Overview

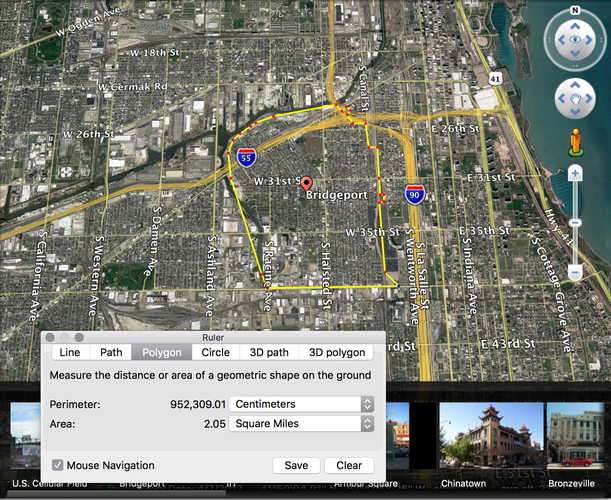

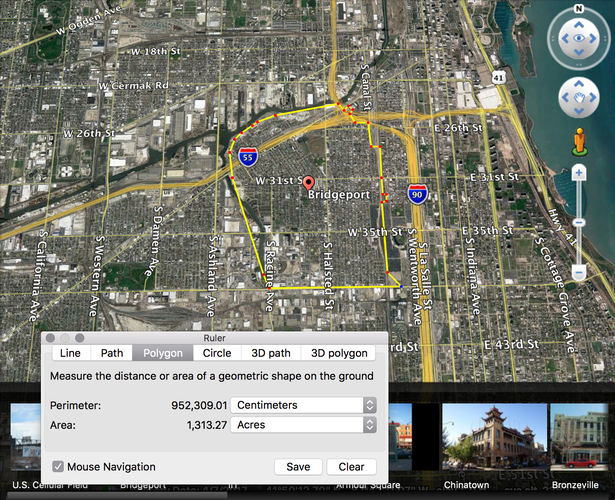

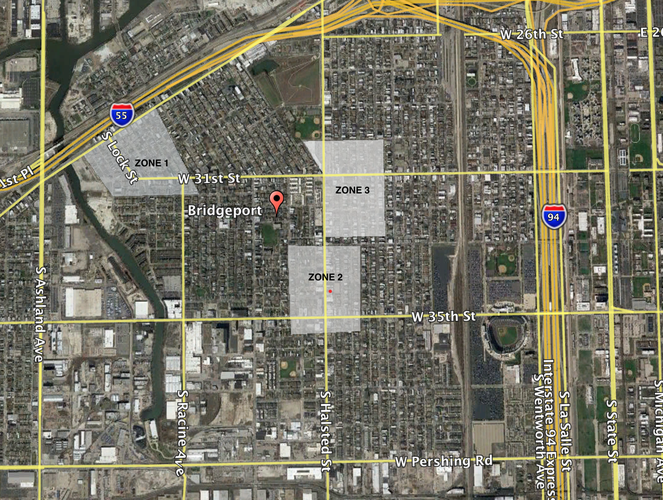

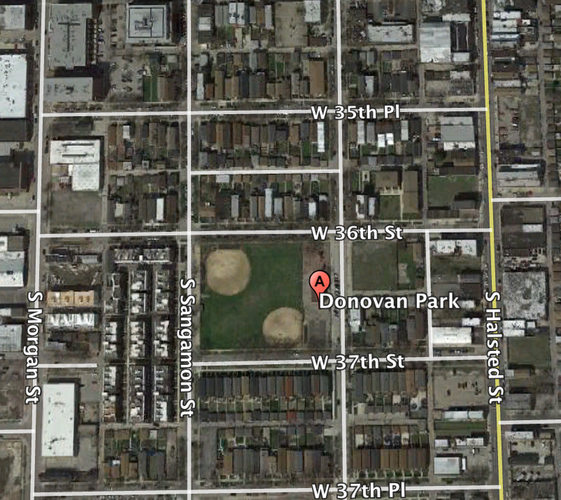

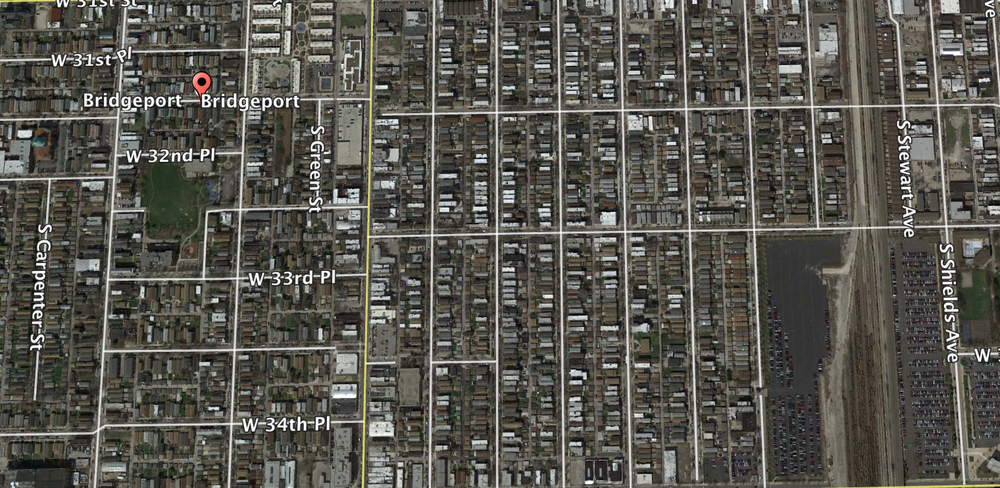

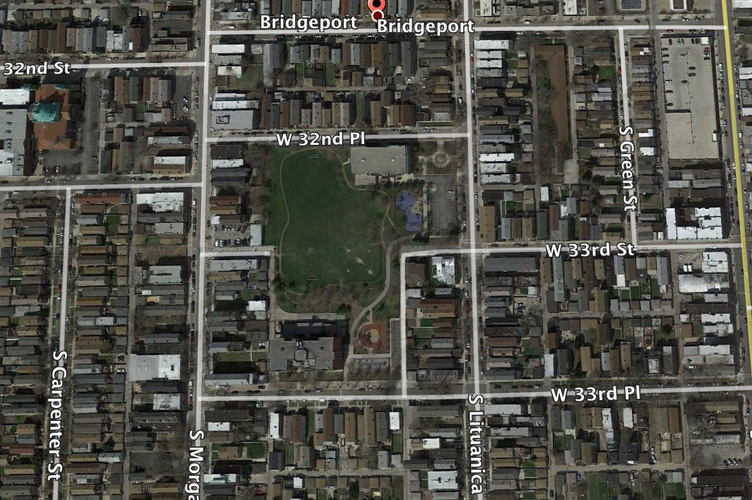

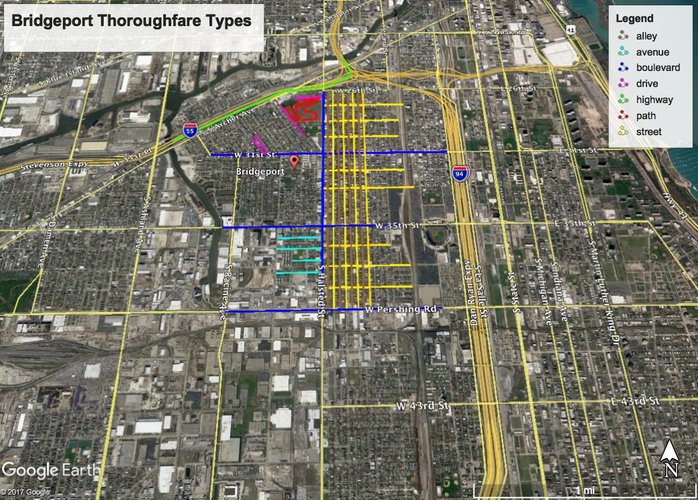

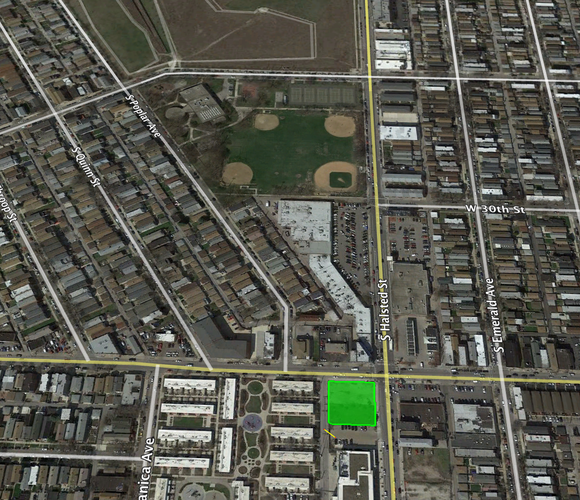

maps created using Google Earth

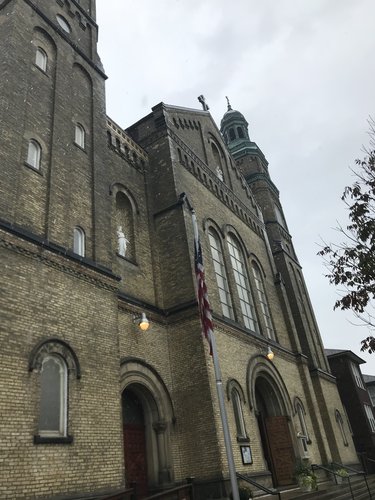

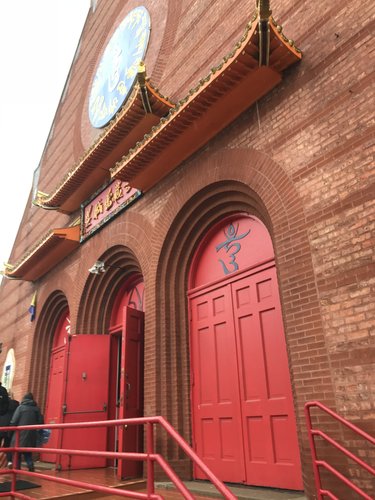

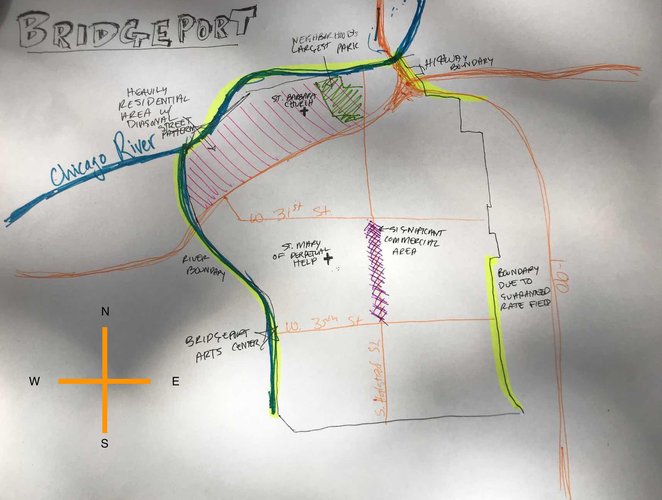

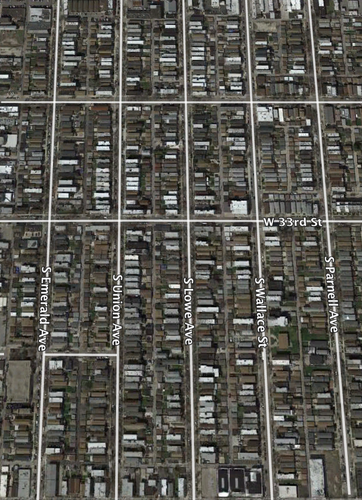

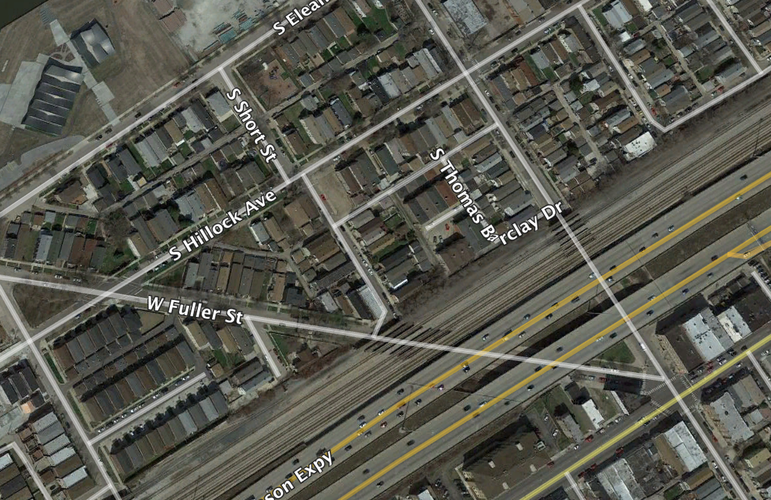

Bridgeport is quite a large neighborhood, and from what I saw of it, it seems to be subdivided into a few smaller sections that overlap and intermingle to a certain extent; there is only a limited sense of overall neighborhood coherence. The main artery of the neighborhood is South Halstead St., which has a variety of small shops and restaurants. Many of the restaurants offer Chinese food, and I noticed a few Mexican restaurants mixed in. Moving north, I encountered an area with a more clear Eastern European influence-- the St. Mary of Perpetual Help Church was founded in 1882 by Polish immigrants, and much of the signage within the chapel is written in Polish. The Eastern European