park may identify as members of the Uptown community, their own neighborhood culture and history would ultimately rule over the possibility of identifying with the Uptown community alone.

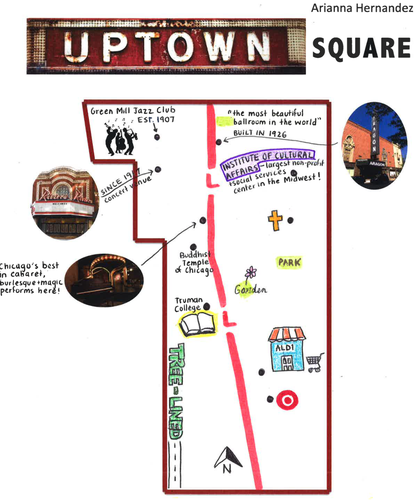

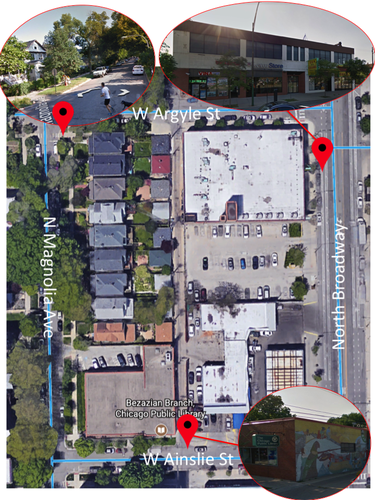

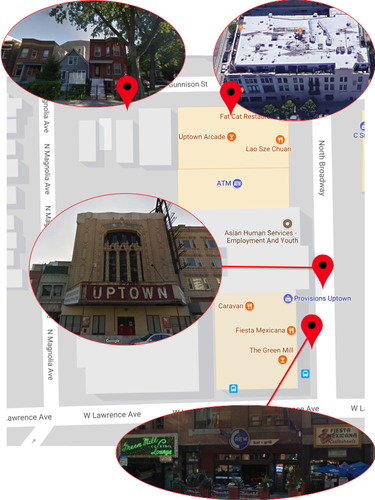

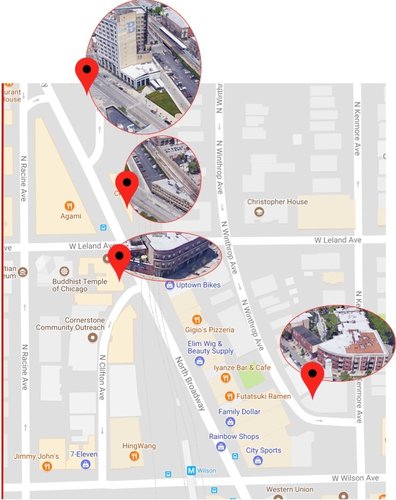

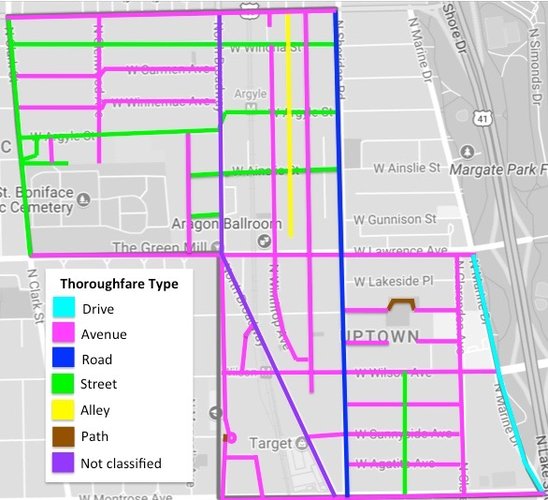

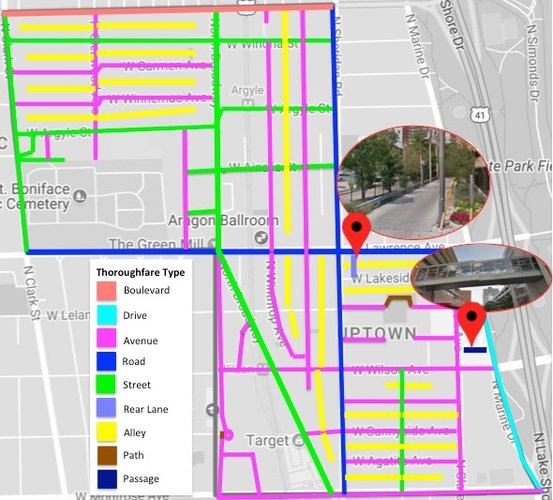

In 1900, the Northwestern Elevated Railroad built a terminal in Uptown at the intersection of Wilson and Broadway (now a stop in the CTA Red Line). For a while, Wilson and Broadway was the last stop for all northbound elevated trains coming from downtown Chicago. This station had an enormous impact on the development of Uptown, one way being that Uptown became a vacation destination for Chicagoans who lived farther south. Around 1910, the popularity of a shop called Uptown Store, owned by Loren Miller, gave the community its name. By the mid-1920s, the concentration of retail and recreation around the crossroads of Broadway and Lawrence obtained the name Uptown Square. Although the neighborhood area of Uptown Square is not actually a square, the name was given in reference to the sense of commercial activity that takes place in a market square.

