Overview

Size

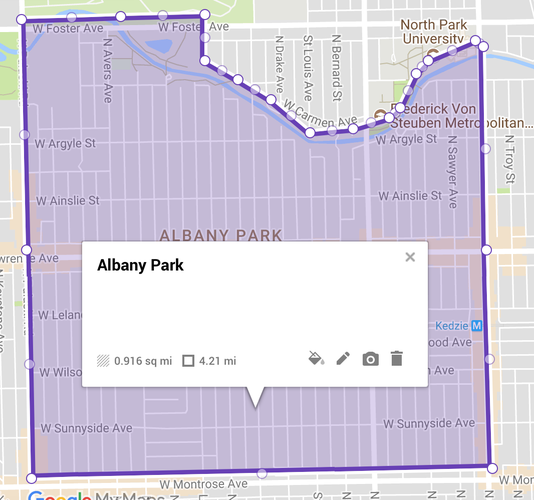

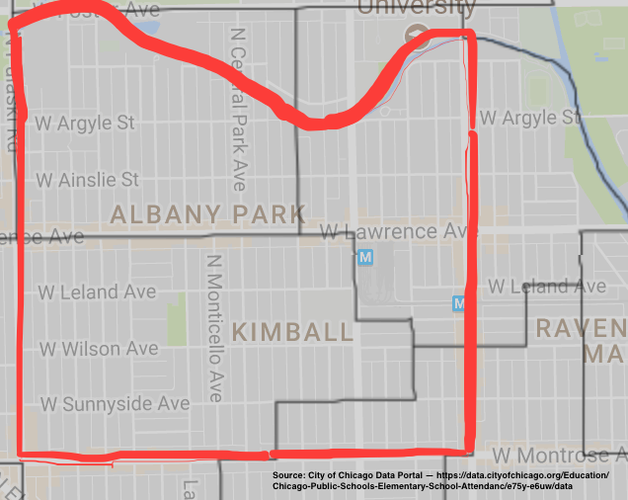

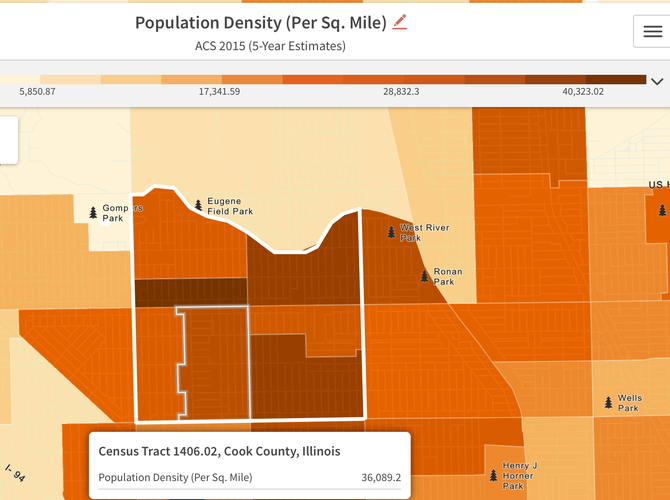

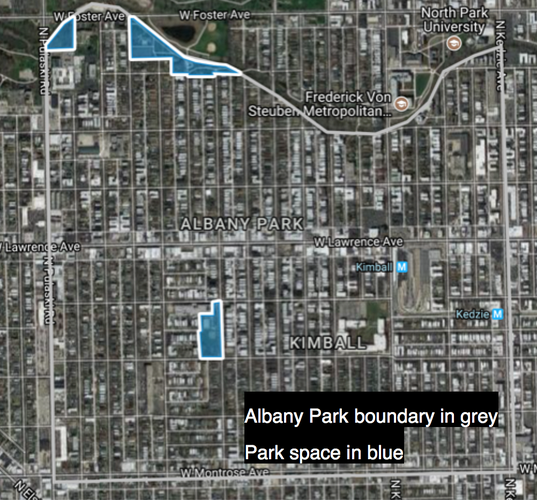

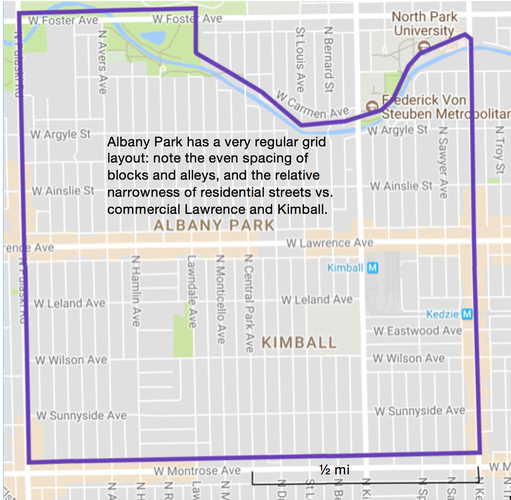

Albany Park is approximately 0.93 miles square, or 595 acres (1), with a population of around 30,109 residents (2). The neighborhood contains multiple elementary schools, indicating it is larger than Perry's ideal neighborhood size of one elementary school. It contains about 2/3 the area and only 1/3 the population of Jacobs' districts.