Catholic influence is evident further north as well, as the St. Barbara Church and school, the other major place of worship in the neighborhood, was also founded by Bridgeport’s Polish community, in 1914. As I walked further north and east, Chinese businesses became more common, as did signage in Chinese. Not too far north of the St. Mary of Perpetual Help Church was the Ling Shen Ching Tze Buddhist Temple, which was converted from a church to a temple only 20 years ago. The northwestern region of Bridgeport stands out from the rest of the neighborhood because its streets are positioned at an angle to the standard grid system that prevails in the rest of the area. This makes driving between the two regions more difficult, and it seemed that the houses in the diagonally-organized area were more isolated, with fewer community institutions, pedestrians, and public spaces than in the rest of Bridgeport.

The clearest evidence of a cohesive neighborhood atmosphere was the interactions I saw between people. One of the local coffee shops, Jackalope Coffee, was hosting a block party to celebrate its 5-year anniversary in the neighborhood, and many of the patrons knew each other and were chatting about their lives and families. This was also true of the Bridgeport Coffee House. In addition, there were several stores that incorporated “Bridgeport” into their names, and a customer I saw at Jackalope Coffee was sipping tea from a mug that said “Bridgeport Rocks!” Another significant sign of neighborhood unity was the many clear indications that I was in the heart of Sox territory. Guaranteed Rate Field is located on the eastern border of Bridgeport, and throughout the neighborhood there were signs saying “Go Sox!”, stores selling paraphernalia supporting the team, and people sporting the logo. Throughout the neighborhood, I also noticed signs saying “Bridgeport Community Watch: We call 911”. Combined, these features helped give the otherwise disparate elements of the neighborhood a more cohesive feeling.

In the above diagram, the purple line represents the 11th ward, which is mostly composed of Bridgeport, the blue line represents CPD police districts, the green line represents the U.S. census tracts, and the yellow line represents the boundaries of Bridgeport itself.

Among the first people to live in the community along the South Branch of the Chicago River were traders and fur company workers, as Henry Binford notes in “Multicentered Chicago”. However, the large, diverse, varied neighborhood that today is Bridgeport originated in 1836, when construction began on the Illinois and Michigan Canal, which represents the first true phase in Bridgeport’s expansion. According to the Encyclopedia of Chicago, Bridgeport likely got its name from canal commissioners in order to distinguish it from Canalport, a settlement that had been planned earlier. The first inhabitants of Bridgeport were Irish immigrants who arrived to work on the canal, followed closely by Germans and Norwegians.

The second period of development in Bridgeport came in the mid-19th century, when many of the area’s meatpackers relocated to the Union Stock Yards, and manufacturers began to move to Bridgeport, providing residents with a new source of employment. During this second period, many of Bridgeport’s religious institutions were founded. Most of the Eastern European immigrants who populated the area were Catholic, and they were responsible for the creation of the St. Mary of Perpetual Help Church and St. Barabara Church, two Polish Roman Catholic monuments that dominate the horizon over Bridgeport. The development of parishes in the Catholic tradition within Bridgeport seems to have been a deliberate planning strategy, as Catholic immigrants sought to emulate the neighborhood structure they were familiar with at home.