The community area now known as Uptown was originally outside the city limits of Chicago and constituted part of Lake View Township, established in 1857. Uptown Square was developed throughout the first two decades of the twentieth century by real estate, which transformed the countryside crossroads of Broadway and Lawrence to a bustling entertainment district. It is clear that Uptown Square’s development was related to the aforementioned transit line stop because after its construction, the community received an influx of residents, more than doubling its population between 1900 and 1910. Larger, multi-story apartment buildings took the place of single-family homes.

Entertainment venues glamorous and great in size, such as Riviera Theater and the Aragon Ballroom, were constructed just in time to house jazz artists among others in time for the “roaring twenties.” The Uptown neighborhood experienced great prosperity in the housing industry. As interest in motion pictures, social dancing, and a new culture of consumption grew through the 1930s, Uptown was a prosperous and flourishing neighborhood known for its bright lights, theater scene, and exquisite selection of shops and restaurants.

In The Everyday Neighborhood, Professor Talen mentions that a purpose of neighborhoods is to unite the lives of its inhabitants and one way to do that is through its offerings. Uptown Square, with a glowing public space, dance halls, concert venues, retail centers, all within a three-block radius, contributed to an atmosphere that truly manifested “the basis of urban experience” in its early years. Uptown Square offered a great pool of jobs and goods to the people, an important feature according to Jane Jacobs in The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Moreover, The Neighborhood and the Neighborhood Unit suggests that because cities are mobile, neighborhood life typically loses its character and the neighborhood ceases to be part of the “lovable whole.” Uptown Square seems to have only reaped more success in its prime as it invited city dwellers and folks from all walks of life to share in its fruits of pleasure and escape from the everyday monotony to a vibrant bubble. Uptown Square is unique in that it was not deliberately designed to accommodate people or provide community. Rather, it appears that its very beginning as an entertainment district magnetized the people to live there.

Uptown Square is designated as a Chicago Landmark, which speaks volumes to the significance of the neighborhood’s history and architecture to the story of Chicago. While Uptown Square has weathered changes over the years, a renewal is underway to restore its historic movie palaces and architectural gems, most of them dating back to the 1920s and 1930s.

Gorski, E. “Chicago Landmark Designation: Uptown Square District.” City of Chicago, Planning and Development, www.cityofchicago.org/city/en/depts/dcd/supp_info/chicago-landmark-designation--uptown-square-district0.html.

Jacobs, Jane. 1961. Chap. 6, “The Uses of City Neighborhoods” in The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Vintage. Pp. 112-142.

Mumford, Lewis. 1954. “The Neighborhood and the Neighborhood Unit.” The Town Planning Review 24, 4: 256–70.

“Rich History of Uptown Neighborhood Spans More than a Century.” Uptown Chicago Commission, 6ADAD, uptownchicagocommission.org/jun_13b_07.html.

Schlater, Angela. “The Bright Lights of Uptown.” The Bright Lights of Uptown | Edgewater Historical Society, Edgewater Historical Society, Aug. 2000, www.edgewaterhistory.org/ehs/articles/v11-4-2.

Talen, Emily. 2017. The Everyday Neighborhood (excerpts from forthcoming book Neighborhood, Oxford University Press).

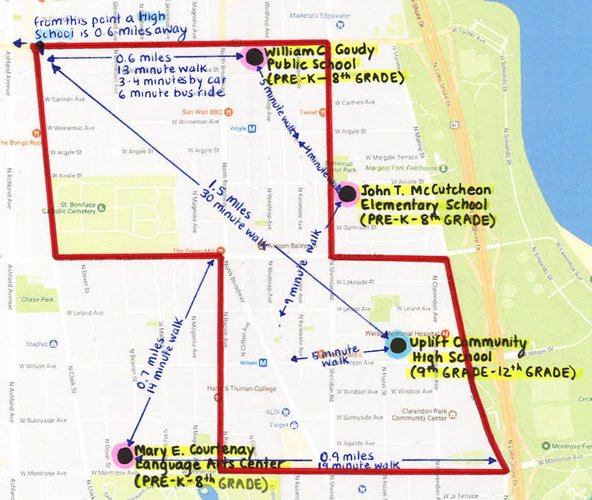

Social Mix

With regard to race/ethnicity, over half of Uptown’s population is white and about a quarter is African-American. Although this may appear to be non-diverse, when one considers the indices of the Uptown Community Area, North Region of Chicago, and the City of Chicago, Uptown is not only equally as diverse as the city, but also more diverse than the community area and region. Because of this, Uptown identifies as an ethnically diverse community although it scores a three on the Simpson Diversity Index with seven different categories. In regard to age, more than 50 percent of Uptown’s population is between 25 and 54 years old. There are not many children in Uptown as 55 to 64 year-olds are more numerous than individuals ages 17 and under. According to the indices for age, Uptown has similar diversity to the North Region, and is less diverse than Chicago. It is possible that a strong presence of entertainment venues and nightlife may be more appealing to single adults than families with young children. In relation to educational attainment, the Uptown neighborhood and community area is almost as diverse as Chicago and slightly more diverse than the North Region.

The concept of diversity is complex because even with an apparently low Simpson Diversity Index, a neighborhood can still be diverse by comparison to its surroundings. Moreover, I understand diversity as a sliding scale and not binary. For example, I could describe Uptown as less diverse than Chicago, but it may be very diverse in comparison to another neighborhood with a virtually homogenous (on paper) population. Therefore, when analyzing characteristics of a neighborhood for diversity, it is necessary to recognize the context and factors that may influence the diversity.