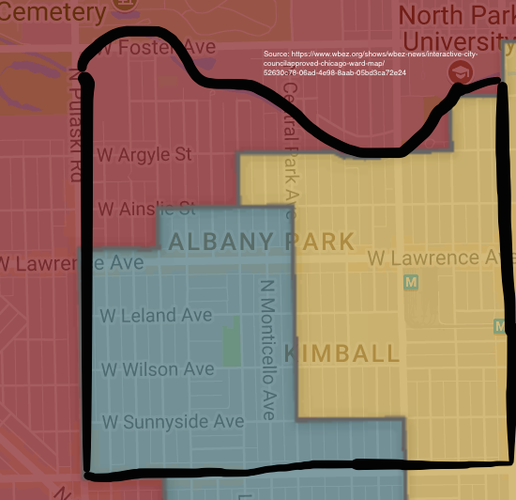

Layers

Identity

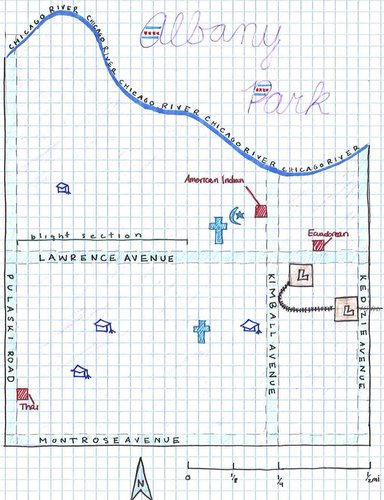

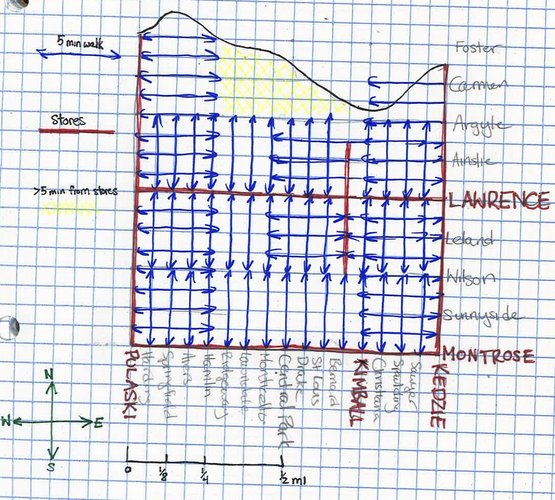

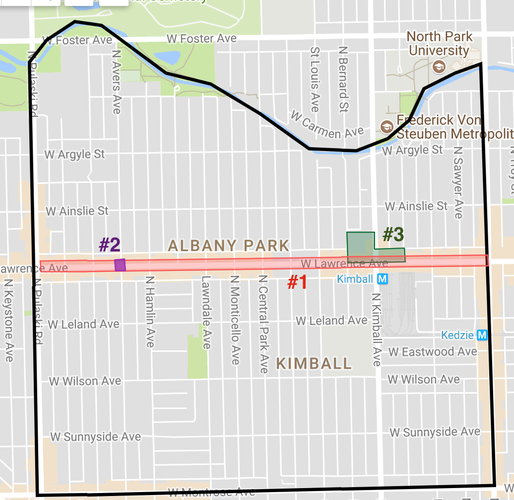

Albany Park’s main commercial thoroughfares give off a strong sense of definition. Lawrence Avenue, the main commercial drag (between Pulaski Drive and Kedzie Avenue), contains a profusion of small businesses packed tightly together. They do not give off the impression of belonging to a particular ethnic neighborhood, but they indicate the importance of ethnic heritage to Albany Park’s residents: Korean, Mexican, Ecuadorian, Yemeni, Chinese, Indian, Pakistani, Thai, and Serbian Americans are represented in the businesses and institutions of the neighborhood, among others. The common feature nearly all the shops share with each other is that the owner’s national origin features prominently in the store’s name, décor, or offerings. This trend extends beyond businesses that normally cater to specific ethnicities, like grocery stores or pharmacies: even hair salons and electronics stores have foreign flags out front. Notably, Lawrence Avenue also contains several businesses and centers providing immigration services. The character of Albany Park’s business community reveals perhaps the two most essential defining characteristics of the neighborhood: its multi-ethnic population and its role as a haven for immigrants.

