Overview

Size [1]

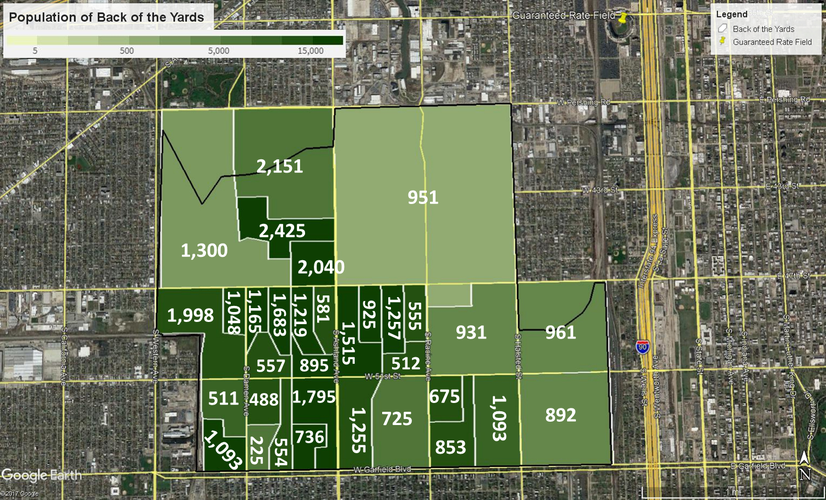

Total Population: 62,010 (about 12 Perry neighborhoods put together!)

Population Density: Approximately 7993.2 people per square mile

Physical Area: ~2491 acres

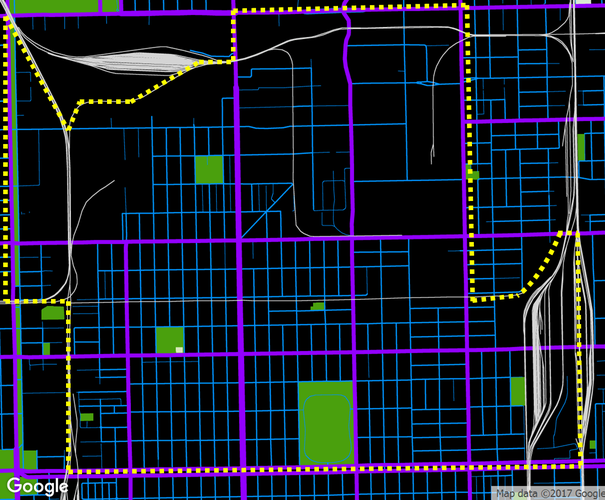

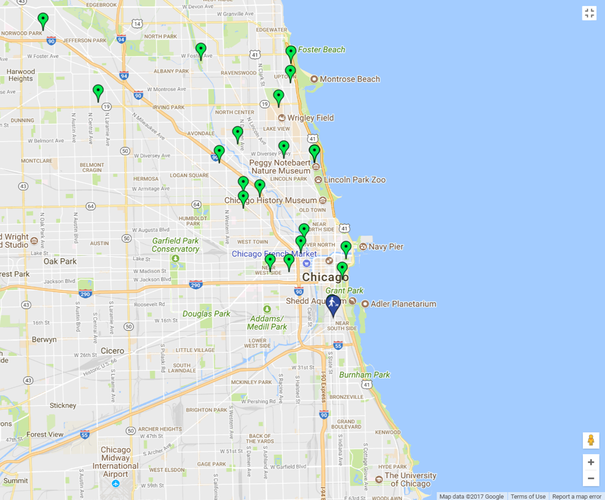

In the map below, the green scale indicates the population density per square mile of each census block tract. The total population of the block tract is shown in white.

Identity

The Back of the Yards neighborhood absolutely displays a coherence and sense of community pride. Several shops sell Back of the Yards t-shirts and baseball caps in both English and Spanish, and many businesses and shopping centers include Back of the Yards in their names. The Union Stock Yard Gates remain a neighborhood identifier. However, Back of the Yards is quite a large area. While the gates are a distinct feature, then, the name of the neighborhood itself seems to serve more strongly as a badge-of-honor bond amongst residents. Banners on street lights along the main commercial street also identified the neighborhood. People do seem to be tied to their face-block neighborhoods, but there is a true sense of pride around belonging to Back of the Yards. Most of Back of the Yards’ borders are large streets, which limit pedestrian traffic and logically demark the area.