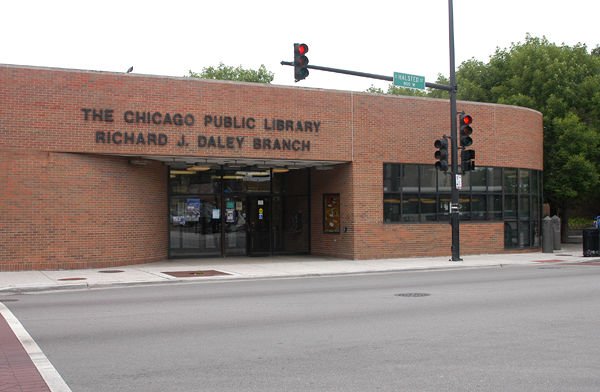

In the 1930s, Bridgeport faced another era of change and redefinition, as Chicago’s famous Democratic machine began to take shape under Mayor Anton Cermack. The role of Bridgeport Democrats in Chicago’s political history is intertwined with Bridgeport’s neighborhood identity. Bridgeport was and still is largely a blue-collar area, and the five Chicago mayors-- Edward Joseph Kelly, Martin Kennelly, Richard J. Daley, Michael Anthony Bilandic, and Richard M. Daley-- who hailed from the neighborhood could all speak to the needs of the city’s working class. Mayor Kelly was a first generation Irish-German American who had worked his way up from working odd jobs around Bridgeport as a child to the mayorship, and could relate to the interests of the city’s many Irish and Eastern European immigrants. Richard J. Daley, perhaps Chicago’s most famous mayor, spent a great deal of time working in Bridgeport’s Eleventh Ward as a young man, and remained living in Bridgeport even as his career soared. In return for serving as the breeding ground for five of Chicago’s mayors, Bridgeport gained further economic stability.

The last phase of the development of Bridgeport is the modern era. In recent decades it has seen an influx of Mexican-American and Chinese-American inhabitants, through the expansion of Chinatown to the northeast and Pilsen to the northwest. With them have come distinctive restaurants and schools and afterschool programs dedicated specifically to children of those communities. Like many of Chicago’s neighborhoods, Bridgeport is also beginning to transition into a neighborhood for young hipsters, although it still retains some of its blue-collar roots. The low cost of living in the neighborhood, its nearness to both Chinatown and downtown, and its working-class political history have enticed young people to the neighborhood, and led them to found trendy institutions like Maria’s Packaged Goods and Community Bar, Jackalope Coffee & Tea House, the Co-Prosperity Sphere (an experimental cultural center), and the Bridgeport Art Center, among others.

It seems that the greatest factors driving the development of Bridgeport over the years were first the construction of the Illinois and Michigan Canal, and subsequently the movement of various manufacturers into the area. These two factors-- transportation and economic development-- are the elements that Ann Durkin Keating emphasized in Chicagoland: City and Suburbs in the Railroad Age, saying that first the canal and then the Union Stock Yards played a major role in the population and development of Bridgeport and nearby Back of the Yards. Urban planning seemed to play a limited role in Bridgeport’s history, but neither does it fit with Reginald R. Isaac’s conception of an area where people simply reside rather than live, work, shop, play, recreate, and pray. All that is necessary for these activities is contained within Bridgeport. What started as a fur trader encampment has developed into one of chicago’s largest, most diverse up-and-coming neighborhoods.

Sources

https://stbarbarachicago.org/history/

http://lockzero.org.uic.edu/V.html,

Keating, Ann Durkin. 2005. “Chapter Four: Industrial Towns of the Railroad Age”. In Chicagoland: City and Suburbs in the Railroad Age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Isaacs, Reginald R. “The Neighborhood Theory: An Analysis of Its Adequacy.” Journal of the American Institute of Planners 14, no. 2 (1948)