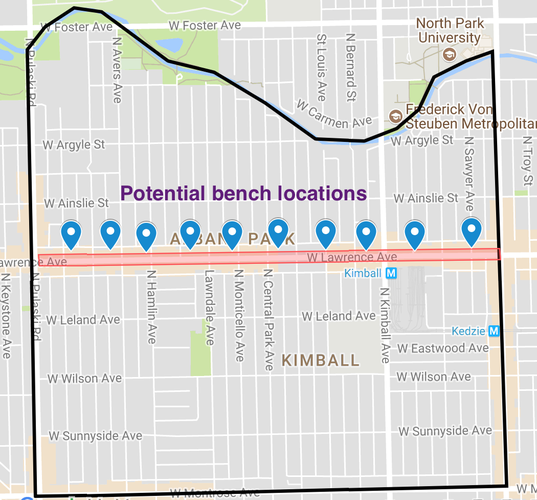

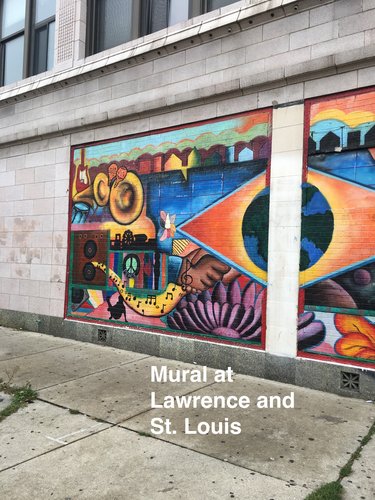

Local business names and public facilities provide a good idea of the neighborhood’s boundaries as well. From The Albany Park Bank & Trust (“Albank”) to the Albany Park Fresh Market to the Albany Square Outlet Mall, Lawrence Avenue abounds with businesses named for the neighborhood. A mural depicting some of the transit that runs through the neighborhood as well as a variety of musical traditions can be found on Lawrence and Saint Louis. The Albany Park Community Center is only a block north on Ainslie Street. West of Pulaski Avenue, however, most businesses bear the name “Mayfair” rather than Albany Park, indicating a sharp boundary. This divide also appears in the nature of the businesses themselves; while the businesses east of Pulaski are almost exclusively local, big-box stores populate most of the business space west of Pulaski. Street names also provide a clue: Lawrence Avenue is officially nicknamed “Seoul Drive” from Pulaski to Kedzie, and several streets within the neighborhood have been named after locally important people.