One unique thing about Back of the Yards is that it has a neighborhood song! I did not have the opportunity to interview residents to discover whether it was still commonly known, but I hope to on my next visit. What I did observe was a sense of community with the larger Chicago City neighborhood. I found a large mural on the side of Hedges Elementary School depicting Chicago landmarks (e.g. the Sears tower and the Bean) and advertisements for the One Chicago reading program.

The cultural identity is clearly influenced by the Hispanic immigrant subpopulation that constitutes the majority of the neighborhood’s total population. Many signs and advertisements are in both Spanish and English. Money sending services, immigration attorneys, and passport photo services were very common, as were people with pull-carts selling tamales and other traditional street foods. Other cultural features include a school named after César Chavez and specialty ethnic grocery stores, bakeries, and liquor stores.

Community-sourced efforts, such as this Little Free Library, offer bilingual resources, as do larger corporations in the area. The cultural identity of Back of the Yards is thereby quite clear.

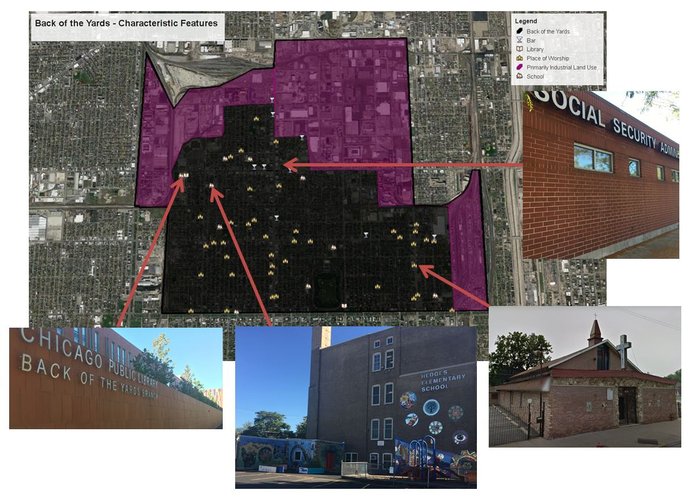

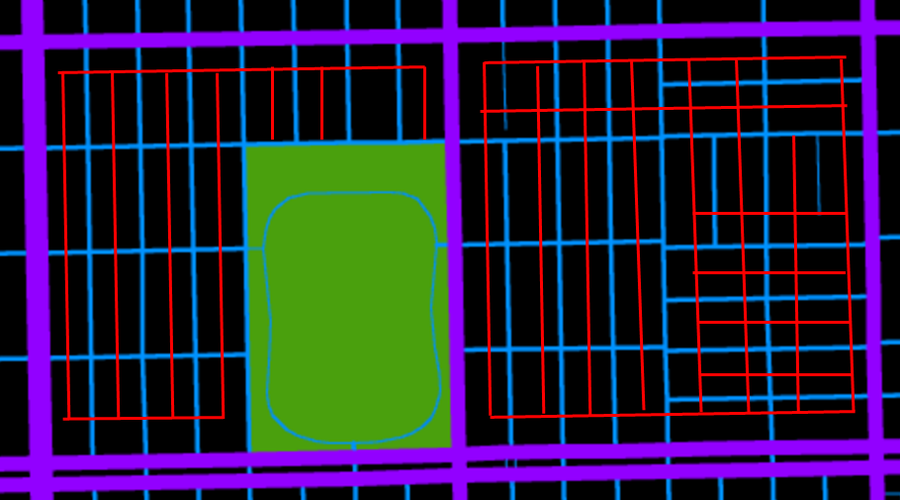

Character Diagram

Back of the Yards has many churches, two public libraries, and access to several governmental service centers.