http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/165.html

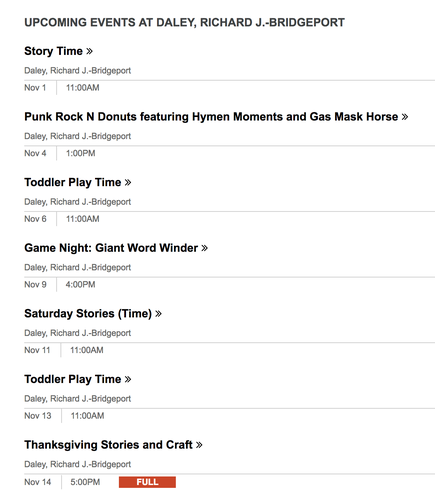

Social Mix

© Social Explorer 2005-2017

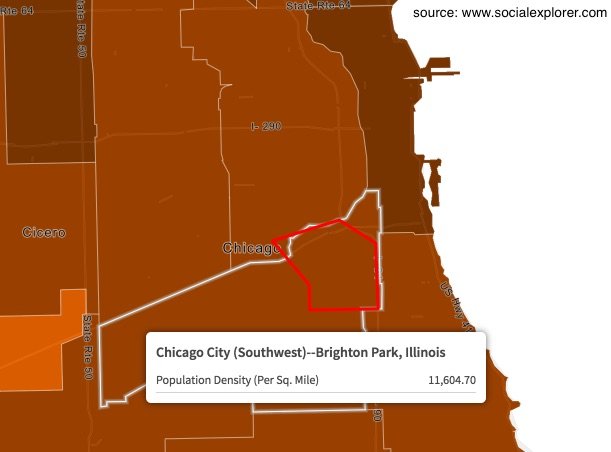

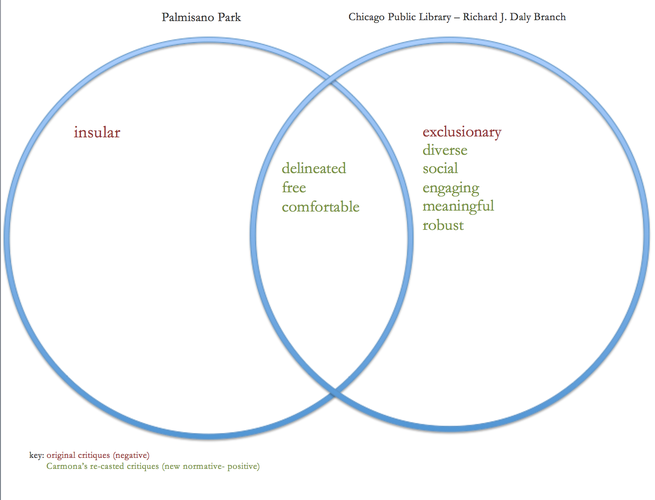

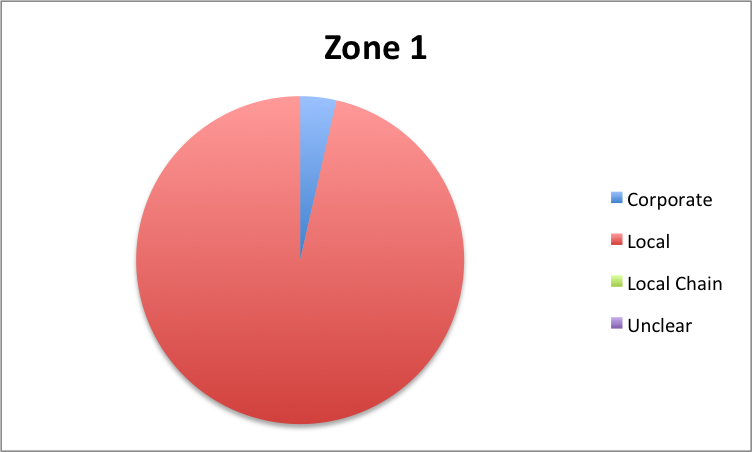

Based on the indices I calculated above, Bridgeport is fairly diverse. Although Bridgeport is its own community area and it is therefore difficult to compare it to other areas in its immediate vicinity, it is significantly more diverse in all three categories than its broader region. However, Bridgeport is slightly less diverse than the city of Chicago as a whole. Chicago is more diverse in all three measures, and especially so in educational attainment. This may be explained by the fairly large number of universities and colleges in Chicago, fewer of which are located in Bridgeport or the Southwest Region, as they tend to cluster downtown and along Lake Michigan.

It is important to note that I made some adjustments to the data groupings in order to keep the number of categories at five or fewer. For the racial index, I grouped Hispanic/LatinX people of all races together and took the numbers for the other races from the non-Hispanic/LatinX category. This left me with six categories; I removed the numbers for Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders because in the samples I studied their population was so small as to make up effectively 0% of the total population. People of mixed race or who listed their race as “other” are also not included. The income category is divided evenly into four large income brackets. The educational attainment category groups those with a master’s, professional degree, or doctorate together into one category.