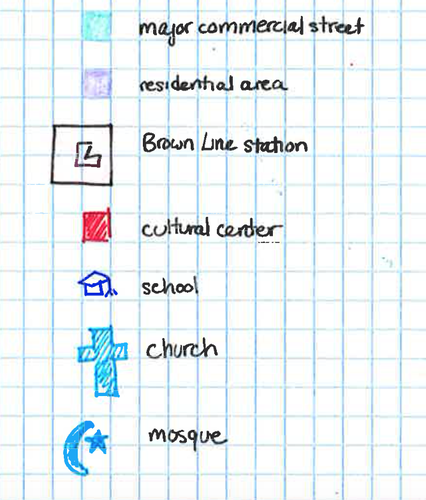

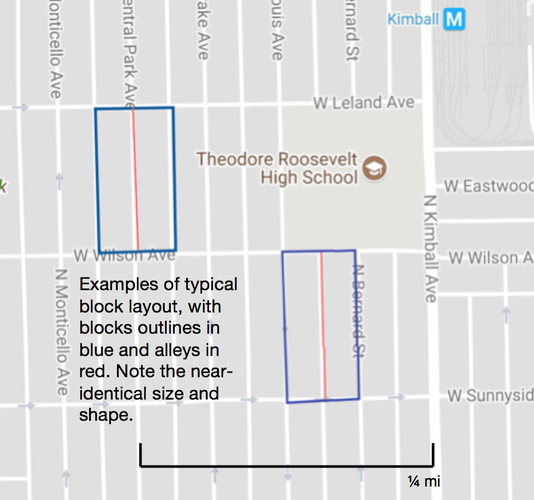

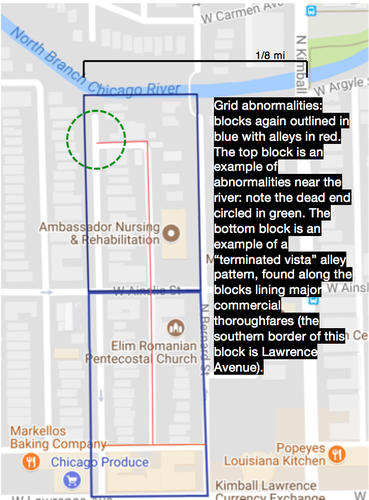

Diagram

History

Albany Park’s raison d’être has always been its transportation connections. Its first settlers were farmers, mainly of German and Swedish descent; as Chicago’s population boomed in the later decades of the 19th century, it gained popularity as a suburban community. The area was absorbed into the City of Chicago with the 1889 annexation of Jefferson Township, of which is was a part. What really set off the neighborhood’s development, however, was a large land purchase by a group of investors in 1893. These investors, who gave the neighborhood the name Albany Park after the city of Albany, New York, brought streetcar lines to the area. Fourteen years later, the Ravenswood Elevated Line (now the Brown Line) was extended to Kimball, and the retail corridor along Lawrence Avenue exploded due to the increased traffic. The easy transit connection to downtown that the El provided also spurred residential development. The Brown Line still serves as a major lifeline to the neighborhood, and Lawrence Avenue remains Albany Park’s economic and social heart.

The development of the Albany Park neighborhood that followed the advent of the El appears to be the dominant push in shaping the local built environment. The residential areas contain the bungalows and red- and yellow-brick three-flat apartments common to this period of development in Chicago; some homes also show the influence of the Prairie Style. Many commercial buildings, particularly along Lawrence, feature Art Deco-style embellishments, and the buildings whose dates of construction are carved into the stone were mainly built in the 1910s and 1920s. While the primary residents of Albany Park in its early decades were Northern European immigrants, its population in the post-El years through the Second World War were mainly Russian and Eastern European Jews expanding from the slums of the Near West Side. The Jewish residents of this second chapter in Albany Park’s history built up the neighborhood densely, and their exodus to the suburbs in the late 1950s along with much of Chicago’s Jewish population seriously hurt the area.

The neighborhood reached its nadir in the late 1970s both in terms of economy and population. The most jarring sign of its decline was the increase in storefront vacancies along Lawrence Avenue, the street that best serves as a bellwether for the neighborhood’s health. Redevelopment efforts sponsored by the city came in 1978, and through the 1980s and 1990s Albany Park experienced a renaissance. In this third chapter Albany Park welcomed immigrants from East and Southeast Asia, the Middle East, South Asia, and all over Latin America. Most influential were the Korean immigrants, who spurred much of the economic redevelopment. Though some of the Korean population has since moved to the suburbs, the neighborhood has a strong Korean presence, and their role in reviving Albany Park is reflected in an officially designated nickname for the stretch of Lawrence between Kedzie and Pulaski: “Seoul Drive”. Traces of the neighborhood’s old inhabitants remain, however, in the buildings and place names. A Pentecostal church on Ainslie and Bernard, for example, occupies a building that was clearly once a synagogue called Beth Israel. Albany Park’s proximity to transportation and large variety of housing options have made it an attractive choice for new immigrants from various corners of the world throughout its history.

Sources:

· Encyclopedia of Chicago, “Albany Park.” http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/36.html

· WBEZ, “Albany Park, Past and Present.” https://www.wbez.org/shows/wbez-blogs/albany-park-past-and-present/da30b2d1-6cc2-4a46-8b40-d42d82b8797f

Social Mix