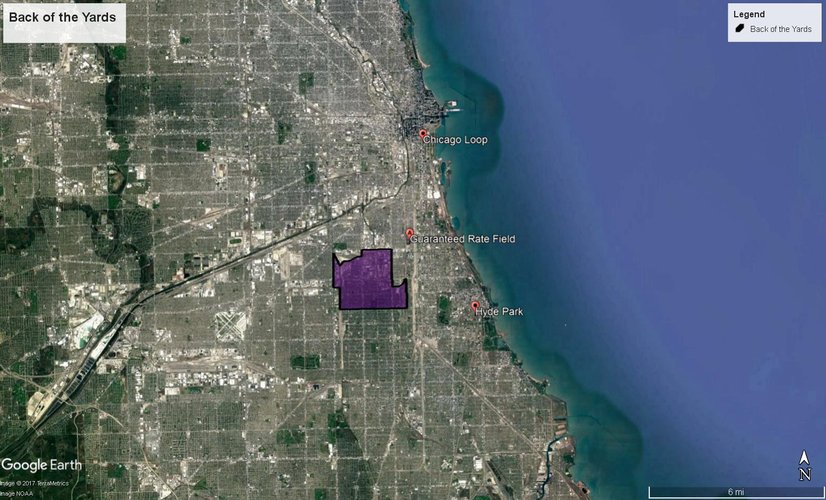

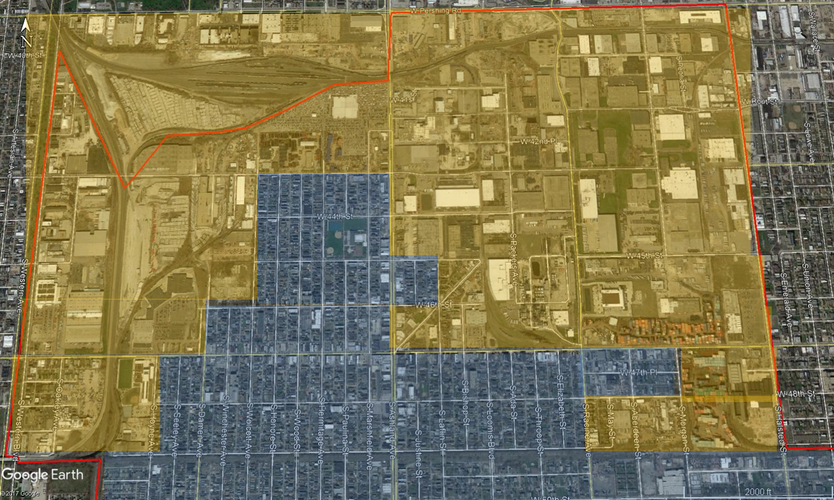

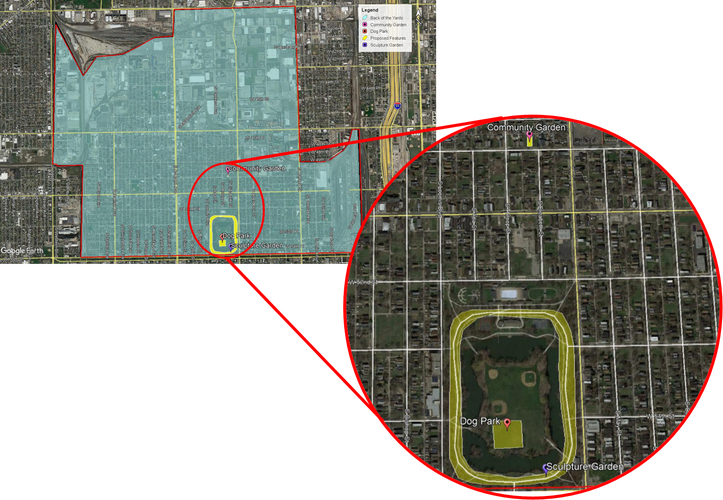

Overlapping Geographic Definitions

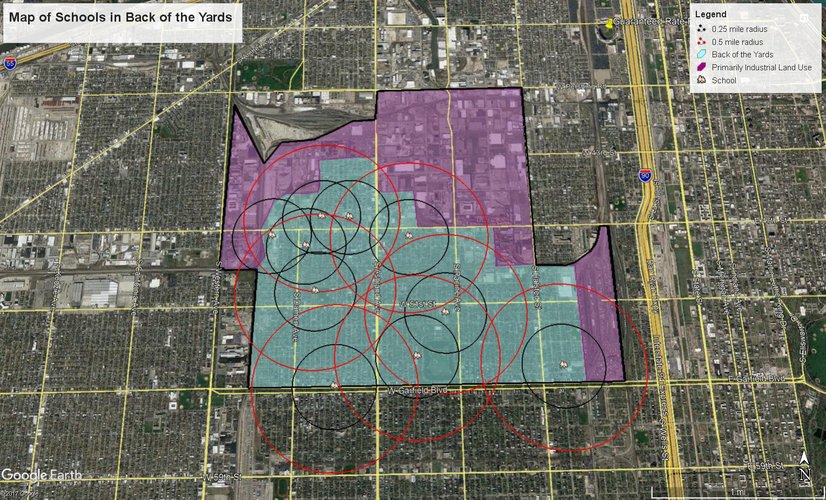

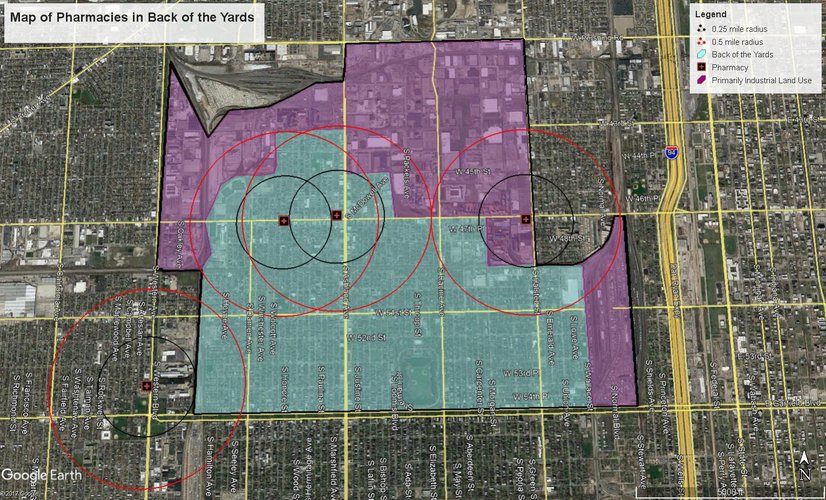

The following map displays amenities available in Back of the Yards, including libraries, public transit, elementary schools, and fire departments.

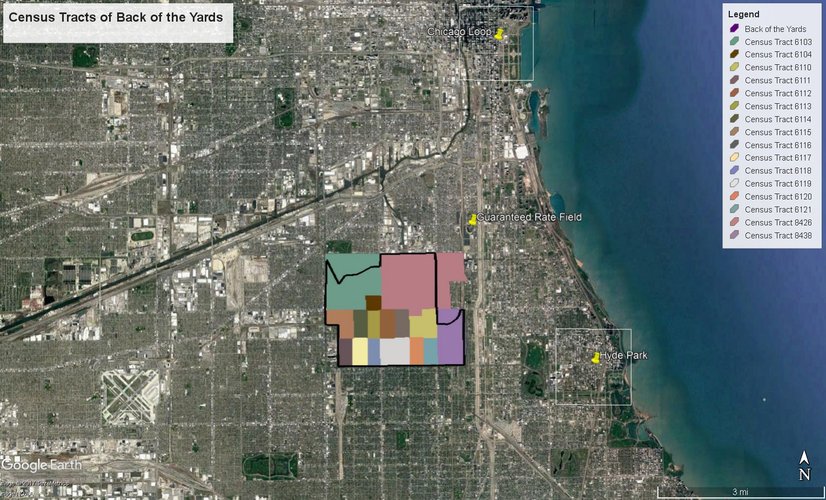

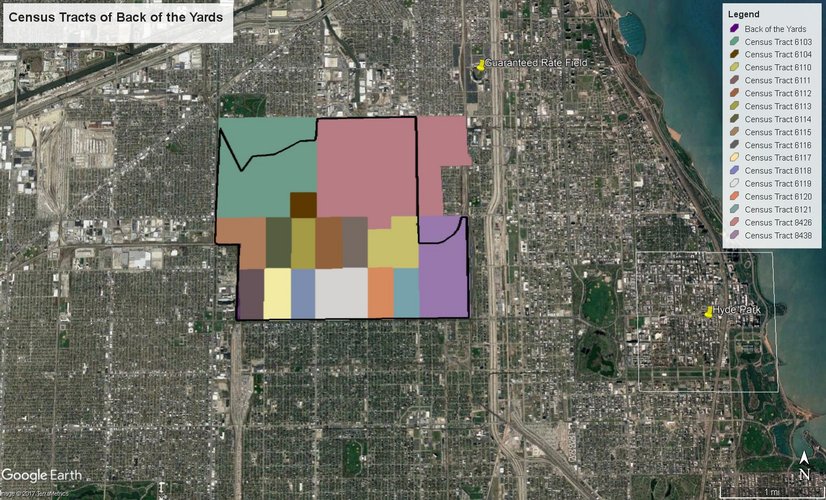

Back of the Yards is divided into 16 census tracts, mapped below.

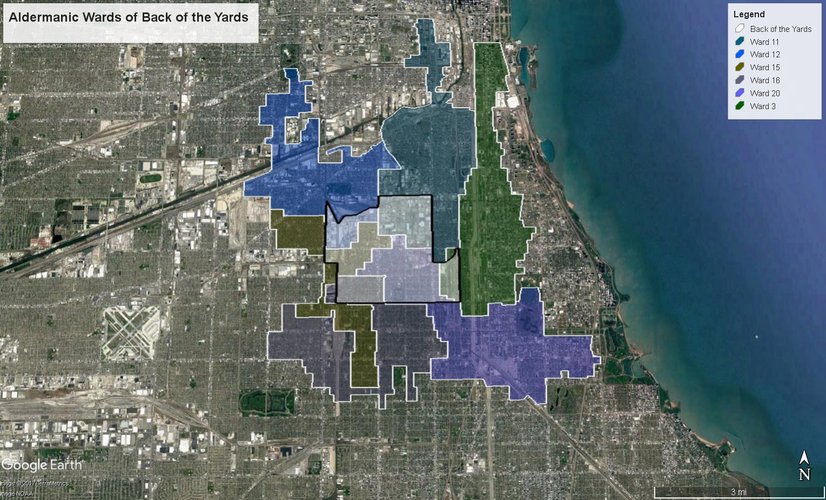

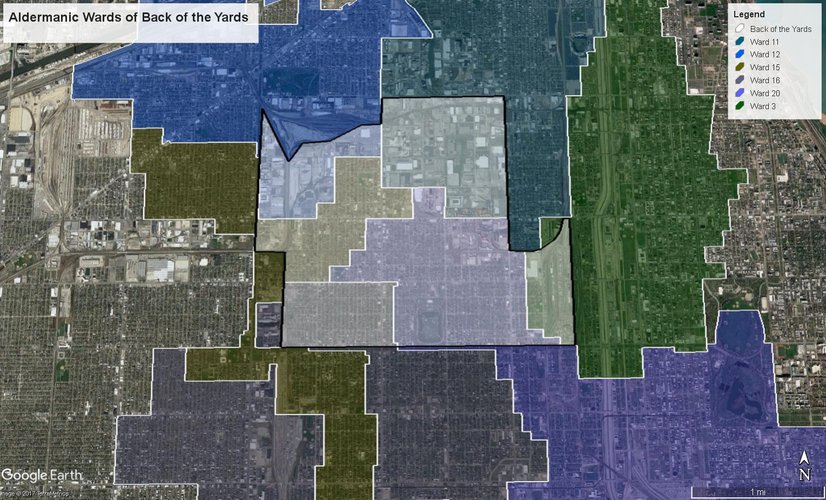

Here we see that Back of the Yards is represented by six different Aldermen.

History

Back of the Yards became a part of what is now the New City community area of Chicago when it was annexed from the town of Lake in 1889. By this time, it was already a sprawling neighborhood with a large meatpacking economy thanks to the railroads, Union Stock Yard, and “perfection of the refrigerated boxcar”[2]. Irish and German butchers originally settled in Back of the Yards, and were later joined by Czechs, Slovaks, Poles, and Lithuanians[3]. Each ethnic enclave had its own parish and school, “with a head priest imported from the motherland as a way to stay connected to their heritage”[4]. Every group also tended to have separate social and cultural organizations, including men’s social clubs, women’s leagues, and sports associations[5]. The strong majority of workers lived in Samuel Gross’ cheap workingmen’s cottages near the factories[6]. 25,000 people were employed in packing and slaughtering houses by 1900, with a thousand more working in other neighborhood factories that utilized the byproducts of meat processing[7]. The butchering process was broken down in a disassembly line fashion. This was significant in that it created entry-level work for the thousands of European immigrants entering Chicago[8].

Small numbers of Mexican and African American immigrants are recorded moving into Back of the Yards, particularly from Bridgeport, with the onset of World War I and the resultant job openings[9]. However, the area experienced a decline when large shipping trucks began to replace railroads after World War II[10]. Back of the Yards was “a notorious slum”[11]. Jane Jacobs reports that as late as the 1930’s, people from Back of the Yards would provide false addresses when applying for jobs outside of the neighborhood “to avoid the discrimination that then attached to residence there”[12]. The community remained largely Slavic until the Central Manufacturing District closed the stockyards in 1971[13]. Then, the area slowly became a Chicano community with a minority African American population[14].

The Great Depression and credit blacklisting forced the many different ethnic groups of Back of the Yards to unify. In fact, it was this unification that allowed the community to “unslum” itself from the portrait of “the dregs of city life and human exploitation” in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle[15]. The Packinghouse Workers Organizing Committee (later known as the United Packinghouse Worders of America, or UPWA-CIO) and Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (BYNC) were established for this purpose in 1937 and 1939, respectively[16]. The UPWA-CIO “raised wages, stabilized employment, and fought for civil rights in the plants”[17]. The BYNC began as a coalition of neighborhood schools, churches, and social clubs across the ethnic enclaves. Uniting the neighborhood as a whole to effect change remains the BYNC’s goal, and the BYNC maintains to this day the slogan, “We, the people, will work out our own destiny”[18]. It operates essentially as a neighborhood-specific government in the Back of the Yards today, with a legislature of 200 elected representatives that sets neighborhood policies[19]. These groups are credited by Jane Jacobs as improving community conditions so that residents wanted to stay rather than immigrate to the suburbs.

The challenge for those staying, however, was that Back of the Yards was blacklisted for mortgage credit and it was therefore nearly impossible to improve one’s quality of living[20]. A survey by the BYNC discovered that Back of the Yards businesses, residents, and institutions had deposits in roughly thirty of Chicago’s savings and loans associations and banks. The neighbors agreed to withdraw their deposits if lending institutions continued to blacklist their district, and so a meeting was held with the lenders to negotiate Back of the Yards’ ability to take out loans. BYNC managed not only to garner favorable consideration of loan requests, but also to receive a loan of $90,000 to modernize and rehabilitate existing dwellings and build new housing[21]. Since this revitalization, Back of the Yards has continued unslumming.

[1] “US Demography 1790 to Present.” Social Explorer, 2017, www.socialexplorer.com/a9676d974c/explore.

[2] “Back of the Yards,” 2004, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/99.html.

[3] Ibid.

[4] “BYNC | About Us | History,” 2017, http://www.bync.org/about-us/history#.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Back of the Yards.”

[7] Ann Durkin Keating, “Chicagoland: City and Suburbs in the Railroad Age” (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2005).

[8] Ibid.

[9] “Back of the Yards.”

[10] Keating, “Chicagoland: City and Suburbs in the Railroad Age.”

[11] Jane Jacobs, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” 2004.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Keating, “Chicagoland: City and Suburbs in the Railroad Age.”

[14] “Back of the Yards.”

[15] Jacobs, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities.”

[16] “Back of the Yards.”

[17] Ibid.

[18] “BYNC | About Us | History,” 2017, http://www.bync.org/about-us/history#; “BYNC | About Us | Hours and Location,” 2017.

[19] Jacobs, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities.”

[20] Ibid.

[21] Jane Jacobs, “The Death and Life of Great American Cities,” 2004.

Social Mix

Diversity Analysis

The Back of the Yards is a southwestern Chicago neighborhood conversationally described as predominately Mexican-American, and of low socioeconomic status. Data provided by Social Explorer, an online demographic database, confirms that Back of the Yards is nearly two-thirds Hispanic. It also shows that less than a quarter of Back of the Yards residents has attended college or other professional training programs. The strong majority (i.e. 70.33%) of households reports an income of $49,999 or less, and 62.37% of occupied housing is rented. That is to say, the everyday consensus is largely correct in its description of Back of the Yards. The Simpson Diversity Index Values of Back of the Yards are very similar to those of its larger community area, New City, because New City is composed only of Back of the Yards and the much smaller neighborhood of Canaryville. Thus, comparing these values provides little context by which the diversity of Back of the Yards may be evaluated.

However, the Simpson Diversity Index Values of household income and household type in Back of the Yards are fairly different from those of the Chicago and its southwestern region to which Back of the Yards belongs. Back of the Yards demonstrates less diversity in household income than these two greater areas, likely correlated with its below average educational achievements. Household type was described as either a married-couple family, a family with male householder without a wife, a family with a female householder without a husband, or a nonfamily. Here, Back of the Yards demonstrated significantly greater diversity than the rest of southwestern Chicago and Chicago as a whole. Southwestern Chicago had a lower proportion of families with single male householders, and Chicago at large had both a much high proportion of nonfamilies and much lower proportions of single parent families. These proportional differences between Back of the Yards and Chicago likely correlate with the socioeconomic status diversity of the city. Another likely factor is the number of college students located near the many colleges and universities outside of Back of the Yards, as students are less likely to have started families. The Simpson Index Values for age and sex demonstrated less variation across areas. This indicates that Back of the Yards is fairly representative of the rest of southwestern Chicago and Chicago as a whole in terms of age and sex diversity.